Laughter is the best medicine, unless mocking others gets you killed as with Charlie Hebdo, but that hasn't stopped comic strip artists from skewering people and institutions down the ages.

Except cartoon characters aren't always funny. There's a serious dimension to their messages.

A rich collection of such work from when the genre was established to modern fare is enshrined at the must-see Centre Belge de la Bande Déssinée (Belgian Comic Strip Center) in Brussels.

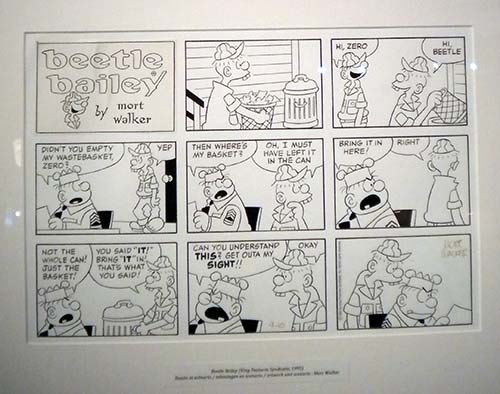

But perhaps the funny strips, from three boxes to full pages and book series, that cover political, economic, social and other issues, are what strike readers the most.

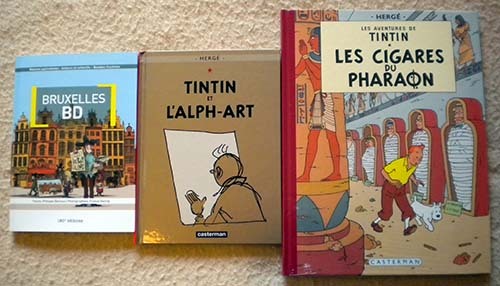

A precursor to today's foreign correspondent is none other than Tintin and his white terrier Milou (Snowy to Americans) created by Belgian cartoonist Hergé, pen name of Georges Prosper Rémi.

The comic albums launched in 1929 feature Tintin as nobody, and Tintin as Everyman.

The young man travels the world in search of adventure and writes about his escapades involving Captain Haddock, Prof. Tournesol (Calculus), Dupont et Dupont (the Thomson twins) and a host of other charming characters.

His face is made up of a very few simple features. It's almost expressionless. Because it is neutral, it's the ideal recipient for the emotions felt and projected by readers.

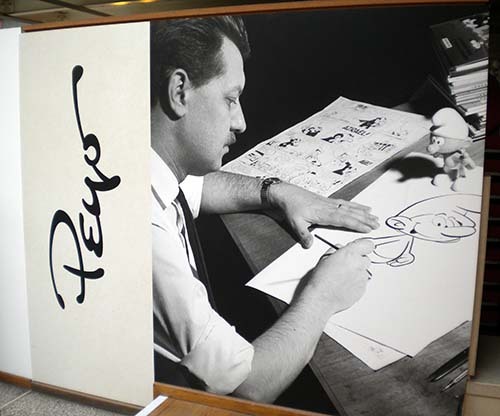

Another Belgian icon is Pierre Culliford, a/k/a Peyo, creator of Les Schtroumpfs (The Smurfs) and their adventures in a forest's mushroom village.

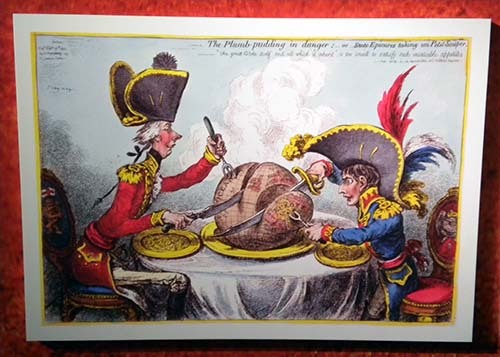

The comic strip as a genre, museum historians say, dates back to cave men who neither read nor wrote, but through the centuries the aim has been the same: tell a story, and hopefully get a reaction.

Interestingly, it's monks who invented the comic strip's grammar, we're told.

Copyists in Middle Ages Christian monasteries reproduced sacred texts, embellished them with intricate illuminations and illustrations rendering thanks to God, and, without realizing it, invented most of the principles used by modern artists to create a comic strip: dividing the story up into panels, movement, foreground, and dialogues in balloons.

There are also historical comic strips that range from the strict recounting of historical facts, to fictionalized intrigues based on real events and are drawn in realistic, semi-realistic or simply humorous form, according to museum experts.

All periods are evoked, from the legend of Gilgamesh to the Gulf War, with a predilection for Ancient Rome, the Middle Ages and the Napoleonic Wars.

Fast-forward to the 20th Century when comic strips took on a life of their own, became animated, went from 2D to 3D, discovered marketing, morphed into a mega industry, and started raking in millions of dollars.

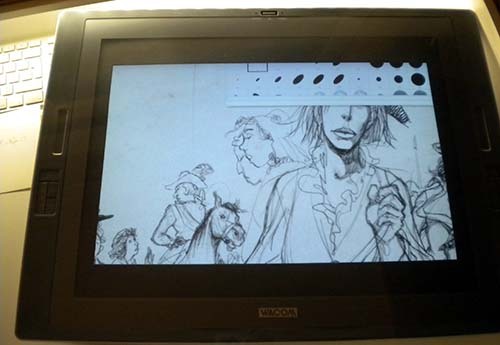

Today's digital art has illustrators using computers to finalize their works, drawn first on paper, then scanned and corrected. Either the artists finish their plates or combine them by computer.

Some even forgo paper and draw straight onto graphics tablets connected to computers that provide flexibility for all styles of illustration.

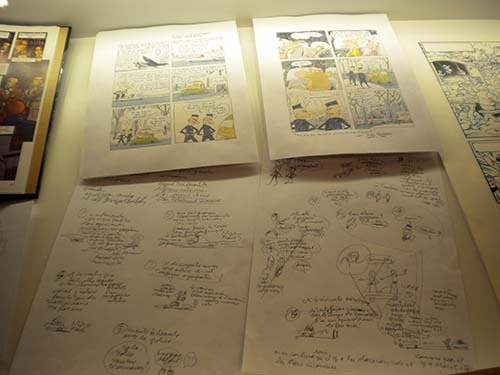

In an earlier era, it was strictly pencil drawings coupled with a "scenario" provided by a writer.

Frequently the illustrator and narrator are one and the same.

The artist sketches out the portraits of the main characters, draws studies of their costumes and backgrounds against which the action will be set, museum experts say, adding that it's a period of intensive documentary research.

Those authors who can afford to often go themselves to research the locations and take the photos they will need later on. To visualize the work to be done, the artist creates a storyboard by sketching out the pages for the future album very small, with small boxes and speech bubbles that prefigure the action on each page. Armed with all this information, the artist can finally make a start on the actual drawings.

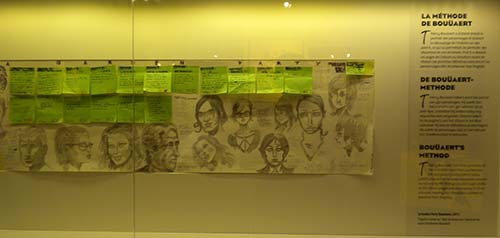

An original technique is the Bouuaert method, named after Thierry Bouuaert who first drew portraits of his characters and then worked out the storyboard using post-it notes.

It allowed him to swap sequences around as necessary, an explanation of one of his illustrations reads.

He then produced rough drafts of the album pages before drawing his final artwork, and left the characters un-inked to preserve their fragility.

American readers are probably best acquainted with science fiction and action comic strips, described as "a very Anglo-Saxon genre before being adopted by many European and in particular French-Belgian authors."

The most committed writers willingly use this medium to evoke failings of our society by transposing them into imaginary worlds often ruled by totalitarian regimes.

Ironically, comic strips that criticize money-hungry characters have benefited from the sales of books, the licensing of comics-related objects, movies, videos and online offerings.

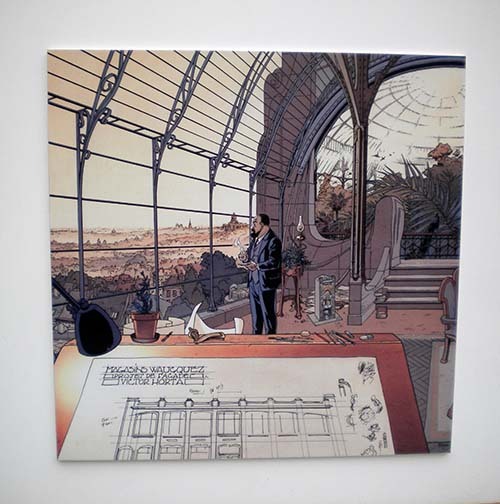

The museum's history is also noteworthy.

It was initially a cloth and fabric shop designed and constructed over a century ago as a semi-industrial building by Victor Horta for merchant Charles Waucquez.

It was like the concourse of a station, surrounded by the balustrades of the two upper stories, intersected by hanging staircases, and with suspension bridges built across it. The iron staircases with double spirals opened out in bold curves multiplying the landings.

The shop survived for 70 years, closed in 1970 when "20th Century progress" got the better of it but was purchased by the Belgian federal state in 1984 and eventually turned into a museum devoted to the comic strip.

The project also aimed to preserve its stained glass masterpieces, arabesques and staircases.