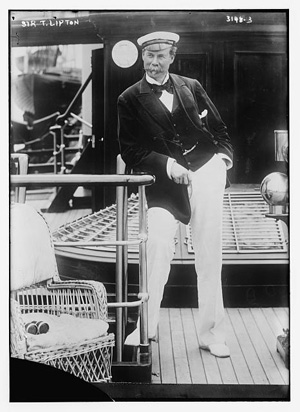

July 4, 1930 dawned in a Glasgow neighborhood called the Gorbals five hours before it arrived in the United States. By the time New York awakened, hundreds of Scottish boys and girls had found their spots on the cobblestones of Lancefield Street to wait for their version of a true American, Sir Thomas Lipton. They cheered when a car wheeled down the street, pulled to a stop next to a warehouse, and The Great Lipton (a name he had given himself) emerged wearing his trademark yachting cap, blue suit, and polka dot tie.

Wherever he was in the world, Lipton always celebrated American Independence Day in a big way. Here in Glasgow he would hand out cookies and chocolates until the very last child was served. With the Great Depression settling like a fog on the once great city, the sweets were a rare treat for the children. But Lipton's real gift was the hope he instilled in so many hearts. He was born in the Gorbals in 1848, a time when life was even harder. A fifth of the children, including his sister, died before age five. When Friedrich Engels visited he saw such "filth, misery, crime and disease" that he considered it the worst industrial slum in the world.

Lipton's rise to wealth and fame was so well known that almost anyone on either side of the Atlantic could recite it. Barely educated, a teenage Tommy had gone to America at the end of the Civil War and tramped around the country learning all he could from men who, uninhibited by class or a shortage of cash, hustled their way to success. He went home to establish the world's first chain of grocery stores, which eventually numbered 300. He succeeded with heaps of advertising, parades featuring elephants and pigs, and stunts like hiding gold coins in wheels of cheeses. He also sold quality goods at low prices in immaculate, well-lighted shops.

As his empire grew to include factories, farms, and the biggest tea business in the world, so did the Lipton persona. He dressed like a dandy, sprouted a big walrus moustache, and mastered the art of the Grand Gesture. When the Princess of Wales was unable to raise enough money to give the poor a banquet on Queen Victoria's Jubilee, Lipton supplied the funds and mobilized an army to serve 400,000 meals. Rewarded with a knighthood, Sir Thomas became the future King Edward VII's close friend and, as a friend would, he gave the cuckolded husband of Edward's mistress a position in his New York office. He used his influence with Edward to promote peace in Ireland and during the Great War he outfitted a hospital ship and sailed with it to save wounded civilians.

In New York, where he oversaw vast American holdings, Lipton came to represent everything the Yanks liked about the British. He was cheerful, energetic, and charming. The public swooned when they read of his generosity during the Jubilee, but they adopted him as their own when he rescued The America's Cup challenge race from a petulant lord who had made such a fuss when he lost that it seemed that the world's greatest sporting event might never be staged again.

Lipton saved the cup tradition with a yacht he named Shamrock and the most gracious conduct ever seen in a man who was thrashed in three straight races. He would return, and lose, four more challenges in the same splendid way. By the time of his last campaign, in the same summer when he visited Lancefield Street on the Fourth of July, he was such a well-loved loser that his Shamrock V claimed more fans the than the New York Yacht Club boat and Will Rogers called upon his countrymen to throw the races. They refused. Lipton lost. But the Americans gave him a prize anyway at a great celebration presided over by Mayor Jimmy Walker. When he died a year later, Glasgow gave Lipton the equivalent of a state funeral.

The love that was heaped upon Sir Thomas during his lifetime and at his death was his reward for a life that inspired millions. He always credited America with the traits the defined him. These included resilience, ambition, optimism and a firm belief that he could always invent and then re-invent himself. It was this sense of autonomy that Lipton celebrated every Fourth of July. It was also America's gift to the world.