The Attorneys General of New York and Vermont have joined the fight against California's San Onofre nuclear power plant in an effort to stop federal regulators from erasing all record of a judicial ruling that the public has a right to intervene before major amendments are granted to an operating license.

If the five-member Nuclear Regulatory Commission grants the request of their staff to vacate the ruling of the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board and expunge the record, it will eliminate a precedent that affects power plant operations and regulatory practices around the country. In particular, it will affect the six-year fight in New York to shut the Indian Point power plants 25 miles north of New York City; and Vermont's ongoing effort to shut the Vermont Yankee power plant.

If the five-member Nuclear Regulatory Commission grants the request of their staff to vacate the ruling of the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board and expunge the record, it will eliminate a precedent that affects power plant operations and regulatory practices around the country. In particular, it will affect the six-year fight in New York to shut the Indian Point power plants 25 miles north of New York City; and Vermont's ongoing effort to shut the Vermont Yankee power plant.

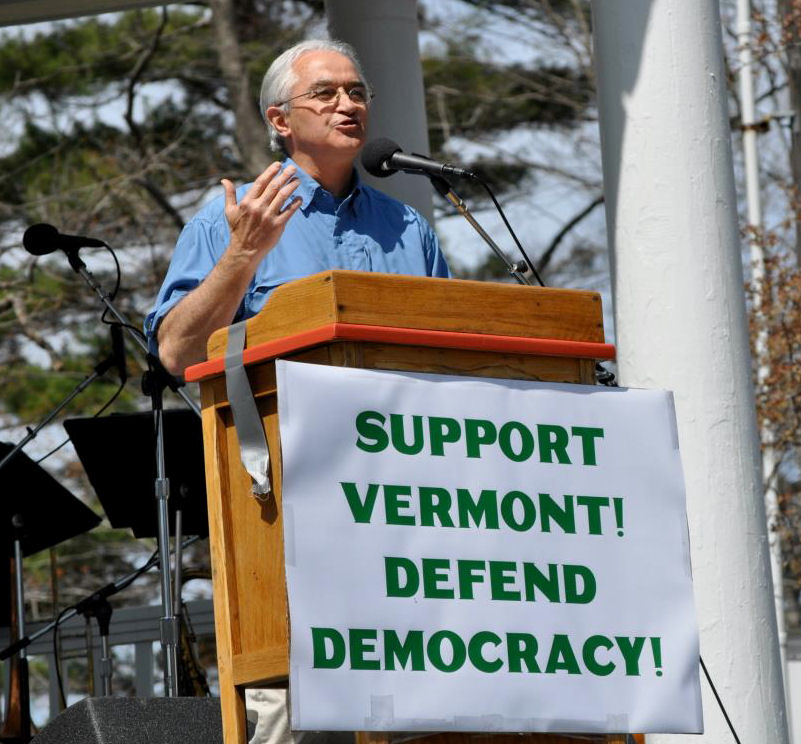

The cross-country battle now being waged by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and Vermont Attorney General William Sorrell is an uphill fight against one of the most powerful professional staffs in the US government and an agency that has a unique view of its own independence.

"The Commission has stated that it is not bound by judicial practice, including that of the United States Supreme Court," stated Schneiderman and Sorrell in a brief filed June 24 with the NRC challenging the staff request.

"The Commission has stated that it is not bound by judicial practice, including that of the United States Supreme Court," stated Schneiderman and Sorrell in a brief filed June 24 with the NRC challenging the staff request.

In practice, the NRC has taken the position that U.S. Supreme Court decisions on procedural rules that apply to federal judicial proceedings are advisory, and the Commissioners are not bound to follow them. That position creates difficulties for civic groups, environmental organizations, or states seeking to challenge the operation of local nuclear power plants before the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board, the NRC's judicial review body.

"Four years ago," said David Lochbaum of the Union of Concerned Scientists, "an ASLB in California ruled against the staff in a challenge to the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant. The staff opposed requiring the plant to assess the possible impact of a deliberate commercial jet crash into the plant, saying it was speculative. The board ruled that since there have been terrorist attacks using commercial jets, that the challenge was not speculative and should be allowed.

"The Commissioners then ruled that the Board's decision applied only to Diablo Canyon and could not be applied to anyplace else. If they had won that case, I'm sure they would have said it was a precedent and used it everywhere. But since they lost, they made it unique."

"The Commissioners then ruled that the Board's decision applied only to Diablo Canyon and could not be applied to anyplace else. If they had won that case, I'm sure they would have said it was a precedent and used it everywhere. But since they lost, they made it unique."

It is the issue of hiding loses before a judicial tribunal by the NRC staff and then forcing states and civic groups to litigate the same issue at each and every power plant that has drawn fire from Sorrell and Schneiderman.

Sore Losers

The fight at San Onofre, in which the Board ruled decisively against the NRC staff, was over the most contentious issue in nuclear power regulation: the ability of the staff to bypass federal laws by permitting "de facto" amendments to the plant's operating license.

The regulatory process for nuclear power plants is extraordinarily exacting. The operating license contains the exact "design basis" blueprints for the reactor and every safety and support system. It also delineates the maintenance schedule and types of procedures used to assure that critical systems function effectively over decades of intense use despite high pressures, intense heat, and concentrated radiation.

"Congress has commanded that licensees may not, under penalty of law, deviate from the terms of their reactor operating licenses," stated the ASLB in their decision against San Onofre and the NRC staff.

That strict provision is not a mindless bureaucratic intrusion. Should anything go wrong in a system at a nuclear plant at any time, staff or inspectors should be able to go immediately to the license blueprints and support documents to check on the last known condition of that system and its expected behavior under various stresses. If the actual systems differ markedly from the license blueprints staff could not, in an emergency, quickly pinpoint what is going wrong since there would be no way to know what a properly working system should look like.

For that reason, any change to the license's "design basis documents" is a major production. The NRC staff has, at times, granted changes to licenses through the issuance of Confirmatory Action Letters, which recognize and approve these license alterations.

But by issuing the CALs, the NRC staff bypasses a series of agency regulations and federal laws mandating the involvement of the public by posting the proposed license change in the federal register, soliciting comments, and holding formal public hearings. The use of the CAL alternative is not intended to run roughshod over the law and public participation. It is intended to allow for minor changes and updates which recognize improvements in technology - like upgrading from manually operated to powered seats in a car - but are not significantly different.

Risky Business

The fight at San Onofre, however, stemmed from the use of the CAL process to allow Southern California Electric to design an entirely new and different type of steam generator and, when it failed, to run the defective generators at just 70% strength, using an experimental program. SCE did not know if the plan would work, but the company and NRC staffs were confident the equipment could be closely monitored to prevent a disastrous loss of coolant accident.

Steam generators are massive, 85-foot-tall, heat exchange systems which cycle the superheated, radioactive, pressurized water from the core of the nuclear reactor through nearly 10,000, thin tubes and then back into the reactor ( http://bit.ly/11pcbIk ). Clean, uncontaminated water flows over these tubes, instantly boils and turns to steam, which then drives the massive turbines that generate electricity. If the tubes fail, pressurized radioactive reactor water escapes, and this could lead to loss of reactor coolant and a meltdown - the most serious type of nuclear accident.

Tubes in the newly designed steam generators at the two San Onofre power plants began failing at an alarming rate because of unexpected vibrations which banged the tubes together. It was a situation which had never been encountered, and it was only a theory that the generators could safely operate at reduced power.

Despite the novelty of the proposal and the uniqueness of the problem, the NRC staff and SCE insisted that the changes were minor. That position was challenged by Friends of the Earth and the Natural Resources Defense Council, asserting that such changes required a formal license amendment with public hearings.

The ASLB agreed, stating the proposed operating plan for the damaged equipment "is a radical deviation" from the plant's design basis documents which, "if implemented... would grant SCE authority to operate beyond the scope of its existing license..."

Rather than go through public hearings about the safety of the new steam generators, SCE decided to permanently shut San Onofre.

But the NRC was not content to lose.

"The ASLB ruling is very critical of the way the NRC staff has handled the regulatory process," said Damon Moglen, director of the Climate and Energy Program at Friends of the Earth. "One of the implications of the ruling, other than their hurt egos, is that the NRC staff's power to make significant judgments about reactor safety is limited.

"And according to their way of seeing the world, it means proscribing the staff's ability to make serious decisions in-house. In this case, it means outside of public view, outside of public involvement, and outside of public adjudicatory proceedings."

Continue Reading at Energy Matters.