Wangechi Mutu, Yinka Shonibare, Aida Muluneh, Dante Alighieri.

These are some of the brilliant minds involved in "The Divine Comedy," a contemporary art exhibition at the the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art. One of these names, as you may have keenly ascertained, is not like the other. Dante's Italian heritage and an approximately 700-year age gap certainly separate him from the other figures listed on the press release. But 40 contemporary African artists have assembled in his honor, each creating an artistic homage to his timeless depictions of heaven, purgatory and hell.

Yinka Shonibare, How to Blow Up Two Heads at Once (Gentlemen), 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Colecçõ Sindika Dokolo, Luanda.

The sprawling exhibition is divided into three categories, with a selection of artists each addressing themes associated with Dante's three poems. While a majority of religion-centric art exhibitions feature some combination of heavy-handed symbolism, oddly proportioned babies and golden halos, this exhibition opts for a rather different vibe.

For exmaple, Shonibare's "How to Blow Up Two Heads at Once (Gentlemen)" features two headless gentlemen clad in electric hued, vaguely imperial looking suits. The wild fabrics, which are actually manufactured in the Netherlands, embody the paradoxical nature of identity throughout Shonibare's work. And then there's Wangechi Mutu's hypnotic collage, depicting a shadowy creature with a swarm of dark somethings emerging from her ruptured midsection.

We spoke to Mutu about her featured work and the exhibition in general.

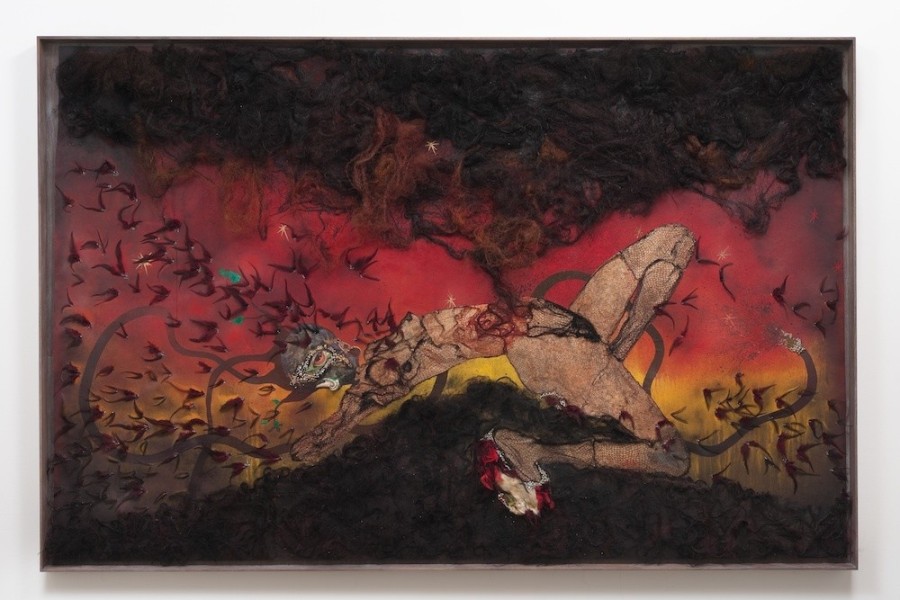

Wangechi Mutu, The storm has finally made it out of me Alhamdulillah, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer

What was your relationship to Dante's text prior to this exhibition?

I don't think we as artists had to have any relationship to the text. The curator started discussing The Divine Comedy as a premise for an exhibition maybe four years ago. At that point I wasn't sure what I was going to put in as a work, but I felt that a lot of my work revolved around Catholicism as an inspiration in some way. It was, for better or worse, my foundational bedrock schooling, not in belief -- I was raised Protestant -- but I went to Catholic school for 12 years. I have a distinct memory of the masses, the imagery, the particular type of Christian teaching that Catholicism professes. I've read some of Dante's Divine Comedy, but not all of it. But the theme is serving more as kind of a map to place a lot of different artists' work. It's a contemporary African art show. It is designed to surprise.

How did you settle upon your featured piece, "The storm has finally made it out of me Alhamdulillah"?

My first work for "The Divine Comedy" was "Metha" but it didn't make it to the American venues. My choice of work has been changed to "The storm has finally made it out of me Alhamdulillah." When I was making the big painting collage it had nothing to do with "The Divine Comedy." It does have something to do with a personal journey, where I kind of descended into a very unknown, dark place and eventually, out of some turn of fate, things changed. I did go to purgatory and back, not quite hell. I'm situated in hell in the exhibition, however.

What does the show's version of hell look like?

Hell has a lot more space for a lot more characters -- different types of mythologies and people and images. It also begs the question: where is this awful place and how do people end up here? A lot of my work is pointing at human failing and in a beautiful or strange way highlighting our weaknesses, our prejudices, our fears, vanity, greed, a loss of compassion. All of these things. Lately in my work I've been questioning the feeling of hell on Earth, which is something humans have created through war and misrepresentation and inhumanity.

Aida Muluneh, 99 Series, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Going back to "The storm has finally made it out of me Alhamdulillah," who is this creature?

All of my work has a figurative element to it. There's often a character. There are some works that look a little like organisms, like a cell or a piece of vomit. I usually have a dominant character or a portrait with a face -- some kind of expressive being. I was trying a lot to find new material that could handle my heavier materials, all of the heavy beading and branches and hair. The piece is full of hair. The cloud emerging out of the creature's belly is actually lots and lots of synthetic hair, a big billowy cloud of it. There are also these little creatures and birds flying around; she is attracting flies of feathers and beads.

And what is her story?

The idea, for me, is about having to translate my experiences because they're from somewhere else, being very aware of my status as an immigrant. This show was pointing at the ability to finally go home. The storm finally made it out of me. It's self prophetic, a self-portrait of this thing being born out of me. If you think of a problem as something you create as opposed to something thrust upon you. It removed itself; it was exercised. It was coming out of the belly of the beast.

Your work transforms a very traditional subject matter -- religious art -- into something provocative, paradoxical and contemporary. Is this important to your practice?

I'm not as concerned with religious art as I am with dogmas in general. We create these belief systems and initially they are transgressive and radical, and a few hundred or thousand years into them the new thought becomes something unmovable, something we use to to oppress each other in cruel ways. For me it's less about religion and more about being allowed to be critical in work, in ways that may seem blasphemous to overzealous people. Being allowed to kind of say the things that are problematic and unusual about everything -- government, religion, education, ways of representing women, ways of representing history and culture.

Artists are often the kind of people who are questioners and truth seekers but also cheeky in how they represent their ideas. I think it's definitely about Catholicism as a metaphor for a world order. You could translate that to any other school of thought that has ballooned out of control and become above the law. That is my interpretation, what I think about a lot in my own work. This is how I approach my entire practice, seeing what's out there that interests me but has remnants of the traditional, the conservative. How do we make these thoughts ready to follow our living today?

"The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists" runs from October 16 to January 25, 2015 at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia. Get a taste of the afterlife below.