My mother died shortly before her 85th birthday, in a quiet hospital room in Connecticut. One of my brothers was on the phone down the hall, telling me to jump on a plane. We were not a perfect family. She did not die a perfect death. But she avoided what most fear and many ultimately suffer: dying "plugged into machines" in intensive care, or being shocked during a futile cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or dying demented in a nursing home. She died well because she was willing to die too soon rather than too late.

Don't get me wrong: My mother, Valerie de la Harpe Butler, loved life. She and my father, Jeffrey, left their South African homeland in their 20s, bursting with immigrant vigor, raised three children (all of whom ultimately moved to California), and built a prosperous life in the U.S. My father became a college professor. My mother, an amateur artist, practiced Japanese calligraphy and served tea at four without fail. She got breast cancer in her 40s, and after two mastectomies and radiation, she put up her blonde-streaked hair in its classic French twist and returned to the world as the beautiful woman she'd always been. Even as she approached 80, she hiked two miles a day, weeded her garden, and stained her own deck.

My parents and me at my wedding 1985 (Photo by Matt Herron)

She also spent six years as a family caregiver, after my father had a crippling stroke when he was 79 and she was 77. A hastily inserted pacemaker forced his heart to outlive his brain. His medically prolonged dying made her painfully aware of health care's default tendency to promote maximum longevity and maximum treatment. It wasn't what she wanted for herself.

She was not alone. In California, my home state, a 2012 survey by Lake Research Partners and the Coalition for Compassionate Care of California found that 70 percent of state residents want to die at home, and national polls have registered even higher proportions. But in fact, nationally, less than a quarter of us do. Two-fifths die in hospitals, and a tragic one-fifth in intensive care. This is an amazing disconnect in a society that prides itself on freedom of choice.

This disconnect has ruinous economic costs. About a quarter of Medicare's $550 billion annual budget pays for medical treatment in the last year of life, and during that time, one third to one half of Medicare patients spend time in an intensive care unit, where 10 days of futile flailing can cost as much as $323,000. Overtreatment costs the U.S. health care system an estimated $158 billion to $226 billion a year.

Why don't we die the way we say we want to die? Because we say we want good deaths but act as if we won't die at all. Because lifesaving technologies have erased the line between saving a life and prolonging a dying. Because saying "Just shoot me" is not a plan. The decisions we make and refuse to make long before we die help determine our pathway to the final reckoning. In the movie Little Big Man, the Indian chief Old Lodge Skins says, as he goes into battle, "Today is a good day to die." My mother lived that way, and it allowed her to claim a version of the good death our ancestors prized.

In the early spring of 2009, I discovered that my mother, then 84, could no longer walk far without catching her breath. She had developed two perilously stiff and leaky heart valves. In a pounding rainstorm, I drove her to Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital, where the surgeon told her that if she survived valve replacement surgery, she could live to be 90. Without it, she had a 50-50 chance of dying within two years. My mother weighed the risks of stroke and dementia. Then she said no.

Her later cardiologists were disturbed by her decision, and so was I. But I would later discover that people of my mother's age are often like Humpty Dumpty, seemingly vigorous until a mishap or traumatic surgery sets them on a rapid downward spiral. One of my friends watched her 87-year-old mother die gruesomely after exactly the surgery my mother rejected.

When my mother's "heart failure management" nurse urged me to get her to reconsider, I called and said, "Are you sure? The surgeon said you could live to be 90."

"I don't want to live to be 90," she said.

"I'm going to miss you," I said, weeping. "You are not only my mother. You are my friend."

This was not the world of our ancestors. From the plagues of the Black Death through the 19th century's epidemics of typhoid, childbed fever, and tuberculosis, they helplessly watched people die, from youth to old age. By necessity, they learned how to sit at a deathbed and how to die.

That changed in the 1960s, when doctors and inventors in the U.S. and Europe cobbled together astonishing new medical contraptions, using materials first invented or pressed into military service during World War II -- nylon, Dacron, silicon, plastics.

Dialysis, open heart surgery, CPR, the 911 system, defibrillators, safer surgical techniques, pacemakers -- a whole panoply of lifesaving inventions transformed medical practice and all but abolished natural death. Dying moved from the home to the hospital, obliterating Western death rituals, and changing the way everyone behaved at the deathbed. Dying was transformed from a spiritual ordeal into a technological flail.

Family members were restricted to visiting hours. Often there were no "last words" because the mouths of the dying were stopped with tubes and their minds sunk in chemical twilights to keep them from tearing out the lines that bound them to earth. Months after an ICU death, family members experience high rates of anxiety, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

As this technology spread around the world, it transformed the look of the dying body as well. "When I first started out washing and coffining corpses early in 1965, the majority of cases were home deaths," wrote the Japanese Buddhist mortician Shinmon Aoki. "[The bodies] looked like dried-up shells, the chrysalis from which the cicada had fled ... Along with the economic advances in our country, though, we no longer see these corpses that look like dead trees," he wrote in his memoir, Coffinman. "The corpses that leave the hospital are all plumped up, both arms blackened painfully by needle marks made at transfusion, some with catheters and tubes still dangling. This tells us that our medical facilities leave us no room to think of death."

In the 1400s, a best-selling how-to book called The Art of Dying offered a road map to the deathbed -- framed not as a place of meaningless suffering but as a transcendent battleground where angels and demons struggled for control of the soul. Family and friends gathered at the bedside and recited prescribed prayers, giving the dying person reassurance, faith, and hope. Because we do not have such pathways now, it's no surprise that relatives often panic and insist that "everything be done," even things that are torturous and futile. Any plan seems better than no map at all.

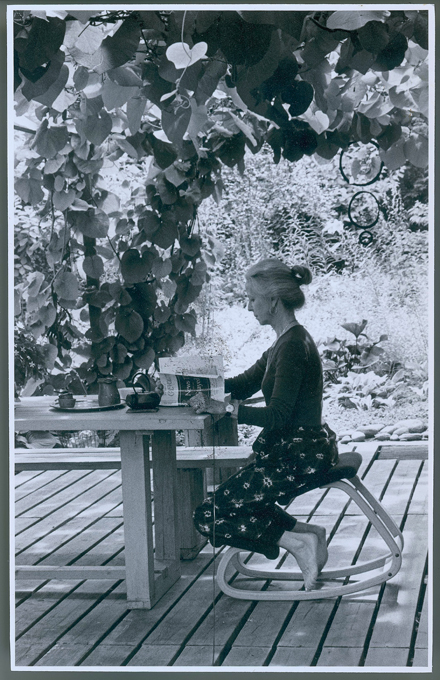

My mother looking very zen and beautiful, a self-portrait, 1980s.

That spring my mother fixed cracked windows in her basement and threw out files for the book my father never finished writing. She told someone she didn't want to leave a mess for her kids. Her chest pain worsened, and her breathlessness grew severe. "I'm aching to garden, to tidy up the neglect of my major achievement," she wrote in her journal. "Without it the place would be so ordinary and dull. But so it goes. ACCEPT ACCEPT ACCEPT."

In July, a new cardiologist suggested inserting an experimental mitral valve replacement, performed by floating the device down a vein. "When I mentioned stroke risk," he wrote in his clinical notes, "she immediately was turned off and did not want to pursue further discussion, again desiring only palliative care."

That August, she had a heart attack. The next day I got a call from yet another cardiologist who had been handed my mother's case. They were preparing her for heart bypass surgery and valve replacement -- the very surgery she had rejected five months before.

She seemed to be heading down the greased chute toward a series of "Hail Mary" surgeries -- risky, painful, and harrowing, each one increasing the chance that her death, when it came, would take place in intensive care. I later discovered that the cost to Medicare would probably have been in the $80,000 to $150,000 range.

Burning with anger, I told the astonished cardiologist that my mother had rejected surgery when she had a far better chance of surviving it, and I saw no reason to subject her to it now. I later found that in a major study, 13 percent of patients over 80 who underwent combined valve and bypass surgeries died in the hospital. In a smaller study, 13 percent died in the hospital and an additional 40 percent were discharged to nursing homes.

I called my mother in the hospital. I said, "I think we're grasping--"

"--at straws," she finished my sentence. She was quiet. "It's hard to give up hope."

Four hours later she called back. "I want you to give my sewing machine to a woman who really sews. It's a Bernina. They don't make them like this anymore. It's all metal, no plastic parts."

"I'm ready to die," she went on. I could barely recognize my stoic and reserved mother. "Cherish Brian," she said, speaking of my long-term partner. "I love Brian. I love Brian for what he's done for you."

My mother came home tethered to a portable oxygen tank. She updated her will. A hospice nurse cut off her long white hair. She took digitalis and squirted morphine under her tongue to manage her intense heart pain.

She pulled out her Japanese ink stone and calligraphy brushes and brushed out a final one-stroke circle, what the Japanese call an enso. Below it she wrote, "For my memorial service."

I was making flight plans when we talked on the phone for the last time. In an outpouring, I told her how I treasured the memory of her ritual teas and regretted not having picked up more of her domestic elegance.

"But Katy," she said, her voice weak. "You're good at other things. There isn't much time."

That night she was taken to the inpatient hospice unit, with one of my brothers following the ambulance. Once settled into her bed, she took off her hammered silver earrings and said to the nurse, "I want to get rid of all the garbage." Naked she had come into the world, and naked she would return. The next morning she told my brother to call his two siblings in California. By the time he got back, she was dead. He broke into sobs.

She died too soon for my taste. But she died the death she chose, not the death anyone else had in mind. Her dying was painful, messy, and imperfect, but that is the uncontrollable nature of dying. I tell you her story that we may begin to create a new Art of Dying for our biotechnical age.

Adapted from Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death, which will be released in paperback June 10. ©2013 by Katherine Anne Butler. Reprinted with permission from Scribner, a Division of Simon and Schuster, Inc.

Join Katy Butler in the "Slow Medicine" group on Facebook.