Emerging markets are driving global growth, and 3.5 billion people are moving to cities. That's $20 trillion of infrastructure to lay down. It's either a big problem or an opportunity. -- Peter Henry, dean of NYU's Stern School of Business, New York Times Magazine.

Global investors have focused on the opportunities offered by urbanization in emerging markets. But some observers have begun to imagine the potential negative effects of billions of unskilled people moving from rural areas to already polluted cities, pushing groaning infrastructures to their limits.

In fact, in almost all post-apocalyptic visions of the end of civilization, earth's remaining inhabitants struggle to survive in the countryside, outside of destroyed, dangerous, or smoldering urban areas. There is good reason to worry about the sheer density of modern megacities when faced with threats such as nuclear catastrophe, acts of war and terrorism, disease, pollution, or simply a lack of critical natural resources such as water and clean energy. Today, half the world's population lives in cities that take up only 2.7 percent of the earth's available land. Yet in spite of potential threats and bottlenecks, the pull of urbanization has been so compelling that for the past 100 years rural-urban migration been recognized as a major component of world GDP growth. In emerging countries, urbanization rates are often used to measure relative stages of economic development.

Art by Richard George Davis

Art by Richard George Davis

Name and Population1 Beijing, China -- 672,0002 Vijayanagar, India -- 500,0003 Cairo, Egypt -- 400,0004 Hangzhou, China -- 250,0005 Tabriz, Iran -- 250,0006 Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey -- 200,0007 Gaur, India -- 200,0008 Paris, France -- 185,0009 Guangzhou, China -- 150,00010 Nanjing, China -- 147,000

Source: Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census by Tertius Chandler. 1987, St. David's University PressSource: Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census by Tertius Chandler. 1987, St. David’s University Press

Although investors might dream of construction cranes and new New Yorks being built weekly, governments in developing countries are now warning that the flood of new urban citizens must be slowed. Uzbekistan, North Korea, and a host of African countries are attempting to slow their rates of urbanization. Circular, or reverse migration has in fact occurred in some parts of Africa already. According to IRIN, a UN news agency:

"Twenty years ago, South Africa's cities were braced for a massive influx of rural migrants following the scrapping of apartheid-era pass laws which had restricted black people's movements. Cities such a Johannesburg and Durban have indeed grown, but not at the phenomenal rates projected and others have hardly grown at all.

According to Deborah Potts, a reader in human geography at King's College London, similar patters of circular migration are playing out in many African countries, countering the effects of rural-urban migration and confounding the widely held assumption that the continent is urbanizing rapidly."

In other countries, urbanization is accelerating, but at a harmful pace. Pakistan is an extreme example of urban dysfunction and inadequate infrastructure. Its projected urban growth rate is the highest in the world, and is set to increase from 75 million to 200 million by 2050. Currently, half of the people living in its cities live in slums. At the same time, Pakistan's rural population will increase from 175 to 325 million. How is this possibly sustainable in one of the poorest and most politically unstable countries on earth? Given the dangers, who will dare to invest in and build its infrastructure? How can these new megacities afford the energy they will need to support this level of population growth, to name just one resource?  Yale Press has published a new book, The Very Hungry City that focuses on the energy and resource requirements of modern cities. The author, Austin Troy, lives in Vermont, which is the East Coast center of the green movement in the United States. Prof. Troy is an expert in spatial analysis and in using GIS (Geographic Information Systems) in order to understand urbanization and the urban environment. He uses these tools to analyze energy use in cities, something he calls 'urban energy metabolism'. The most compelling conclusion of the book is that there is a 'sweet spot' of urban development, an optimal mix of various services including public transportation and energy, which together create a benign state of economic efficiency as well as a smaller carbon footprint. Obviously, achieving such a state requires intelligent policies, and I believe that Prof. Troy is correct to focus on best practices. Urban planning is not just a matter of targeting optimal population size. At the heart of optimal development there has to be optimal information. Size doesn't really matter, data, in conjunction with a stable political system that can effectively utilize this information, does. The cities that are able to do this will thrive, those that cannot will not be able to compete. According to Troy:

Yale Press has published a new book, The Very Hungry City that focuses on the energy and resource requirements of modern cities. The author, Austin Troy, lives in Vermont, which is the East Coast center of the green movement in the United States. Prof. Troy is an expert in spatial analysis and in using GIS (Geographic Information Systems) in order to understand urbanization and the urban environment. He uses these tools to analyze energy use in cities, something he calls 'urban energy metabolism'. The most compelling conclusion of the book is that there is a 'sweet spot' of urban development, an optimal mix of various services including public transportation and energy, which together create a benign state of economic efficiency as well as a smaller carbon footprint. Obviously, achieving such a state requires intelligent policies, and I believe that Prof. Troy is correct to focus on best practices. Urban planning is not just a matter of targeting optimal population size. At the heart of optimal development there has to be optimal information. Size doesn't really matter, data, in conjunction with a stable political system that can effectively utilize this information, does. The cities that are able to do this will thrive, those that cannot will not be able to compete. According to Troy:

"... I believe that communities committed to restructuring themselves for energy efficiency will be at a big advantage over those that do not. If changes are put in place correctly, they will also make cities more desirable, vibrant, aesthetic, and healthy places to live."

I hope that Pakistan's leaders read Prof. Troy's book. There is a wealth of academic literature on cities they should be adding to their libraries. Cities are central to all major civilizations, beginning with Ur in Mesopotamia, and now the megacities (a la Blade Runner) that are challenging national governments. But according to Brendan O'Flaherty, author of City Economics, "one of the oldest reasons cities were built: military protection" perhaps no longer applies. In fact, dense populations and their interconnecting transportation systems are the key target of terrorist groups. Cities can no longer be protected by a wall -- as were the ancient cities of Beijing and Baghdad. Their purposes and relative advantages have changed. One could argue that the key threat to cities today is internal -- overpopulation. A world where population growth is highest where poverty is greatest is not a recipe for peaceful and prosperous cities.However, this growth could be slowing faster than anticipated.

I hope that Pakistan's leaders read Prof. Troy's book. There is a wealth of academic literature on cities they should be adding to their libraries. Cities are central to all major civilizations, beginning with Ur in Mesopotamia, and now the megacities (a la Blade Runner) that are challenging national governments. But according to Brendan O'Flaherty, author of City Economics, "one of the oldest reasons cities were built: military protection" perhaps no longer applies. In fact, dense populations and their interconnecting transportation systems are the key target of terrorist groups. Cities can no longer be protected by a wall -- as were the ancient cities of Beijing and Baghdad. Their purposes and relative advantages have changed. One could argue that the key threat to cities today is internal -- overpopulation. A world where population growth is highest where poverty is greatest is not a recipe for peaceful and prosperous cities.However, this growth could be slowing faster than anticipated.

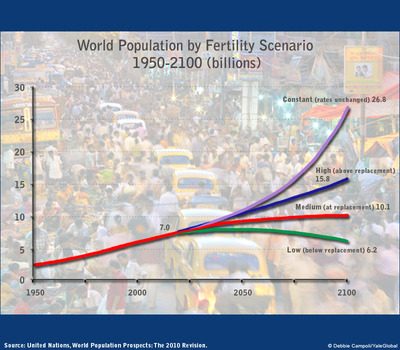

Moving beyond 2050, the population scenario could change radically. This is critical because the urbanization narrative depends on an expanding population. The United Nations projects world population figures for 2100 to be as great as 15 billion, if present fertility rates are maintained. But this is doubtful. According to Joseph Chamie, former director of the United Nations Population Division writing for YaleGlobal Online:

The demographic patterns observed throughout Europe, East Asia and numerous other places during the past half century as well as the continuing decline in birth rates in other nations strongly points to one conclusion: The downward global trend in fertility may likely converge to below replacement levels during this century. The implications of such a change in the assumptions regarding future fertility, affecting as it will consumption of food and energy, would be far reaching for climate change, biodiversity, the environment, water supplies and international migration. Most notably, the world population could peak sooner and begin declining well below the 10 billion currently projected for the rest of the 21st century. -- "Global Population of 10 Billion by 2100? - Not So Fast"

For a variety of reasons, urbanization itself results in falling fertility rates. People who live in cities have fewer children than those who live in the country. And once fertility rates fall, there is no example of them rebounding above replacement levels, even in rich countries. In poorer countries, such as Afghanistan, the cry to educate women is to me a euphemism for controlling birthrates, since this is the invariable effect.

Urbanization is a certainly a major developmental issue, and whether or not there are multiple models remains to be seen. One theory out forward by J Vernon Henderson, a professor at Brown University, is that high urban concentrations are useful at first, but as cities mature economic activity needs to be dispersed more widely to prevent overconcentration of negative effects such as pollution and traffic. Whether or not cities can make this transition depends in large part on the strength of their governance and sound fiscal management.

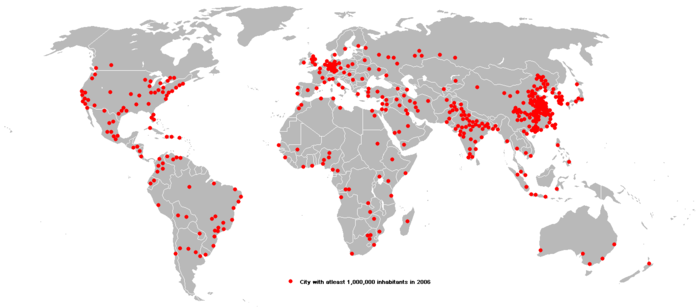

CITIES WITH INHABITANTS OF AT LEAST ONE MILLION PEOPLE IN 2006

Increased urbanization is an integral part of economic growth. However, over the past several decades, many observers have argued that in the context of developing world, there has been an unhealthy focus of growth in very large, dominant cities, which are known as "primate cities." In particular it is noted that in many developing countries, the largest city is disproportionatelylarge in comparison to the rest of the distribution of city sizes. This size discrepancy is believed to result from superior provision of public goods and opportunities for rent seeking. -- "Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space"

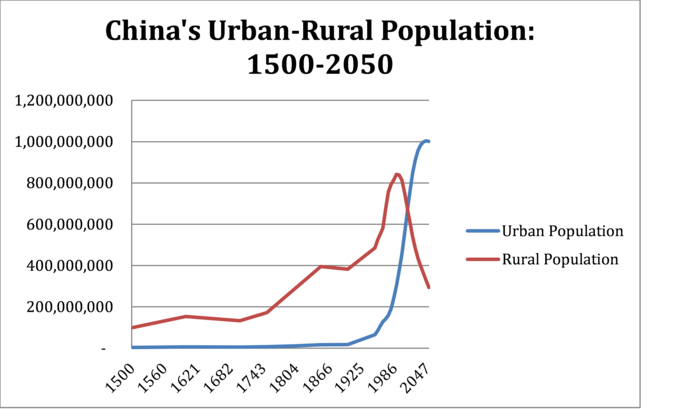

China's population will peak in another dozen years or so. As of last year, half of its citizens live in cities. India will not reach its peak population for another 35 years. These two huge and dynamic countries will face daunting challenges in order to provide food, water, energy and essential services such as transportation to their urban inhabitants. Central and South America are already highly urbanized, as is of course North America, Europe and Australia. If Africa slows, with a global population peak within sight in this century, will we also see peak urbanization? The implications for the growth of the global economy are profound.

For the past twenty years, the explosive growth of China's cities has been seen as the blueprint for other developing nations. But it seems that China's new leadership team is hedging its bets and rethinking the urban-rural mix. According to Premier Li Keqiang this week:

In the course of urbanization, those farmers who want to migrate to cities can engage themselves in secondary and tertiary industries, and for those who want to stay in the villages, they can be engaged in farming operations of an appropriate scale. In both ways they can make money and enrich themselves.

To be a rich farmer it seems, might also be glorious.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog. What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog. What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.