Two of the world’s biggest banana companies announced Monday that they're joining together to form a banana empire. It's just the latest development in the centuries-long power struggle of the banana world -- an industry dominated by a handful of companies who have strategically muscled out smaller players and exerted outsize control over the countries where they operate.

The new company ChiquitaFyffes, which combines U.S.-based Chiquita with the Irish company Fyffes, the largest banana distributor in Europe, is expected to generate about $4.6 billion in annual revenues and be worth about $1.1 billion.

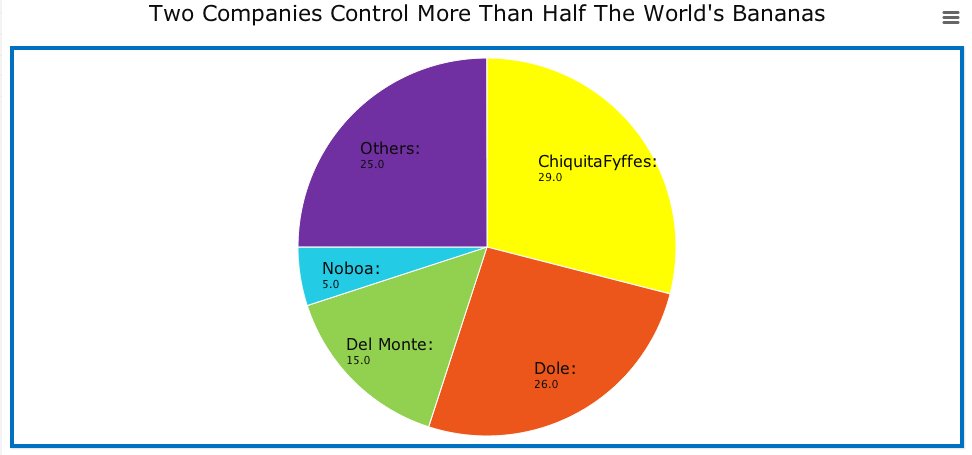

For Chiquita, the move represents an opportunity to do more of what the company has always done: use its leverage to get the best business deals and operate in the most favorable political climate. In addition, the deal means that the already tightly consolidated banana industry is now largely in the hands of just three companies. Chiquita, Dole, Fyffes and Fresh Del Monte Produce control more than 80 percent of the global banana trade, according to the United Nations.

A Chiquita spokeswoman wrote in an email statement to The Huffington Post that Chiquita and Fyffes "share a strong commitment" to growing and selling the best product under good working conditions that are respectful of the environment and "in strict compliance with all applicable laws, consistent with being a good and responsible citizen."

She added that the merger will allow the newly formed company to work with more growers and establish stronger relationships with them.

"Both Chiquita and Fyffes have longstanding relationships with small growers around the world and this merger provides us with even greater capacity to support the industry," the statement reads. "We believe this translates into more opportunities for the customers and consumers we serve, our dedicated employees and our growers and suppliers around the globe."

The graphic below, which is an analysis of 2011 data from BananaLink, a public interest group, shows just how few players there are in the banana business.

"There was a time, certainly in the late 1800s, when there were hundreds of companies in the different aspects of the business," said Steve Striffler, a professor of anthropology at the University of New Orleans. "It didn't really take all that long, maybe a 30- to 40-year period, before there was just a handful of companies."

United Fruit, the predecessor to Chiquita, played a major role in accelerating the consolidation of the industry. It even owned Fyffes at one point, according to Striffler. After opening its doors in 1899, United Fruit quickly realized that to dominate, it would have to take control of every aspect of the banana process.

United Fruit began acquiring land at a fast clip throughout Latin America, ultimately owning about 3 million acres of plantation land, according to Banana Wars: Power, Production and History in the Americas, a volume that Striffler co-edited. At any given time, much of that land was unused, because companies had to relocate their plantations every 10 to 20 years during the early 20th century to avoid diseases and waning soil fertility.

In addition to claiming prodigious amounts of land, United Fruit also expanded infrastructure throughout the region, including railroads and ports. The combination of land ownership and shipping control allowed United Fruit to reach an unprecedented scale and muscle out its competition, ultimately acquiring about 50 percent of the U.S. consumer market, according to Banana Wars.

By the mid-20th century, parts of Latin America were so reliant on banana production that United Fruit and other companies wielded significant political influence in the region. "Those companies -- United Fruit is sort of the most notorious -- had considerable power over local governments," said Striffler. In one of the most infamous examples, United Fruit reportedly convinced U.S. officials to engineer a coup in 1954 to overthrow a democratically elected Guatemalan leader who'd threatened to redistribute the excess land the company had let lie fallow.

"[Chiquita/United Fruit] has had a really nefarious history in all of the areas in which it's operated since its creation," Mark Moberg, a professor of anthropology at University of South Alabama, said of Chiquita. "In Latin America it is referred derisively as 'el pulpo' or 'the octopus.' Certainly nothing about this [merger] is going to improve that. I think it's only going to allow it [to] exert greater leverage."

Today, Chiquita and its rivals exert their influence in subtler ways. Several of the major companies have deals with small, native producers, but their size and scale allow them to essentially dictate the terms of the contracts, Striffler said. Competition between the large banana companies has sometimes helped the smaller growers, according to Moberg, because it would put pressure on the Chiquitas and the Fyffes to offer farmers a better deal out of fear they would go elsewhere.

Now, with so few companies controlling so much of the market, the big players can dictate almost all aspects of their suppliers' production.

"This is kind of like the Walmartization of the banana industry," Moberg said.

By controlling so many aspects of the banana process, ChiquitaFyffes may also be able to raise prices on the fruit, said Dan Koeppel, the author of Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. Banana prices in the United Kingdom, which have nearly halved over the past 10 years thanks to intense supermarket wars, are of particular concern to large banana companies.

"For a century the price of bananas has been kept artificially low," Koeppel said. "Whether it's been through artificial means like starting a war or whether it's grocery stores saying we're going to take a loss on bananas so we can sell other stuff. Consumers have shown themselves to be more tolerant of a higher price banana than we expected. Chiquita, by controlling a big banana distributor, has more control over the price."

The merger will also help Chiquita make inroads into the European market in other ways. Historically, many European countries have insisted that a certain share of their bananas come from their former colonies in the Caribbean, as a way to ensure that the smaller growers that dominate the region don't go out of business. The World Trade Organization ended that quota system in the 2000s, but European countries were still largely favoring Caribbean bananas.

The new merger will likely make it easier to squeeze out those small producers, according to Moberg, who has spent time at family-operated banana farms as part of his research.

"Europe hasn't turned to Chiquita and South America that quickly, and with this merger they're going to have access to that market," said Stiffler. "This is already an industry that is particularly unfair and highly concentrated, [so] it's just one more step in that direction. When you have that extreme of a concentration of ownership and control over an industry, there's something kind of unhealthy about that."