I met Si Lewen's art before I met him. A friend who learned about him through the documentary "The Ritchie Boys" suggested I go to his website to get a sense of his art. It amazed me: canvases exploding with color, vibrant, pulsing with life. The art became even more amazing when I read the story of Si Lewen's life. He grew up in Lublin, Poland and knew from the age of five that he wanted to create art.

He fled Poland when Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, and through the good graces of Senator Byrd, who was grateful to Si's uncle for having sponsored the senator's brother, Admiral Byrd, in his expedition to the Antarctica, was able to get to the United States. But Si quickly discovered the dark side of the new world, when, during a walk through Central Park, he was robbed at gunpoint and beaten by a policeman who hissed in his ear, "You goddamn Jew bastard."

When World War II began, Si enlisted and became a Ritchie Boy, a member of a special military intelligence unit chosen by the Army because of their fluency in German and familiarity with Germany. They entered Europe on D-Day and undertook covert operations. Si saw action from Normandy through France and back into Germany, where he was among the liberators of Buchenwald. There he witnessed what could have been his fate, and upon returning home, he did not feel able to create art.

"When I returned from the war, I was disgusted. I wanted nothing to do with that experience. I didn't even want to paint." But he found himself drawn to the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League in New York, where he began taking classes and painting landscapes, still lifes and nudes. His work sold and was exhibited in the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. But scenes from his war experiences haunted him.

"I would wake up with these nagging images," Si said, "images that would not go away." He turned to art, creating "A Journey," 70 black and white narrative drawings that turn the viewer into a witness of a Nazi concentration camp. The lack of color in the drawings expresses how in terrifying moments, color disappears. "Even blood was not red."

The drawings convey the shock and horror the liberators experienced on a level that I had not experienced before, even after hearings over scores of veterans recount their stories. Towards the end of "The Journey," the commandant of the camp invites the visitor to a dinner of death, and when the visitor refuses, they become another victim. But the last drawings show the visitor's spirit flying away on the wings of a bird.

Si does not believe that his art has diminished his trauma. He believes it has sustained him, helped to keep him alive. I think of the words of another liberator whom I met in January. Like my father, he was among the liberators of Nordhausen. At the end of our 75 minutes of talking, he turned to his wife and said, "I have struggled to stay alive every day since Nordhausen."

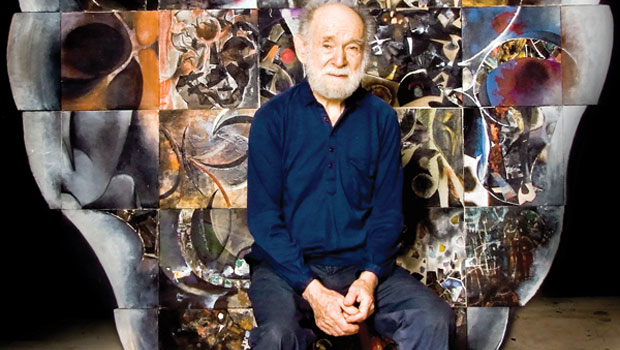

For Si, creating art, living amidst color, is central to that struggle. He showed me the wall of his bedroom that he wakes up seeing every morning: 50 canvases of color. Deep, rich color. "This is what I need to wake to. I need color as much as I need oxygen and water."

Si opened a door for me on understanding why I have always craved color. It has fed my spirit and helped me to heal from my childhood trauma. It has sustained me during my struggle to prevail.

While art might not be able to restore the lost aspects of ourselves, it can support us. And it teaches and heals others. As Si wrote to me, "I believe in the healing power of art -- and not just for the artist. We need art to light up life's dark moments."