WASHINGTON -- Eight years ago this week, I launched a new blog on political polling with a post on party identification. At the time, many Democrats were up in arms over survey samples that seemed too Republican and were contending that if pollsters would adjust for the "apparent overrepresentation" of Republicans in their samples, Sen. John Kerry would be running a closer race against President George W. Bush.

Two presidential elections later, the argument over the partisan makeup of poll samples continues, only this time the roles are reversed. Now it's Republicans and conservative pundits railing against allegedly "skewed polls." This year's controversy has one new dimension: a website devoted to recalculating poll results to match a partisan composition more favorable to the Republicans (as well as the inevitable parody Twitter feed).

This year's critics would do well to revisit the lessons of 2004.

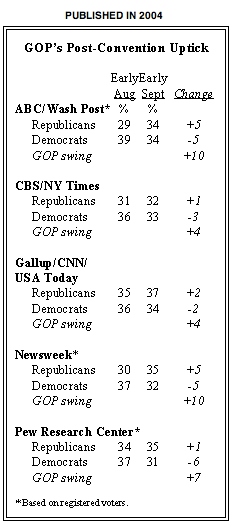

Then as now, an incumbent president saw a boost in his poll numbers following the party conventions, which coincided with a shift in party identification as measured by most national polls. On the same day I launched my blog, the Pew Research Center published a roundup of the changes in party identification on five major polls, all of which showed a net shift in the Republican direction.

The average of the five polls from August 2004 had given Democrats a five percentage point advantage (37 to 32 percent) in party identification, but a month later Republicans were enjoying an average two-point edge (35 to 33 percent). Democratic critics voiced strong skepticism. A Republican edge ran counter to exit polls from prior elections and decades of previous surveys. The partisan composition of the electorate could not possibly change that much in such a short time, they argued.

But when President Bush won the election narrowly in November 2004, the final exit poll showed an even division of Democrats and Republicans (37 percent each). The party composition that the critics had deemed impossible had come to pass.

The apparent shift in party identification in the wake of the 2012 conventions has been relatively modest, no more than a percentage point or two toward the Democrats in the adult sample results reported by national polls. This year's controversy has focused more on various state-level polls whose composition too closely represents the party composition of the 2008 electorate, according to the critics.

This focus on party identification is as misguided as it was eight years ago. Here are five tips to avoid some common misconceptions at the heart of the controversy.

1. Party identification is an attitude, not a demographic characteristic. "Generally speaking, do you consider yourself a Republican, a Democrat, an independent or what" is basically the question most pollsters ask. People can change their minds about which party they consider themselves closer to. They cannot change their age, gender or race (at least not easily).

2. Party identification does not equal party registration. Many (but not all) states ask voters to affiliate with a party when they register to vote, usually to enable voting in party primary elections, and most of those states publish statistics on the number of Democrats and Republicans.

As Nate Cohn of The New Republic has noted, however, this week's much-criticized Florida survey conducted by CBS News, The New York Times and Quinnipiac University asked questions about both and, not surprisingly, found much inconsistency. Specifically, the poll found twice as many voters who said they consider themselves independent or part of a third party (36 percent) as voters who said they were registered with no affiliation to the Democratic or Republican parties (18 percent). Notably, registered Republicans were a little more likely than registered Democrats to report an independent identification.

3. Party identification can change slightly during a presidential campaign, as the 2004 experience demonstrates. Although the vast majority of voters have a sense of party identification that rarely alters, some voters -- particularly those who just "lean" to one of the parties -- may shift back and forth between categories depending on recent events. When pollsters ask the party ID question and the context in which they ask it can also affect the answers.

4. Claims that media polls "assume" a specific partisan or demographic composition of the electorate are mostly false. The pollsters behind most of the national media surveys, including those who conduct the CBS/New York Times/Quinnipiac, NBC/Wall Street Journal/Marist and Washington Post polls, all use the same general approach: They do not directly set the partisan or demographic composition of their likely voter samples. They first sample adults in each state, weighting the demographics of the full adult sample (for characteristics such as gender, age, race and education) to match U.S. Census estimates for the full population. They then select "likely voters" based on questions answered by the respondents, without making any further adjustments to the sample's demographics or partisanship.

There are pollsters that weight the subset of "likely voters" by party or to match very specific assumptions about the demographics of those they expect to vote. However, such practices are generally shunned by the national media surveys whose recent results have drawn most of the "skewed poll" criticism.

5. Weighting a new survey to match the party ID results of an old exit poll is a bad idea; "unskewing" polls by weighting to Rasmussen Reports' party ID results is even worse. Exit polls provide a helpful guide to the composition of past electorates, but have their own potential for random error and, as recent experience shows, sometimes make for poor predictors of the future.

But if weighting current surveys to match past exit polls is a bad idea, the new idea of 2012 -- "unskewing" polls by reweighting their results to match the party results produced by the Rasmussen polls -- is galactically stupid.

Rasmussen does report party affiliation results for its adult samples, but it asks a very different question and asks it using an automated, recorded voice -- rather than live interviewers. Moreover, some believe Rasmussen's method reaches a less-than-representative sample of adults.

Put the debate over Rasmussen's methodology aside, however. Even Scott Rasmussen thinks weighting other surveys to his measurements is a bad idea. "Different firms ask about partisan affiliation in different ways," he told BuzzFeed. "You cannot compare partisan weighting from one polling firm to another."

There is room for a reasoned debate over the demographics of the likely electorate. Jay Cost of the Daily Standard is right to argue that while pollsters may not impose their assumptions about who will vote directly, "the myriad of choices they make about when to poll, whom to poll, and how to poll" ultimately determine the composition of their samples. And since those choices remain as much art as science, skeptical scrutiny is appropriate.

It's also fair to ask if shortcomings in those methods may be exaggerating the recent shifts to the Democrats. Something like that may have happened at this point in the 2010 campaign. The big enthusiasm gap two years ago did foretell a GOP turnout advantage, but some polls found a consistently larger Republican surge in their results than actually transpired.

Yet that parallel alone amounts to bad news for Republicans. Few would have guessed just a few months ago that 2012's polling controversy would boil down to the way pollsters are dealing with a surge in Democratic voter enthusiasm in September.