Theatre pundits have it that this year's Tony for Best Play will go to James Lapine's new play, Act One, based on director Moss Hart's memoir of the same name.

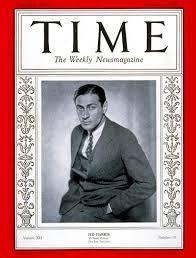

Both memoir and play center on young Moss's collaboration with the great George S. Kauffman, but that's not why I went to see it. I went because Act One features Jed Harris, the theatrical wunderkind of his day, with a touch of Max Bialystock thrown in. Harris produced and directed thirty-one shows between 1925 and 1956, many of them huge hits, among them Pulitzer Prize winner, Our Town and Tony award winner, The Crucible.

When I was a child my mother was Jed's maid. After I grew up, he tracked me down to work as his personal assistant as he attempted to produce one last play called Great Day For the Race.

Proudly announcing that I was an actress with no interest being an assistant to anyone, I let Jed seduce me with the promise of a hundred dollars a week (that he couldn't pay) and maybe understudying the girl.

By now Jed was a lonely old man, a drunk crippled by debt and delusion, while I was fresh out of NYU with an MA in English and Delusion. On that first day, when he opened the door to his dark, smoke-filled sublet, Jed reminded me of T.S. Eliot's anti-hero, J. Alfred Prufrock. He might well have greeted me with "I grow old...I grow old...I have heard the mermaids singing each to each. I do not think that they will sing to me."

The mermaids were gone, as were his cronies. I was the only one left -- Alice M'rie, that little Irish girl brought to his apartment every Saturday morning by her mother to "help Jed out."

Attending Act One was strange. Especially seeing Jed portrayed by Will LeBow in a scene where a startled young Moss encounters a naked Jed Harris shaving in front of a mirror.

The scene works. Yet there's no way an actor could truly portray Jed's sinister, charming sneer of a smile, framed by those glittery black slits of eyes without meeting him face to face. The audience titters wondering would someone as famous as Harris conduct an interview in the nude? He would. From the first moment my mother and I entered his sublet I rarely saw him dressed.

My mother handled this well, considering the Irish aren't one for parading around in their birthday suits. It was Alice M'rie who was shocked. Though he always had an old sheet or towel handy to cover up below, Jed Harris was the first man I ever saw naked.

My job was cleaning an endless array of ashtrays piled high with a week's worth of Salems, as well as washing whisky stained glasses. Jed made it his job to edge-u-cate me. Maybe he recognized in me a touch of the poet. I'd like to think that. Whatever it was, he was intriguing enough for me to dash through my chores, run to his bedroom and sit beside him on the bed, while he regaled me with stories.

Here's how I describe Jed in my memoir I'll Know It When I See It. "Oh, Jed Harris's bed. I see his hairy chest, and hairy upper arms, and hairy back. Yet he has a love child. Not just a child, but a love child. I don't know what it means. But it sounds spicy. Oh, who's afraid of the big bad wolf, the big bad wolf? I am...a little."

And yet, years later, there I am in a mini skirt, still sitting on the edge of an old man's bed watching him frantically dialing numbers, trying to get backers for, as he put it, "The greatest Irish play since Juno and the Paycock."

Jed had no money and no one would give him any. It was so bad he even persuaded my boyfriend to pay for a flight to LA so he could see his old girlfriend, actress Judith Anderson, hoping she'd give him money. She didn't.

The hotel kicked Jed out. He wound up in a maid's room in his sister's apartment, spending his days in bed, smoking, drinking and telling me stories I already knew. I loved him. I hated him. He never did pay me, nor did I get to understudy the girl, for Great Day was never produced in New York. Yet, Jed Harris taught me to worship theatre.

After seeing Act One I Googled Jed and found that but one paltry box of his effects was bequeathed to the University of Ohio. Prufrock says "I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker." Jed must have seen his greatness flicker as he tried to produce one last play.

But I have something better than anything in that box. I have three paintings Jed always carted around with him. Paintings he removed from his sister's wall in a fit of pique. Two watercolors by set designer, Joe Mielziner of Jed's production of Uncle Vanya starring Lillian Gish and Osgood Perkins, Tony Perkins's father, and a large oil painting called 'A Persian Writing Desk'.

Having put me and the paintings in a taxi, Jed disappeared from my life. Shortly before he died in 1979, famed theatrical lawyer Arnold Weissberger called to say that Jed claimed he only "loaned" me the pictures, and wanted them back.

"Ah, you old bastard," I thought, "to treat me like you treated everyone else."

So I wrote Weissberger a saucy letter saying, "The pictures are mine. I performed services for Mr. Harris above and beyond the call of duty."

Like crawling on the street trying to gather pages from the only copy of Great Day that Jed had just flung from a window. Like pulling Jed's drunken head out of a plate of roast beef at Joe Allen's. Like begging bank managers to cash rubber checks. Like calling one of his girlfriends to cancel a date and calling another to make one.

I can see the pictures from where I write and I can see Jed smiling sinisterly at me.