Up to now, the only treatment for obesity that has produced significant long-term weight loss is

. Bariatric surgery has risks, is expensive, and 20-30 percent

, or they regain it. Besides, shouldn't we be treating the underlying cause of obesity rather than the symptom?

You might say, "The underlying cause is poor lifestyle." Yet significantly obese people have the quality of life rating of people with cancer on chemotherapy. If simply eating healthy and exercising would cure their problem, why don't they do so, lose weight, and not be miserable anymore? Something else is going on.

What otherwise might we do? Residential programs, e.g. fat camps and obesity rehabilitation centers, produce large weight loss, not as good as surgery, but much better than traditional programs. Could we replicate what's accomplished at residential centers in the real world at a much lower cost?

Residential programs accomplish essentially "forced food withdrawal." This brings to mind what's undertaken at drug addiction rehab centers. In fact, there's mounting evidence that overeating and obesity involve an addictive process. Brains of obese individuals show similarities to the brains of drug addicts, and the relationship with food described by obese individuals satisfies DSM addiction criteria.

How might forced food withdrawal be accomplished in the outside world, similar to residential centers? Withdrawal from food is trickier than withdrawal from a drug, because totally quitting food isn't feasible. Nonetheless, it is feasible both to totally stop snacking and to gradually decrease excessive portions at meals.

What kinds of foods necessitate withdrawal? First, specific "problem foods" of the individual, which produce cravings and are irresistible -- so-called "feel good foods," resembling a "drug-of-choice." Candy, chocolate, soda, pizza, chips (crisps), and fast food are examples. Problem foods appear to be a "sensory" addiction (taste, texture) rather than a direct effect of food ingredients, e.g. sugar, on the brain. Bulimics, for example, vomit/purge, yet still become addicted to sweets.

Secondly, non-specific foods -- whatever is available in the moment. Most snacking and mealtime foods are in this category. This is "nervous eating," similar to nail biting and skin picking. The brain tends to glom onto any behavior that relieves stress, in this case eating. A "behavioral" addiction results and involves the mechanical actions of eating -- biting, chewing, crunching, hand-to-mouth motion, and especially swallowing. All overeating represents a mixture of the sensory and behavioral addiction components, although the ratio varies. The combination comprises "eating addiction."

We implemented an intervention for eating addiction as a smartphone app and published a study of a trial

with the app in a peer-reviewed journal.

The app treats the two components separately but in parallel. The sensory addiction component is treated similarly to drug addiction by withdrawal/abstinence, first from each problem food, one-by-one, until cravings or difficulty resisting the food resolve. Next comes withdrawal from snacking (non-specific foods), accomplished by advancing snack stoppage time periods -- morning, afternoon, evening, night time -- with the aim of zero snacking for the entire day. Lastly, withdrawal from excessive portions at home meals is achieved by weighing and recording typical amounts of frequent foods served and incrementally reducing amounts.

The behavioral addiction component is treated by: a) viewing gross photos or videos (e.g. draining pus) or snapping a rubber band against the wrist to quell eating urges, b) avoiding triggers (e.g. kitchen, boredom), c) relaxation (e.g. deep breaths), d) alternative behaviors (e.g. squeezing hands), e) distractions (e.g. reading), f) distress tolerance (e.g. urge surfing), and g) keeping hands busy while watching TV (e.g. drawing). Decreasing portion amounts at mealtimes is behaviorally facilitated by staying away from extra food (e.g. serving food in one room and eating it in another).

Withdrawal from problem foods and snacking produced minimal withdrawal symptoms among participants in our study. However, withdrawal from excessive portions produced nagging urges, agitation, and outright anger, although rarely true hunger (e.g. stomach growling). Yet, participants described most food withdrawal symptoms as "hunger." Participants displayed obfuscation, rationalization, deflection, denial, cheating, and lying -- resembling drug addicts.

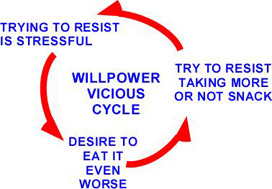

Participants experienced a willpower vicious cycle when trying to resist taking more at meals, or not snacking. Resisting, itself, was stressful, yet they coped with stress by eating -- a no-win situation. A 10-year-old boy exclaimed, "Weighing my foods and trying not to take more when more food is sitting there drives me crazy." His mom observed, "He gets less upset if the food is presented to him already weighed rather than him having to do it." With the mom weighing his foods, this boy happily lost weight until his mom got sick one day. He became so stressed weighing his foods that his mom had to get out of bed and do it for him. His eventual solution was simply relaxing when weighing his foods and then distracting himself.

In summary, this app uses addiction treatment methods to achieve zero snacking and reduced mealtime amounts, as an intervention for eating addiction and obesity. The sensory addiction component responds to classic addiction withdrawal methods. The behavioral addiction component responds to behavioral addiction methods. Lack of motivation appears due to fear of withdrawal symptoms and fear of losing a major coping mechanism (eating).

Support HuffPost

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

At HuffPost, we believe that everyone needs high-quality journalism, but we understand that not everyone can afford to pay for expensive news subscriptions. That is why we are committed to providing deeply reported, carefully fact-checked news that is freely accessible to everyone.

Whether you come to HuffPost for updates on the 2024 presidential race, hard-hitting investigations into critical issues facing our country today, or trending stories that make you laugh, we appreciate you. The truth is, news costs money to produce, and we are proud that we have never put our stories behind an expensive paywall.

Would you join us to help keep our stories free for all? Your contribution of as little as $2 will go a long way.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you’ll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.