This is the second in a four-part post on using ecosystems to store carbon. In Part 1, I wrote that the most fundamental task of climate action is to restore the Earth's carbon balance. I described how carbon is captured and stored by natural carbon sinks.

The experts who study the role of soils, forests, grasslands and wetlands in the Earth's carbon cycle have different ideas about how much carbon these ecosystems can keep out of the atmosphere. They all agree on one thing, however:

We must take full advantage of natural "carbon sinks" if we hope to avoid disastrous levels of climate change. Cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from vehicles, power plants and factories is critical, but it is not going to be enough.

To fully appreciate this, we need to know something about CO2. It is naturally present in the atmosphere and throughout the carbon cycle, but human activity is adding more - so much more that we are altering the cycle. Carbon dioxide is by far the most prevalent greenhouse gas. Eighty-five percent of the human CO2 emissions comes from burning fossil fuels. The rest comes from some industrial processes and from changes in the natural sinks.

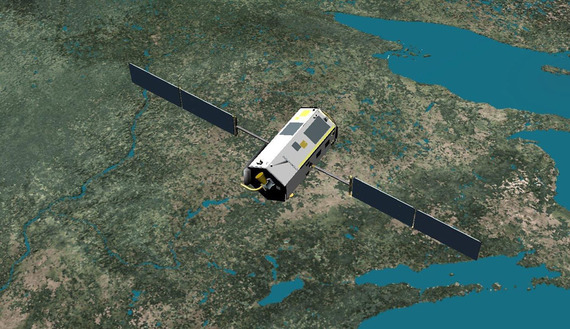

While scientists don't fully understand or agree on the potential of ecosystems to store carbon, some answers may be on the way. In 2014, NASA successfully launched an Orbiting Carbon Observatory that will take more than 100,000 carbon measurements around the world each day to learn more about the carbon cycle. Researchers already have concluded, however, that the CO2 in the atmosphere at its highest level in 15 million to 20 million years.

During 21 years of international climate negotiations, the primary focus has been on reducing carbon emissions from power plants, factories, cars and other human sources. The ability of ecosystems to pull carbon back out of the air now is receiving more attention. As part of the Paris climate agreement, nations submitted plans for factoring "land use changes" into their climate action commitments.

While we might think that environmentalist would be gung-ho for taking better care of forests, wetlands and soils, the increased attention to the carbon-storing benefit of these sinks concerns some environmentalists. They worry that if ecosystems can keep significant amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere, fossil energy companies will feel free to burn more coal, oil and natural gas. The coal industry in particular apparently hopes that natural sinks can help keep coal relevant in a low-carbon economy. At least one organization of coal suppliers and coal-fired utilities - the Western Fuels Association -- hired a Washington consultant to explore the potentials of natural sinks.

Some of the scientists looking into these issues at the U.S. Department of Energy have not discouraged this hope. "The impact of (natural carbon sinks) could help buy time for other technologies to come on-line by delaying the need for more dramatic decreases in global emissions," they wrote in one report.

But the worry is unwarranted. Climate risks are so serious and climate impacts are occurring so rapidly that we need to use all the cost-effective and safe tools in our toolbox.

Besides, there are other good reasons to increase the use of natural carbon sinks at the same time we decrease the combustion of fossil fuels. CO2 is only one of several undesirable pollutants from fossil fuel combustion. The volatility of fossil fuel supplies and prices reportedly has been a factor in most of the economic recessions of the last several decades. In addition, as the ongoing controversy about mountain top removal coal mining, the flap about fracking, oil spills and other accidents show, fossil fuels have other downsides.

Natural carbon sinks on the other hand provide an array of fringe benefits beyond carbon storage, as I detailed in Part 1.

In short, the question we in the United States must answer today is not whether we should make the fullest possible use of natural carbon sinks. We clearly should. The question is how big a job they can do. How much carbon could healthy natural systems store? How do we restore those that have been degraded or destroyed? Which ecosystems offer the greatest opportunities? And how must the stewardship of these ecosystems vary from region to region, or change over time as a result of global warming?

It appears that a growing number of organizations now want to find answers. Among them are two non-profit groups -- Forest Trends and The Nature Conservancy. Along with the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University, they are developing a roadmap on how we can maximize the carbon-storing performance of soils, forests, grasslands and wetlands.

In the process, they hope to identify the full potential of carbon sinks. It is a difficult calculation because so many variables are involved, from changes in the weather to how farmers till their soils, how ranchers manage their grazing lands, how cities use trees and green spaces, and how the federal government manages public lands.

Variables like these have resulted in widely different estimates in the past. DOE and several of its national laboratories estimated in 1999 that natural carbon sinks worldwide were removing about 2 gigatons of carbon annually from the atmosphere. That's roughly equivalent to the weight of more than 100 million elephants or 6 million blue whales. The labs concluded that an ambitious international effort could remove five times that much carbon from the atmosphere, more than 10 gigatons each year.

"It seems reasonable to assume that advanced science, technology and management can double the capacity (of biological carbon sequestration) at low additional costs," DOE's experts said in another report. "TBCS (terrestrial biological carbon sequestration) offers potential for sequestering more than 50% of projected excess CO2 that will have to be managed over the next century."

Other researchers have concluded that natural sinks can make only a modest contribution to carbon storage. Forest Trends and The Natural Conservancy hope to resolve some of these inconsistencies and to identify the path to restoring and protecting the sinks.

But again, we don't need more study to know that natural carbon sinks must be used to their full potential. Today, they store about 16% of the United States' annual CO2 emissions from fossil energy combustion. There are persistent predictions among experts that unless we practice better stewardship of these ecosystems, their performance will decline in the years ahead, even to the point of jeopardizing the nation's climate action goals.

In short, the three-part formula for avoiding catastrophic global warming is to remove less carbon from the Earth, put less of it into the sky and capture more of it in nature's carbon sinks.

Photo: Artist's concept of NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory. Photo Credit: NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Part 3 will explore the pluses and minuses of relying on technical fixes to the problem of carbon emissions.