Speaking with Mike Levy, who makes dark, industrial electronic music as Gesaffelstein, is pretty much what you'd expect it to be. In the Frenchman's room at the Standard Hotel, Levy relaxes on the bed in a crisp black shirt, dark pants and sleek shoes, a black scarf draped casually around his neck. He wears glasses that are probably of the style on which Warby Parker based their affordable frames, and the room is dotted with Saint Laurent bags. Everything is either black or white.

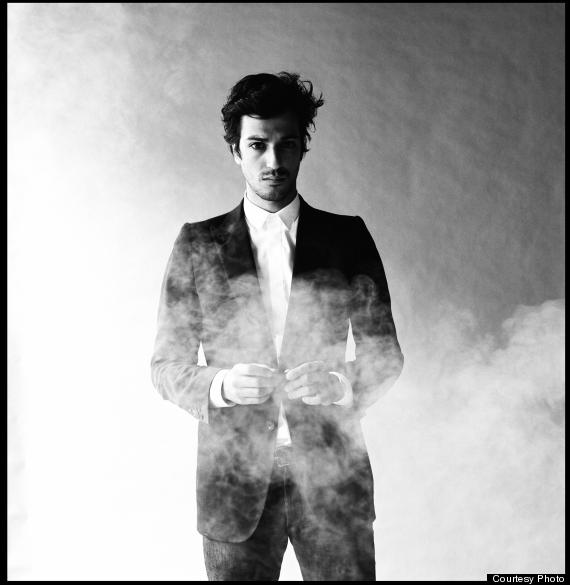

The only really surprising part of meeting and speaking with Levy is that he's actually incredibly warm. The night before, he was performing at Webster Hall, twirling knobs, triggering samples and toying with synths atop a booth with a marble finish. Wearing his customary fitted blazer and white dress shirt, the chain-smoking producer looked like a mad scientist; his dancing wavers on the line between rigidly awkward and endearing.

While he recently scored a bit of a coup by adding synths to "Send It Up" and "Black Skinhead," songs on Kanye West's "Yeezus" album that were co-produced by West, Daft Punk, Brodinski and Mike Dean, the co-sign didn't really translate into Levy's live show. When he interpolated part of "Send It Up" into "Hellifornia," a track off his own recently released album, "Aleph," the crowd didn't seem to notice at all. "I think that it was also hidden in the mix," Levy says. "It wasn't a reaction -- but it's not a radio hit, 'Send It Up.' If you're a big fan of Kanye, you'll be excited, but not otherwise."

Levy joined West in his Paris studio, working on the songs after Daft Punk had already sent in their contribution. "I brought all of my synths to his studio because he would only work in his studio," he recalls, smiling. "So it was a bit complicated."

"I think I got more fans since the Kanye stuff, but it's hard to know if they're from hip-hop or electronic," he adds. "But I got a lot of press in like NME and those stuffs, so I don't know exactly if it's because of Kanye. And I don't want to know, honestly! I can't spend my time thinking about who loves me, where they discovered me."

"Aleph" received great reviews when it was released earlier this year and penetrated far beyond the typical dance music blog circuit. That is itself an accomplishment, in part because Levy's music is so insistently dark and, to the uninterested ear, monotonous. "My music is not synthpop, but there is no pop form -- if you want to make a hit, you don't need to put vocals," Levy offers. "There is no recipe to do a hit. I was not looking to do something pop, but I want to make this music popular. I don't want to do compromises and put my music with a shitty voice or "eeee" sounds. But I think it's interesting to market this album with normal marketing like you would promote a pop album. Because it deserves it -- this music deserves more popularity. I'm not talking about my music, it may be pretentious, but I mean electronic music. Techno music."

For his live sets, Levy does some synth work on the fly and triggers his tracks using Ableton Live. The performances are shorter than DJ sets, with spare lighting and minimal flash. In a recent interview with BBC Radio 1, he described his music as "the opposite of glamor," but that's not entirely true. There is a calculated mystery about Levy, so much so that when I ask him what he did before his four-year-old music career, he puts his fingers to his lips, smiles and replies, "We don't talk about that." There's the designer trappings, the effected hairstyle and aristocratic obsession with subtlety, all of which stand in stark contrast to his Bromance label buddy Louis Brodinski's taste for Southern hip-hop and track jackets.

Of course, Gesaffelstein doesn't find himself mysterious at all. "People think I’m mysterious but I’m not –- that’s just what they think," he told Mixmag earlier this year. "I’m just me. For me the real mystery in electronic music is the artists who try to be cool, when they aren’t cool."

"Gesaffelstein" is a portmanteau of gesamtkunstwerk (German for the perfection of art) and Einstein, who Levy admires. The emphasis on capital-A "art" helps explain why West would be eager to link up with Levy, and it carries into the producer's videos for "Pursuit" and "Hate or Glory." Both visuals were directed by Fleur & Manu, a duo who Levy says "live in my brain." The two videos are extremely different, but united by their art house presentation and the sense that there is a statement living inside each.

"I love cinema, but my favorite thing is music. I can't say that I'm a big fan because for me, if I say I'm a fan, I have to understand everything. Cinema is very complicated -- you have photography, acting, music -- there's a lot of things there," Levy says. "But I think it's important to put a relief between music and video. So we sent a lot of things, like movies, scenes, ambience, music, colors. They came back to me and I was like, "Whoa, that's exactly what I want."

Much ink has been spilled on the "explosion of electronic dance music in the United States," but a number of French producers are winkingly cashing in on the phenomenon while holding most "EDM" music -- and its fans -- in low regard. Acts like Justice, Kavinsky and even Daft Punk are experiencing revivals that are amplified in scale because of the interest of American audiences in entirely different music. Like Justice, Kavinsky and Daft Punk, Levy makes music that is wholly unrelated to the progressive house sounds that Dutch DJs like Tiesto and Afrojack play when they headline festivals.

"I have the feeling that [in the U.S.] they don't really grant a big difference between Daft Punk, David Guetta and me," Levy says. "In the U.S., it's 'EDM' because it's electronic. But it's not the same -- if I play in Europe at a festival, I know for sure that I will not play at the same stage as David Guetta. It's totally different, and the crowd too. Most of the time when I play in Europe, I'll play in an alternative festival, with a rock band, a hip-hop group or even just an electronic festival with only European techno. For us, in France, 'EDM' is not 'electronic' -- it's just dance music, but in the worst way. There is nothing electronic, there is nothing techno, there is nothing house. It's just not the same music."

That artists like Levy are able to play medium to large rooms around the States is not without its awkward moments. A number of fans at Webster Hall seemed to be expecting festival dance music, arriving in tank tops and using rave gloves to visually overstimulate fellow concertgoers. Whether they were disappointed by Gesaffelstein's spare visuals and subtle set or enamored by his quirkiness is the question that will ultimately determine whether dance music is to once again drift from the forefront of America's music culture. Nothing as popular as the frenzied drops which now underpin hits for Rihanna, Taylor Swift and Lady Gaga will be relevant forever -- it is artists like Levy who, if they're able to cultivate audiences of a critical mass, will be left when the major labels start chasing another sonic trend.