By: Steve Silver, Esq., Partner at TheLegalBlitz.com

This is only a portion of the article. To read the complete article, please CLICK HERE.

Attending a professional sporting event carries some inherent risks. Balls, equipment, and even athletes themselves sometimes fly into the stands. Drunken idiots throw punches. Mascots can sometimes get a little handsy. Dangerous weather can roll in. And now, hot dogs and t-shirts are routinely shot out of guns, cannons, and slingshots, adding to the extensive list of things that can hurt you at a game.

What happens, though, when a flying object, such as a hotdog, that is not an inherent part of the game, injures a spectator? The answer, much like the state of sporting event tort law in this nation, is not so clear. But the Missouri Supreme Court is about to revisit the so-called "baseball rule" of tort law to determine what duties, if any, teams owe to spectators.

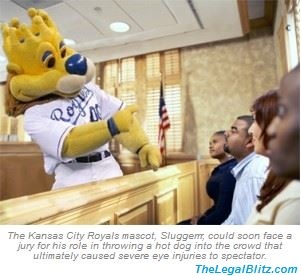

In a bizarre case arising out of an errant hot dog at a Kansas City Royals game, one plaintiff is seeking to expand the remedies available to injured spectators. John Croomer of Overland Park, Kansas says he was injured at a 2009 Royals game when the team's mascot, Sluggerr, threw a four ounce, foil-wrapped hot dog into the stands that struck him in the eye. Croomer had to have two eye surgeries and now has permanently impaired vision. Croomer alleges that he incurred nearly $5,000 in medical costs and is seeking an award of more than $20,000.

The Jackson County jurors who first heard the case two years ago sided with the Royals, saying Croomer was completely at fault for his injury because he wasn't aware of what was going on around him. An appeals court overturned that decision in January, ruling that while being struck by a baseball is an inherent risk fans assume at games, being hit with a hot dog is not. The state Supreme Court heard oral arguments last month, but didn't indicate when it might issue its ruling.

Croomer's case presents the Missouri Supreme Court with a unique opportunity to address the legal duty both the Royals and its mascot owes to fans, which is why it could have monumental ramifications for other team and stadium owners throughout the country.

The issue at the heart of this case is how the Baseball Rule applies to mascots. But what exactly is the Baseball Rule?

As the Supreme Court of New Mexico summarized in extensive detail in Edward C. v. City of Albuquerque (2010), around the 1880s, the rules of baseball evolved to the point where pitchers threw overhand, catchers wore masks and chest protectors, and the grandstand area behind home plate became known as the "slaughter pen," apparently because of the frequent injuries suffered by spectators watching the game from that area. It was not until 1879 that the first professional team, the Providence Grays, installed a screen behind home plate for the express purpose of protecting spectators.

However, the limited protective screening behind home plate failed to eliminate spectator injuries and did not curtail burgeoning plaintiffs' claims. As a result, more baseball spectator injury cases came under appellate review, and courts responded by developing a baseball-specific jurisprudence. Courts almost universally adopted some form of what is known as the "baseball rule," creating on the part of ball park owners and occupants only a limited duty of care toward baseball spectators. In its most limited form, the baseball rule holds:

that where a proprietor of a ball park furnishes screening for the area of the field behind home plate where the danger of being struck by a ball is the greatest and that screening is of sufficient extent to provide adequate protection for as many spectators as may reasonably be expected to desire such seating in the course of an ordinary game, the proprietor fulfills the duty of care imposed by law and, therefore, cannot be liable in negligence.

Akins v. Glens Falls City Sch. Dist. (1981). Nearly from the outset, courts recognized a baseball rule as a necessary divergence from the prevailing "high degree of care for ... safety" that is owed to business invitees, given the nature of the game and the relationship between the spectator and the stadium owner or occupant. Wells v. Minneapolis Baseball & Athletic Ass'n (1913). The Wells court held that "[T]his [business invitee] rule must be modified when applied to an exhibition or game which is necessarily accompanied with some risk to the spectators. Baseball is not free from danger to those witnessing the game. But the perils are not so imminent that due care on the part of the management requires all the spectators to be screened in." Id.

In limiting the duty, courts have also reasoned that "a large part of those who attend prefer to sit where no screen obscures the view" and owners or occupants have "a right to cater to their desires." Id.

This is only a portion of the article. To continue reading the complete article, please CLICK HERE.

Managed by active attorneys, TheLegalBlitz.com is a website dedicated to tackling the toughest sports law issues. Our mission is to frame all aspects of athletics - including but not limited to competition, contracts, agents, media & technology, marketing & sponsorships, franchises & stadiums, economics, communications, and labor relations - in the context of law through a forum that everyone can enjoy and learn.