This article originally ran in NEED Magazine.

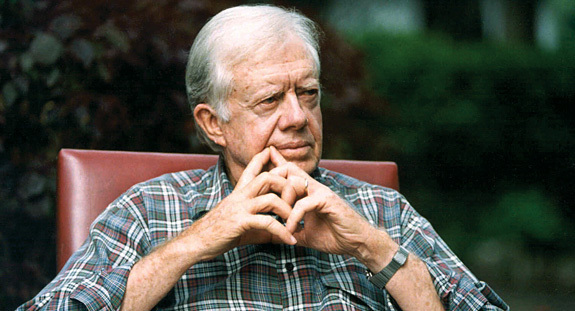

FORMER US PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER IN SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA IN 1997. PHOTO | ROBERT GROSSMAN/THE CARTER CENTER

"In every case when I thought I was doing somebody else a favor by building a house or something like that, I found that I got a lot more out of it than I put into it."

Q: President Carter, what initially inspired you to become involved in humanitarian issues?

A: When I became a state senator, then later governor and ultimately president, I realized that all public officials have a great responsibility and duty to analyze the needs of the people that they have been elected to serve.

When I was a state senator, we were still in the midst of 100 years of racial segregation in this country, based on the fact that we were supposed to have separate but equal facilities. I saw in my own early life the need for equality of treatment between black and white American citizens; that was the first introduction I had to alleviating suffering and discrimination and giving people some hope that their lives would be equal to others as citizens of this country.

Q: One of the themes that emerges throughout the work associated with the Carter Center is hope. Why should people be hopeful in regards to humanitarian assistance, peace and human rights?

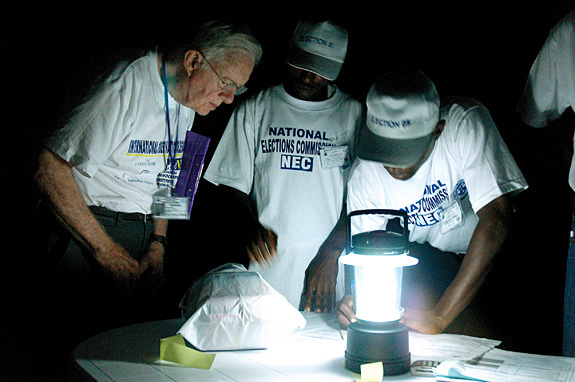

A: First of all, we have to be aware of what's going on in the rest of the world. You know we just finished helping with an election in Liberia. It's very disturbing to know that over half of the people in Liberia are living on less than 50 cents a day, and over half the people in the whole world live on less than two dollars a day. That's almost inconceivable to rich, prosperous, safe and satisfied Americans. If you just stop for a few minutes and think how [you] would survive if [you] only had that much money to pay for a place to live and to pay for food and clothing, you can see that there's nothing left over for health care, education, self-respect or hope that the future will be better than you've already known it. The absence of opportunities [along with] human suffering, persecution, being in the midst of war and suffering from unnecessary diseases [are] all factors [that] eliminate hope among many people in the world, and to give them a better opportunity provides hope.

PHOTO CAPTION: PRESIDENT CARTER LOOKS AS ELECTION OFFICIALS BEGIN THE VOTE-COUNTING PROCESS DURING LIBERIA'S PRESIDENTIAL AND LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS IN OCTOBER 2005. PHOTO | DEBORAH HAKES/TCC

Q: Within the realm of humanitarianism, is there one issue or project that really inspires you?

A: There are a lot of them. The Carter Center has programs in 65 nations, and 35 of those countries are in Africa. We deal with diseases that have been completely eliminated in all of the industrialized world. These are diseases, though, that still afflict millions and millions of people. So we go into local villages in the jungle or in the desert areas in Africa and sometimes in Latin America and try to alleviate this suffering. To see the dramatic transformation that takes place in the lives of those people when they never have to suffer from a terrible and preventable disease is the type of thing that really inspires me.

For instance, we began working on a disease called dracunculiasis or Guinea worm a number of years ago. We found 3.5 million cases in over 23,000 villages in more [than] 20 nations. We've been in all those villages now and taught the people what causes the disease and how to prevent it. We've reduced the number of Guinea worm cases in the world by more than 99.7 percent. We still have .3 percent of those original cases primarily in Ghana and southern Sudan, which have been afflicted with wars. This is the kind of experience that we've had that has been inspirational to me.

I would say that the biggest surprise for me has been to see the quality of these people's lives. Because they are poor and suffering and uneducated, we often tend to underestimate them. I found that these same people are just as intelligent, ambitious and hard working, and their family values are just as good as mine. If they're just given a chance to improve themselves, they are very enthusiastic and capable of doing it.

Q: Through your individual work as well as projects undertaken by the Carter Center, you have become a great figurehead of strength and support for issues of peace, health and human rights. As such, whom do you admire within the humanitarian realm?

A: We work with a lot of people. I would say one of the more generic admirations I have is for all the volunteers who join Habitat for Humanity. We sometimes have as many as 10,000 volunteers that join Rosalynn and me in the annual Jimmy Carter Work Project. It's where we go into a community or country and build a large number of Habitat for Humanity homes for poor people in need over a five-year period. To see the dedication of these volunteers who pay their own way, for instance, from [the US] to the Philippines, South Korea, Mexico or to South Africa [sic]. They provide their own tools, they dedicate a full week or 10 days of their lives and they work side-by-side with families who have never had a decent home but who join in the work and will own their own house. This is the kind of dedication that's just one example of the hundreds of different ways that folks around the world volunteer to help their neighbors.

From a distance, there would be a person like Mother Theresa, whom I was lucky enough to meet before she passed away. I think what makes her contribution so notable is the fact that she did it in almost total obscurity, without any self-promoting publicity. Obviously, there are tens of thousands of people like that around the world who are devoted to humanitarian causes but are never recognized in any way. I've been recognized for the few things I've done because I used to be President of the United States, and I have the image and fame that comes from that exalted position.

I think that the ones that I admire most are the ones that Mother Theresa exemplifies. The Habitat volunteers I just mentioned to you that go year after year or day after day under sometimes the most difficult and private circumstances, and devote their lives or a portion of their lives to helping other people.

The point is that if you're a lawyer, a teacher, a reporter, an editor, a farmer or a builder, obviously your primary duty is to pursue your own profession and to earn a living and take care of your family; that's part of your responsibility. But all of us, including all of those I just mentioned, [and] many others, have an opportunity and an obligation, maybe a duty, to take a portion of our good fortune and invest it in helping others. This is a chance to have a much more exciting, challenging, adventurous, unpredictable and gratifying life. And when we embark on projects that encompass people whom we would otherwise not ever know, the result is always a greater benefit to us than we anticipate, and the benefits always exceed whatever sacrifice of finances, time or effort we invest.

Q: What would you say to inspire others to become involved in humanitarianism?

A: First of all, each one of us has to analyze our inventory--our own talents, abilities and opportunities of influence--and see how it is that we can utilize what we have been given by God for the benefit of others. Secondly, I would say we need to be ambitious about it and not dormant; we need to search for opportunities to help other people have better lives. The third thing is that in my own experience in this realm, when I've [volunteered], I never have found it to be a sacrifice; it's always been a blessing to me--a very gratifying experience.

In every case when I thought I was doing somebody else a favor by building a house or something like that, I found that I got a lot more out of it than I put into it.

In just one year of Carter Center trachoma control activities in the 2000-member village of Mosebo, Ethiopia, 251 people have been treated for active trachoma, which causes blindness. Forty-one patients have received surgery to treat trichiasis, which can cause visual impairment and severe infections, and 367 households have built latrines to lessen infection risks.

The Carter Center provides the tools and means to help farmers in sub-saharan Africa increase their crop yields through agricultural development, sometimes two or even threefold. By increasing the amount of quality food produced, Third World hunger and poverty will be lessened, food security enhanced and national resources protected.

For the full interview and to subscribe to NEED Magazine, please click here.