I've begun rereading comic books, including titles I collected as a kid and newly discovered works. During my days as a tween and early teen, I had no idea that it was a genre frowned upon by sections of the literary elite, a form of reading seen as juvenile and of little intrinsic worth. Though this viewpoint has shifted considerably amongst the general public, with the advent of award-winning graphic novels and comic adventures becoming film blockbusters, the genre still has an outsider's status due to its history.

I also had no idea as a kid that there was continual debate going on around the shaping of brown communities and the role of women, with there being significant pushback over the concept of non-traditional or female-headed households.

My childhood has been shaped by the presence of women, as I was raised by a single mother and her own mother, both of whom immigrated to the Northeast Bronx from Panama. My other caretakers were my aunt, who I always call tía, and her three daughters. We all lived not particularly far away from each other, with my primary regular male contact being my aunt's husband, who was also my padrino.

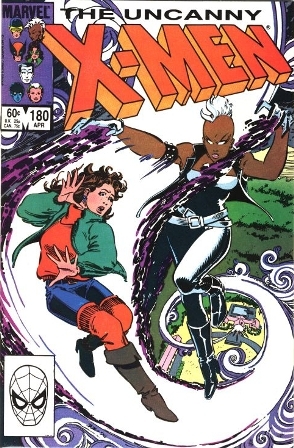

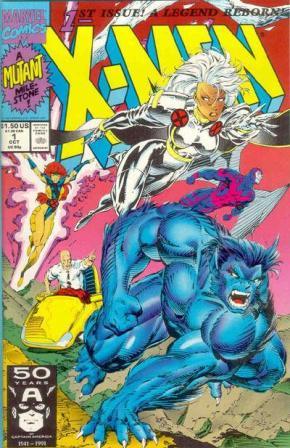

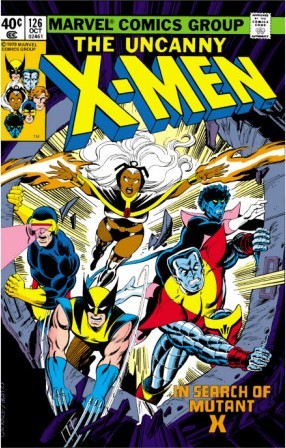

The various guises of Storm. Cover of Uncanny X-Men #126. Art by Dave Cockrum and Terry Austin.

My mother, like padrino, often worked nights, and was a generally boisterous, oft-times rancorous presence who sang "Open the dooooor, Richard" when she was picking me up from grandma's apartment and bellowing "Vamonos!" when it was time for us to go. Meanwhile, my stoic-faced and wickedly sharp grandma looked after me, cooked, gave reprimands and reminders and saw no problem with me watching nighttime TV as long as I did my work. For both of these women, there was a lot I was yet to discover.

During this time I also found solace in comics, not fitting in with the boys of the block (which grandma thought was just as well) and being a voracious reader. Like many, many others, one of the titles I took to as a kid was The Uncanny X-Men and its family of related titles helmed by writer Chris Claremont. As she did to legions of readers, an X-man that stood out was group leader Ororo Monroe, aka Storm.

Ororo possessed the ability to control weather and meteorological patterns, making her one of the most powerful beings on earth. Born in Harlem and moving to Cairo as a child with her parents, Storm was orphaned and eventually made her way to the Serengeti Plain, her ancestral home. Once her powers emerged, and taking into account her unique appearance -- brown skin, silver hair, almond-shaped eyes -- she was worshipped by the local tribes as a goddess and called "Beautiful Windrider."

(It is interesting to note that Storm found herself in a cultural context where she would be honored and venerated. Another mutant later introduced in the Marvel Comics world, Alison Blaire, the Dazzler, was also a renowned beauty who could sing, dance and transmute sound into light. She tried to make it in a cultural context known as Hollywood and the music business, where she was exploited, drugged and abused.)

I often found myself glued to the group's adventures as seen through the eyes of their African leader. And I suspect that, because of my family dynamics and growing up in a not-so-upper-crust New York City, I didn't find it at all odd or of note that a no-nonsense, electric brown woman would be leading an ethnically and mutagenically diverse team.

Rereading parts of the X-Men series as an adult, I take note that there are instances where Storm questioned her leadership, yet I also took note about how much freedom she had as a character to explore what her heart dictated. Ororo with long flowing hair embraced peace and the green. Ororo saw gentle and burly Russian immigrant Peter Rasputin as her brother. Ororo caused a Canadian hero to flee in terror after he mistakenly thought he could match her. Ororo became a surrogate mother to a brilliant adolescent, Kitty Pryde. Ororo had romance with a Caucasian warlord. Ororo explored her inner violence and edge. Ororo became punk and cut her hair into a mohawk. Ororo moved away from surrogate motherhood. Ororo lost her powers. Ororo had romance with a Native-American inventor. Ororo left the team. Ororo came back and lead the team again. Ororo regained her powers. And there was so much more.

Through all of these permutations and plot points, Ororo's womanhood and skin color -- and for that matter mutanthood -- was not a hindrance to her human experiences.

In this case, an outsider's genre offered a less rigid notion of womanhood than that often discussed in popular media and casual circles. A comic character metaphorically reflected the possibilities of the women I grew up with, the women I've befriended as an adult and the women whom I've worked with or for in the publishing world.

I contrast my comic reading with the more "informed" reading and dialogues I've experienced as an adult, routinely coming across the idea that women, and especially brown women, should apologize or step back for being free. Or that they should make room for a demeaning hyper-masculinity. I've sometimes seen how these notions have caused people to stick themselves in ghettos, both literal and metaphysical, have robbed girls of their foresight and strength and robbed boys of the comfort found in being vulnerable and passive.

To be clear, the male-dominated comic-book genre has had a fair share of misplaced notions around gender and ethnicity. And at the end of the day, I don't think the format is something that works for everyone, regardless of age and upbringing. But I think that the case of Storm as originally conceived brings up interesting ideas as to how we can get in touch. She reminds us that we should never use something that is diabolically contrived to dictate what our experiences can be. That there is worth in the most sidelined of genres and truth in the unconventional. That many of these stories can serve as modern myths to help us figure out who we are.