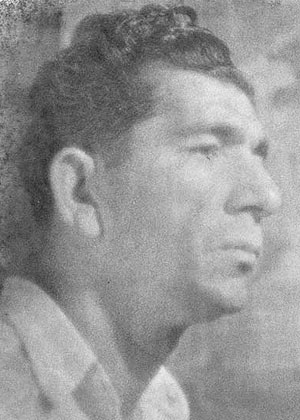

The last known photo of artist Arman Tateos Manookian (1904-1931)

Arshile Gorky, the subject of a retrospective exhibition now on view at MOCA in downtown Los Angeles, was an Armenian American and a genius. Both his achievements as an artist and his tragic life story have been widely acknowledged, as they deserve to be. Perhaps the only part of Gorky's life story that anyone would take issue with is the statement that he survived the Armenian Genocide: to this day the government of Turkey does not acknowledge that a genocide occurred.

Our president has deferred to that view. Using carefully chosen language meant to appease Turkey, President Obama said in a recent speech that in April of 1915 "...one of the worst atrocities of the 20th century began." In other words the events that led to Gorky's mother dying of starvation in his arms came about as the result of "atrocities" but not "genocide."

In April of 2009, the House of Representatives of the state of Hawaii -- our President's home state -- adopted a formal measure setting aside April 24th as a "Day of Remembrance in Recognition of and Commemoration of the Armenian Genocide of 1915." The language of the bill includes the following:

WHEREAS, Armenia's ties to Hawaii started in the 1920s with the gifted painter Arman T. Manookian, a genocide survivor, who lived in Hawaii for almost six years before his tragic death in 1931, and who became known as Hawaii's Van Gogh...

Hawaii, it seems, has recognized that a genocide did indeed occur. It is also heartening that the language of the resolution acknowledged the life and art of another Armenian American artist of genius: Arman Manookian. His life history and art are also compelling and there are more than a few parallels with Gorky's story. Both men were modernists, genocide survivors, and suicides.

The problem in studying Manookian is that he left few traces. Less than 30 oil paintings by him are known to survive, and they are mainly in Hawaiian private collections. Information has also been scarce. At the time I first learned about Manookian in 1999 even those who cherished his art knew next to nothing about his life. Mainly, they had heard a few stories about the artist's wild temper. The collector who owned the largest group of his works did not even realize that Manookian was an Armenian.

That was the situation when I started a two year research project to learn more about Arman Manookian. After a year of searching, a letter I obtained from the Marine Corps Historical Center in Washington D.C. led me to Manookian's nephew and elderly sister-in-law in France. The family history that they provided created the foundation for a new understanding of the artist.

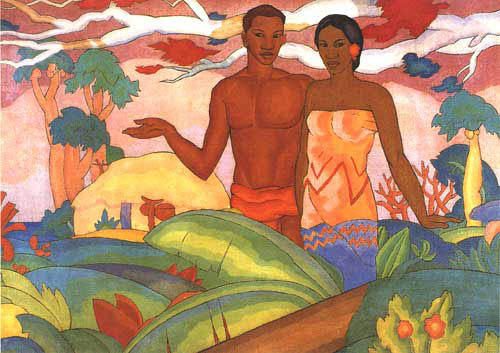

Arman Manookian "Hawaiian Boy and Girl" Collection of John and Patsy Dilks

Among the facts that I was able to discover was that Manookian, who grew up in Istanbul, was once a student at the school of "St. Gregory the Illuminator." The principal of that school, Daniel Varoujan, was a leading Armenian intellectual who was tortured and then executed by Turkish authorities in April of 1915. Although the artist's heirs had only sketchy information to share about what ten year old Arman and his brother Vahe had witnessed in 1915, another artist, the late Jirayr Zorthian, once told me that as a four year old in Istanbul he saw Armenian bodies hanging from telegraph poles.

In 1999 I was only able to find one living person who remembered Manookian. Her name was Anne Simms Stubenberg, and she recalled that Manookian, gave her painting lessons at the age of 7, had once angrily picked her up by the hair. Other stories, which had been passed on through the years included several about public tantrums in which he destroyed his own works. Manookian may have been living in paradise, and painting it too, but his life had been poisoned at the root.

Manookian's childhood, like Gorky's, was shaped by genocide, the systematic killing of a racial or cultural group. If he really was "Hawaii's Van Gogh," a troubled genius trying to remake his life in vivid color, there were very good reasons that for the pain that drove his artistic quest. When it happened to Armenians, the word genocide had not even been invented. It came along later after World War II in an attempt to describe what had happened to Jews in Europe. Before then, according to some, the world only had atrocities.

* * *

If you would like to know about Arman Manookian, here is an article that I wrote about him for the Armenian Reporter in October of 2008.

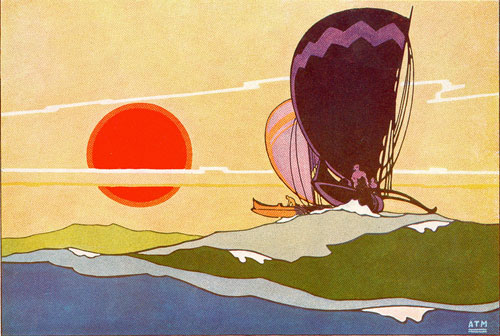

Arman Manookian, Polynesian Explorers, color engraving after a painting

Arman Manookian: Hawaii's Van Gogh

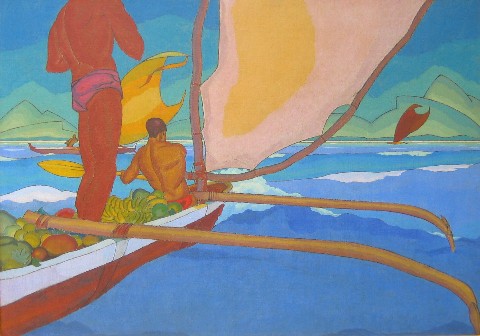

In the lobby of the exclusive Hotel Hana-Maui hangs a striking painting of two Hawaiian outrigger canoes. The vessels, manned by silhouetted figures, rise on the crest of stylized green waves while the giant orange disc of the sun shines above an island in the distance. This vivid icon, which idealizes and celebrates the image of the Hawaiian Islands before the arrival of Europeans, is the work of an Armenian-American artist, Arman Tateos Manookian.

Outside of the Hawaiian Islands, few people have ever heard of him. He died young - he took his own life at the age of 27 - and less than 30 of his oil paintings can be accounted for. Still, to those who knew him, Manookian was a legendary and fascinating figure. "For years after his demise," said writer and historian Julius Rodman, "his legend was very much alive in Honolulu."

Born Tateos Manookian in 1904, the artist grew up in Constantinople. He was the eldest son of a family that owned a newspaper. As a boy, he saw the "Great White Fleet" appear in the harbor, and among his first recorded artworks are images of American military vessels. Tateos received an excellent education at the School of St. Gregory the Illuminator, where the headmaster was Daniel Varoujan, one of the greatest poets of the era and leader of the Mehyan literary movement.

During the years of terror and genocide that unfolded as Tateos grew to adulthood, his father, Arshag, managed to escape capture by the Turks, but died of influenza in France. Forever scarred by the terrors and losses of his childhood, Tateos Manookian arrived in Ellis Island in 1920 at the age of 16, hoping, like so many Armenian immigrants, to begin life anew in America.

After attending the Rhode Island School of Design, where he studied illustration on a state scholarship, he spent time in New York and took additional classes at the Art Students League. At this time he changed his name to Arman Manookian and enlisted in the Marines, in 1923. Within a year he was working as a clerk for Edwin North McClellan, a writer and historian. McClellan noticed Manookian's skill as an illustrator, and soon had the young man at work providing illustrations for Leatherneck magazine, and also for a history of the Marine Corps.

When McClellan was assigned to Pearl Harbor in June 1925, Manookian went with him. Manookian arrived in Hawaii eight years before the first Pam Am seaplane would arrive, and fourteen years until the attack on Pearl Harbor. The beauty and culture of the place fired the young artist's imagination. In 1928, he was quoted in Paradise of the Pacific magazine as saying that "... in all his travels he has come upon no more intriguing paradise than these mid-Pacific gardens of the gods."

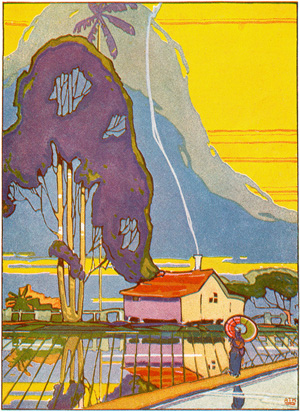

Arman Manookian "Ricefields," a work on paper created for a cover of "Paradise of the Pacific"

Even in paradise, Manookian was a restless, temperamental man who tested his friends. In April 1926, he walked off his post before being relieved, and only a strong legal defense crafted by his friend McClellan helped him avoid court martial. After his death, the Honolulu newspaperman Arthur Greene recalled that behind Manookian's back people would whisper "He is mad and will die in some mad way."

In September 1927, Manookian left the Marine Corps to pursue an artistic career, taking a job with the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. His reputation grew after his elegant ink drawings and vivid paintings began to appear in Paradise of the Pacific, which published a profile of him in 1928.

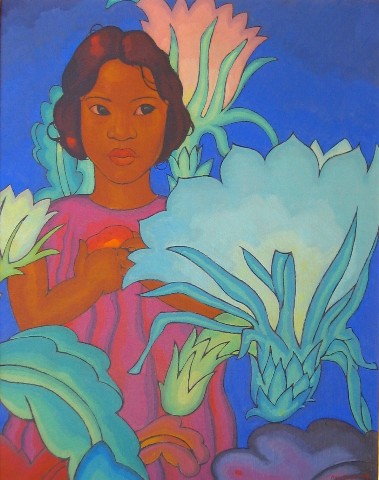

In his six years in Hawaii, Manookian bloomed as an artist, just as Vincent Van Gogh had during his sojourn in Arles. Manookian wandered in the pristine Manoa Hills, marveling at the exotic flora. He also loved to sketch the ramshackle homes that could still be found on the local beaches, and was charmed by the Hawaiian people, whom he often painted with classical dignity. Manookian painted mythological and historical scenes with equal fervor, infusing them with drama and energy.

The artworks Manookian created in Hawaii demonstrated both his training as an illustrator and his willingness to experiment with vivid, expressive color harmonies. In fact, color became his trademark. Manookian's use of bold hues, which reflected his absorption of Byzantine color as a young man, was challenging to those who first saw them, including visitors to his one-man show at the Honolulu Academy in May 1928.

Responding in a news article to comments made by visitors to the show, the artist explained:

Now the colors: they are not supposed to stagger one; that was not the aim. In fact, my mind was quite free from such a diabolical idea. I did not try to achieve the illustration of a tropical heat nor the allurements of a moonlit night.

Manookian, who saw himself not as a modern artist but one grounded in the Renaissance tradition, believed that his works represented "... the achievement of aesthetic satisfaction in color and form." Arthur Greene would write in his eulogy of Manookian: "His was the dream of creating in color a great symphony of beauty."

Arman Manookian, "Polynesian Girl," Oil on Board, 30 x 24 inches, Private Collection

In a review of the Honolulu Academy show, critic Clifford Gessler stated: "There is a great deal of strength in his work, largely done, as it is, in simple masses of color. There is sincerity and conviction in it, and one feels that it bears a potential richness for the future."

A cultivated esthete, Manookian was fascinated by the French novelist Gustave Flaubert's Salammbo, a historical novel set in ancient Carthage. He admired the works of the philosopher-poet George Santayana, and had a fascination with the film star Greta Garbo.

Manookian had a grandiose sense of self and didn't hesitate to challenge people whose ideas he considered complacent or ignorant. His temper often led him into heated discussions about art and culture, and he was often dissatisfied with his own work. One family in Honolulu still treasures a painting on paper that he tore in half following a public tantrum. After an extended visit at the home of one Honolulu couple, Manookian threw the four paintings he had completed while there into the trash. After his departure, the couple fished them out and kept the works.

In May 1931, after completing a final commission, the artist drank poison and fell dead on the kitchen floor of the house he was sharing with friends. Because of the pain and intrigue surrounding his death - he reportedly was upset over a broken love affair - his reputation as an artist suffered. In the late 1950s, his final painting was found on a curbside in Honolulu and rescued by a family that recognized its value. Today that painting is being offered for a six-figure price by a private dealer in Hawaii. One of Manookian's finest works, originally created as a mural for a Honolulu restaurant, reportedly sold for $500,000 in 2005.

Arman Manookian, "Men in an Outrigger Canoe Headed for Shore,"

Oil on canvas mounted on board, 47 5/8 x 67 7/8, Private Collection

Manookian is still relatively unknown on the U. S. mainland, where Arshile Gorky, who also came to America in the aftermath of the Genocide, is recognized as the greatest Armenian-American artist. It is time for a major U.S. museum to gather Manookian's rare works and ask the mainland public for a new assessment of his achievement. In Hawaii, those who know his work have had time to form their opinions.

Ronn Ronck, a former arts editor of the Honolulu Advertiser and an author of several books about Hawaii, calls Manookian's art "unique and unforgettable." Ronck further comments that "Manookian had the gift of genius, and, if he had not died so tragically young, even of greatness."