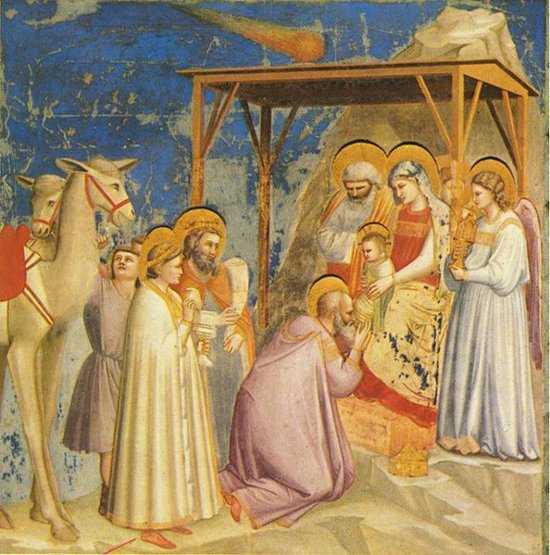

The heavens have always been a source of inspiration for poetry, music and the visual arts. The first chapter of the biblical book of Genesis already talks about the creation of the Sun, Moon and the stars. The ancient Babylonian, Chinese, North European and Central American cultures all left records and artifacts related to various astronomical observations. It was only natural then, that at the end of Medieval times, with the first signs of the Renaissance (in the 14th and early 15th centuries), the heavens would start making an appearance in important works of art. One impressive demonstration of the interest in astronomy was in the great, Italian painter Giotto di Bondone's fresco Adoration of the Magi (Figure 1). The fresco was painted around 1305–06, and it features a very realistic depiction of a comet, representing the "Star of Bethlehem." It is thought that the comet's image was inspired by Giotto's observations of Halley's Comet in 1301.

Figure 1. The Adoration of the Magi by Giotto di Bondone. From: Wikimedia Commons.

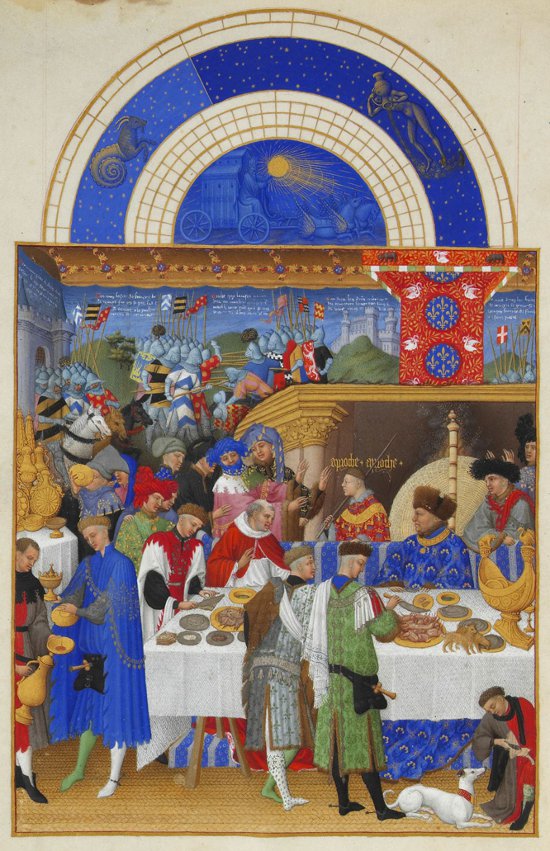

A second beautiful example of astronomy in art is provided by a famous illuminated manuscript. The three Dutch miniature painters known as the Limburg brothers created the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry book of prayers (Book of Hours), and it is currently considered to be one of the most valuable books in the world. The book was unfinished at the time of the death of the three brothers in 1416, and the work on it was completed by the painters Barthélemy van Eyck (possibly) and Jean Colombe (certainly). As Figure 2 shows, an attempt was clearly made to give an accurate representation of the night's sky, even including meteors.

Figure 2. Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry by the Limburg brothers. From: Wikimedia Commons.

A third magnificent painting, the The Battle of Issus, by the German painter Albrecht Altdorfer (Figure 3), may be the first painting in which the curvature of the Earth is shown as seen from above, from a great height.

Figure 3. The Battle of Issus by Albrecht Altdorfer. From: Wikimedia Commons.

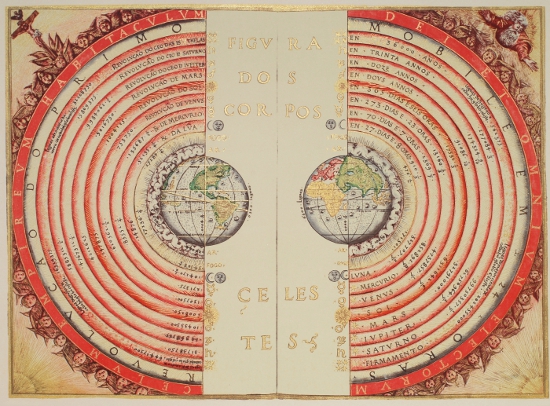

Finally, I find the illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric model by the Portugese cosmographer Bartolomeo Velho (Figure 4) extremely attractive. The illuminated illustration, Figure of the Heavenly Bodies, was created in France in 1568.

Figure 4. Figure of the Heavenly Bodies by Bartolomeo Velho. From Wikimedia Commons.

All of these works of art were being created shortly before or at a time when the Copernican revolution was about to forever change the view humans had of the cosmos and on their place within it. Far from being perfect and immutable, the heavens turned out to be part of an ever-evolving universe.