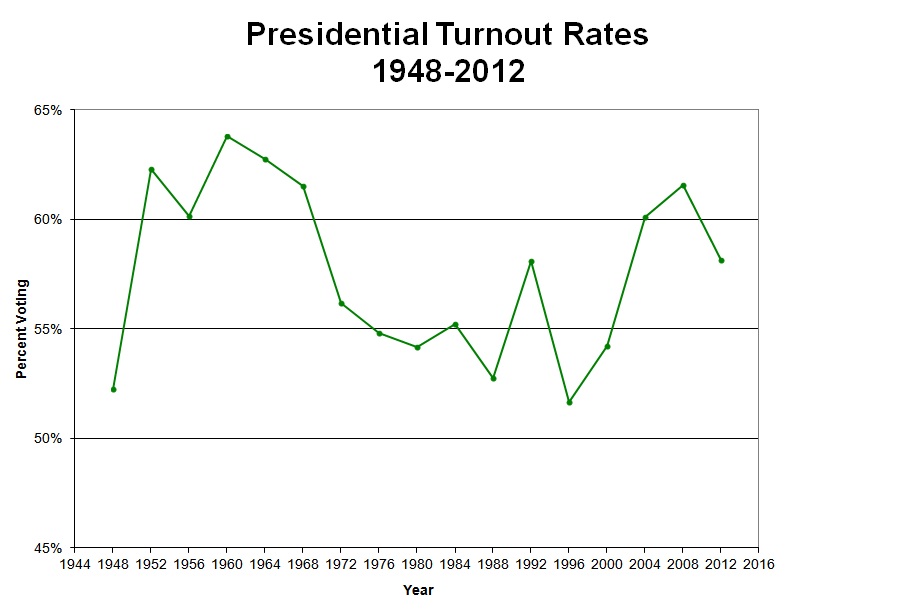

The reelection of Barack Obama was tarnished by a lower voter turnout rate than 2008, dropping from 61.6% of those eligible to vote to 58.2%, or a decrease of 3.4 percentage points. Here, I place the 2012 turnout rate in historical perspective and analyze where turnout decreased, and where it increased. These turnout patterns illuminate how participation is stimulated in battleground states, how much the devastation of Hurricane Sandy depressed turnout, and provide insights to the much-discussed rise in the minority share of the electorate.

The Big Picture

The 2012 election is placed in recent historical perspective in the graph below, which plots from 1948 to 2012 presidential turnout rates for those eligible to vote. From this perspective, the decline since 2008 is not alarming. Modern second term presidents successfully seeking reelection most often experience a participation decline. The only post-World War II presidents who enjoyed a turnout increase were Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama combined for an average 4.3 percentage point drop in voter participation from their first election to their second.

Perhaps a turnout decline is to be expected for successfully reelected presidents. Presidents who fail to win reelection are defeated when a majority of citizens desire a new direction for the country, while citizens approve the job performance of those who win reelection. It is easier to mobilize people against than to approve a political figure. The two modern presidents who sought reelection and failed were Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush. The 1980 election saw a slight 0.6 percentage point turnout decline from 1976 and the 1992 election saw a dramatic 5.3 percentage point increase from 1988. (Gerald Ford also sought election, but did not formally seek reelection in his role of replacing Richard Nixon following the resignation.)

Furthermore, while the turnout rate declined in 2012, participation did not experience a wholesale collapse. The 2012 turnout rate is higher than all turnout rates from 1972 to 2000, a time when pundits and academics alike lamented a decline in voter turnout. The 2012 turnout rate of 58.2% is just slightly higher than the 1992 rate of 58.1%, arguably one of the more exciting recent elections due to the uncertainty surrounding the three-way race between George H.W. Bush, Ross Perot and Bill Clinton. Despite a dip in the road, American citizens continue to be politically engaged.

Minnesota led the states, again, with a turnout rate of 75.7%. Hawai'i was again the laggard, with a turnout rate of 44.2%. These two states are perennially in their respective positions. Minnesota puts voters first with voter-friendly policies known to increase turnout, such as Election Day registration. Perhaps Hawai'i can be forgiven for its poor showing since the state is far from the mainland: it rarely gets any attention from the presidential campaigns and many potential voters know who the presidential winner is before their polls close.

The Value of the Battleground

Voters in three states, plus the District of Columbia, were actually more engaged than 2008, albeit with a increase of less than a percentage point. Putting DC aside for a moment, these three states were Iowa, Nevada, and Wisconsin. An obvious commonality is that all three are 2012 battleground states. Indeed, voter participation in every battleground state declined less than the national average. The exception is Pennsylvania, although only the Romney campaign belatedly claimed the state was up for grabs. States that dropped off the battleground in 2012 were also among those that lagged even further behind the national decline. Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, New Mexico, and (Pennsylvania) all fell off the map.

Battleground states should reasonably have higher turnout. The presidential campaigns and outside organizations buy up airtime to disseminate their commercials, they recruit volunteers to talk to voters, and the candidates themselves often come to town. These mobilization efforts motivate voters who perceive that their vote will matter to participate in the election.

One might take from this that the national turnout rate would increase dramatically if the Electoral College was replaced by a direct popular vote for president, something I favor. However, I caution that the turnout gains might be smaller than expected. What is not known is how much of the simulative effect of battleground status is due to increased campaign activity, and how much is due to voters believing their vote matters more in a close election. If it is primarily the former, then campaign activity -- and the amount of money spent on presidential elections -- would have to increase dramatically to reach more voters in the currently sleepy corners of the country to appreciably increase turnout when electing the president by a national popular vote.

Home Field Advantage

The state that experienced the largest participation drop-off from 2008 was Alaska, with a 9.1 percentage point decrease. The polarizing figure of Sarah Palin comes to mind as a reason why Alaskans may have been excited to vote in 2008, but were disinterested in 2012. There may be something deeper going on, however, with a national candidate fostering local interest. Paul Ryan's home state of Wisconsin was among the three states that experienced a turnout rate increase. Two states closely associated with Romney -- Massachusetts and Utah -- had the smallest declines from 2008 to 2012. Similarly, John McCain's home state of Arizona and Barack Obama's home state of Illinois increased more than the national average from 2004 to 2008. (Sorry Joe Biden, Delaware did not). While scholars find a negligible vote share gain for candidates' home states, perhaps the real effect is people who both like and dislike the favored son or daughter are energized to participate, thus cancelling each other out.

Hurricane Sandy

The depressive effect of Hurricane Sandy on participation is evident in the three hardest hit states of Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey. All were among the ten lowest decliners, with an average decline of 5.6 percentage points. It is difficult to say with certainty what would have happened if Sandy had taken a different track. If these three states' decline kept pace with the national average, nearly a half a million more people might have voted in these states. While that is a lot of people -- and I do not wish to diminish these peoples' unfortunate troubles -- they contribute only two tenths of a percentage point to the national turnout rate.

Changing Face of America

Among the most striking demographic changes in the electorate from 2008 to 2012 is that the media's exit polls indicate the share of the electorate that calls itself "White" decreased from 74% in 2008 to 72% in 2012. Census Bureau demographers forecast that by about 2050, Whites will no longer be a majority of the population (they will still be the largest racial group), primarily due to the country's increasing Latino population. It stands to reason, then, that the exit polls are the proverbial canary in the coalmine, the first to document the coming changes to the American electorate.

Only those who voted are asked to participate in an exit poll. These polls cannot truly reveal if the country's overall citizenry is changing or if the face of voters is just different from 2008. The best source of information on the demographic composition of the electorate and associated turnout rates will be the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey 2012 November Voting and Registration Supplement. This survey will be released sometime in the Spring of 2013; in the meantime information like the exit polls fill the void.

The aggregate state turnout rates also provide clues to the changing face of the electorate. A striking pattern is that states with large African-American populations experienced less turnout decline than other states. Every state (including the District of Columbia) with an African-American voting-age population greater than twenty percent fared better than the national average decline, with the exception of Georgia. (A simple correlation between state turnout rates and African-American voting-age population from the 2010 census is .33, and this does not control for the other factors already mentioned.)

Although the exit polls report the percentage of the electorate that is African-American remained steady at 13% from 2008 to 2012, some rounding error may be present, whereby the 2008 African-American percentage was rounded up to 13% and 2012 rounded down. As for Latino populations, the correlation is negative (-.20), meaning that larger state Latino populations are associated with larger turnout rate declines. Hispanics may still compose a larger segment of these states' electorates than 2008, but they are likely not contributing as much as African-Americans to the changing demographic composition of the 2012 electorate. Unfortunately, Asian-American populations are too small to draw any meaningful aggregate patterns from.

I suspect that at least part of the story of the changing face of the 2012 electorate is that Whites turned out at lower rates than 2008. The Current Population Survey will ultimately provide confirmatory evidence. Before Democrats become too giddy at the small change in the demographic composition of the 2012 electorate, which is undoubtedly slowly occurring, it is further instructive to remember that minorities' turnout rates drop-off to a higher degree in midterm elections. According to the Census Bureau, White turnout rates decreased 21 percentage points from 2008 to 2010, while African-Americans decreased 25 percentage points and Latinos decreased 23 percentage points. In the short term, the drop-off of minorities -- and young people, too -- in midterm elections poses a challenge to Democrats who wish to control congressional majorities and to win the many state offices that are more frequently elected on the midterm calendar.

Conclusion

Turnout declined in the 2012 presidential election from 2008. Only a small portion of this decline can be attributed to Hurricane Sandy, which depressed turnout in the Northeast. Perhaps the decline is not surprising since the 2008 turnout rate was the highest since 1964, or nearly half a century. The 2012 turnout rate is still higher than the entire 1972 to 2000 period. While turnout declined for Barack Obama's reelection, this is typical for modern reelected presidents. Since World War II, only two of six presidents who were successfully reelected did not experience a turnout decline from their first to second election.

Looking deeper at the state numbers, a handful of states bucked the national decline with an increase, and others were more resistant to the downward pressures -- I'm talking primarily about the battleground states. The 2012 election thus serves as yet another reminder that Americans living in battleground states experience a different quality of democracy than those elsewhere. While America's changing face leaves an impression on the state level turnout rates, an outstanding question for Democrats in the 2014 election and beyond is whether minorities -- particularly African-Americans -- will continue to be as highly engaged as they have been in the last two presidential elections.

Correction: To my utter embarrassment, I previously included John F. Kennedy among those presidents who had been reelected.

Learn more about American elections in my forthcoming book from Oxford University Press, The Art of Voting. In the meantime, the numbers and other election resources can be found at here.