Recently, the children at P.S. 261 in Brooklyn were turned loose on the new playground at their school in the Boerum Hill neighborhood. And it was an instant hit, with swarms of kids running and playing.

What the kids didn't know is that their playground is the first completely "green" school playground in New York City, the first of 40 such playgrounds which will be built in the city using the principles of "green infrastructure." When it rains, the runoff will go into rain gardens and linear tree pits, rather than nearby gutters and streets.

The program announced last week is similar to recent work in Philadelphia, which was described in last week's installment. In New York, the NYC Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) is providing "Green Infrastructure" money and the Department of Education (DOE) is joining with private donors to allow The Trust for Public Land (TPL) transform poorly functioning, part-time schoolyards into attractive, multi-functional, full-time playgrounds, of which P.S. 261 was the first.

As children gamboled on the new synthetic turf field that, along with other design elements acts like a sponge to help soak up storm runoff that would otherwise overload the sewers, the leaders of the two agencies and the local City Council member cut the green ribbon signifying completion of the first truly "green" school playground in New York. The landscape design firm Siteworks partners with TPL to manage a three-month community design process at each site, then works to create plans that direct storm water runoff into rain gardens and linear tree pits; water is also collected using porous pavers and in the playing fields that were once hot, crumbing, dangerous asphalt. And each site is designed to collect the first inch of rain water from every storm, which covers most typical rain events.

Ribbon cutting at P.S. 261

Kids playing in the newly renovated playground at P.S. 261

The new garden at P.S. 261

Green infrastructure is a technical term, first coined in the 1990s, which generally involves design and construction emphasizing the use of natural components. There are a variety of definitions, but generally, in the context of small urban spaces, it means "green" roofs, porous pavement, planted areas -- known as "rain gardens" -- designed to absorb runoff, and the like.

In Philadelphia, where Mayor Michael Nutter and his team have put forward perhaps the nation's most ambitious and complex plan for a "green" city, the Trust for Public Land is working with city officials (as described last week) to transform traditional asphalt schoolyards and old-fashioned playgrounds into "green playgrounds." Philadelphia is also adding a range of GI elements to parks including, for example, a subsurface infiltration bed beneath a new basketball court at Clark Park to manage storm water runoff on site, as well as from an adjacent street and parking lot and a storm water wetland in Fairmont Park. Using a combination of public funds (including a significant contribution from the Philadelphia Water Department) and private donations, the projects create neighborhood amenities that improve the community, expand opportunities for exercise and fitness, and also capture storm water runoff to help Philadelphia meet its ambitious goals for cleaning the adjacent Delaware and Schuylkill rivers.

P.S. 261 playground before renovation

P.S. 261 playground after renovation

No open space is too small to contribute environmental value. In a perfect evocation of ecologist Rene Dubos' admonition to "Think globally, act locally," New York City DEP allocated funding to the Parks Department to transform striped and paved traffic islands into "Greenstreets." The idea of turning formerly paved areas into small gardens is not new. Approximately 2,000 of these esthetically pleasing transformations were effected over the course of two decades, but the latest GI spin has the Greenstreets being designed to capture the storm water from the surrounding streets in specially designed systems, which include lush planting beds with plants that can tolerate both inundation and drought, along with the other indignities of urban street life, such as salt, contaminants, and dog waste.

These hyper-performing landscapes are tiny by park standards, but they bring beauty to formerly barren corners, serve as mini habitats for insects and birds, and most of all, soak up storm water. Moreover, these steps are only the beginning of efforts to abate the increasing "heat island effect" that global warming is bringing to our nation's cities. During Hurricane Irene two years ago, one of the first generation GI Greenstreets captured 25,000 gallons of storm water, and a corner notorious for flooding in normal storms didn't flood.

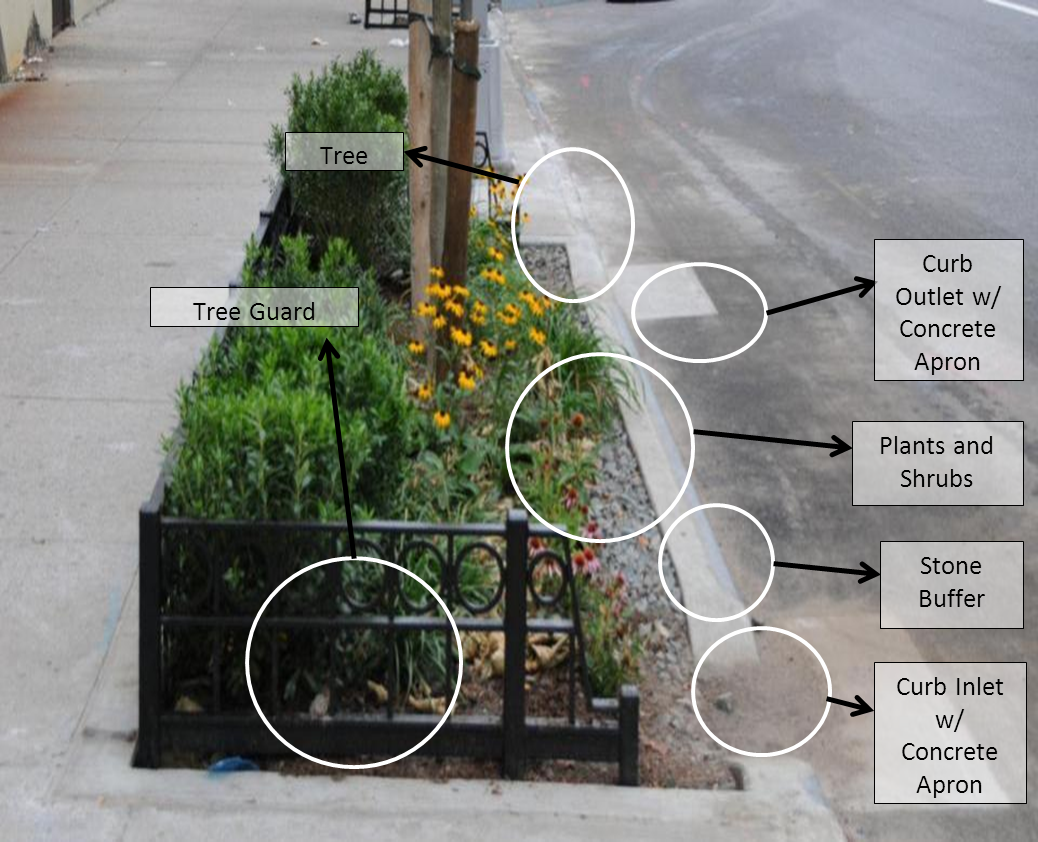

The NYC DEP is also working with Parks and Transportation Departments to turn the humble street tree planting pit into a "Right of Way Street Tree Bioswale." These planting beds are much larger than normal, five feet by twenty feet, and ten feet deep, with structured soil and drainage materials and infrastructure, with a tree in the middle, and a variety of shrubs and ground covers. Inlets from the street usher in the storm water from the curb, and each bioswales is designed to capture 3,000 gallons of water per rain event.

Diagram of Street Tree Bioswale. Image Credit to New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

The same Street Tree Bioswale in flooded condition. Image Credit to New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

Best of all, perhaps, the DEP is also paying the Parks Department crews that maintain both the Greenstreets and Street Tree Bioswales, addressing one of the essential reasons -- chronic lack of maintenance money -- why many city park systems don't embark on creating new parks and public spaces, no matter how small. But other cities across the country are investing in both new parks that capture storm water and retrofitting existing parks to provide recreational space for humans, habitat for animals and plants, and crucial storm water absorption, as will be explored in my third posting on this topic next week.

A longer version of this article was originally published in "The Nature of Cities" blog. Marianna Koval, a consultant for the Trust for Public Land, provided research on the use of Green Infrastructure in parks, some of which is incorporated in this piece. Additional assistance was provided by Cecille Bernstein, also of The Trust for Public Land.