Political commentators and onlookers often speculate about the possible effects that late-breaking news might have on a campaign. Will the president's handling of the hurricane affect the race? Will the October jobs report shake things up? The fact is, there is little chance of moving the needle much at this late stage of the campaign. Most voters have known for quite some time which candidate they intend to support in November (and of course, many have already voted), and new facts are often processed by voters in a manner that will cause the least amount of disruption to their well-solidified preferences (a phenomenon known as motivated reasoning).

A good example of how voters process new information during a campaign comes from a UMass Poll we conducted in early October. In this poll of registered voters in Massachusetts, we asked respondents whether they thought that the unemployment rate had increased or decreased during the past year. At approximately the mid-point of our field period for the survey, the September jobs report was released, with news that the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.8 percent. The drop in unemployment was significant and received much attention in the news media that day and during the rest of our field period. Not only was the unemployment rate 1.2 points lower than it had been 12 months earlier, it was at its lowest point since Obama had taken office.

Given the significant news coverage of the favorable jobs report, we expected respondents to more accurately answer the question about whether the unemployment rate had dropped during the past year. We did see some "learning" taking place. Among respondents answering our survey before the jobs report, 25 percent said that the unemployment had decreased over the past year compared to 44 percent who said it had increased (25 percent said it had stayed the same). After the report was released, 38 percent said that the unemployment had decreased during the previous year, while 33 percent said it had increased. Those interviewed after the jobs report were clearly more likely to get the answer to this question right.

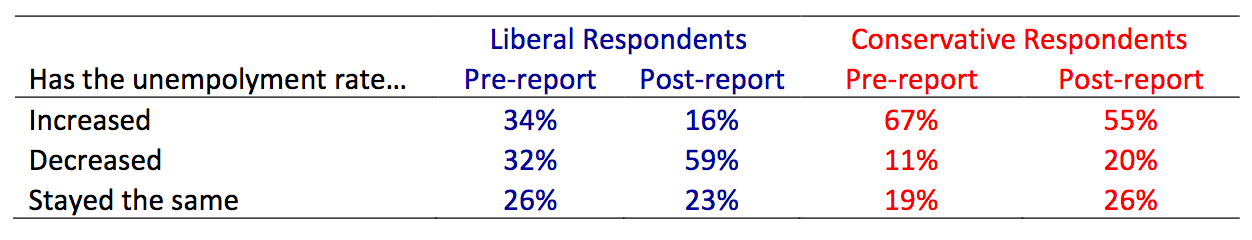

But as we drilled down into the data, what we discovered is that while some respondents were more likely to get the unemployment question correct after the jobs report, not all groups did better on the question later in the field period. As the chart below shows, respondents who identified as liberals were most likely to respond to the jobs report and give more accurate answers to the unemployment question, while respondents identifying as conservatives barely changed their answers at all. Liberals answering the survey after the jobs report were 27 percentage points more likely to answer that the unemployment rate had decreased during the past year while conservatives were only 9 points more likely to answer the question correctly.

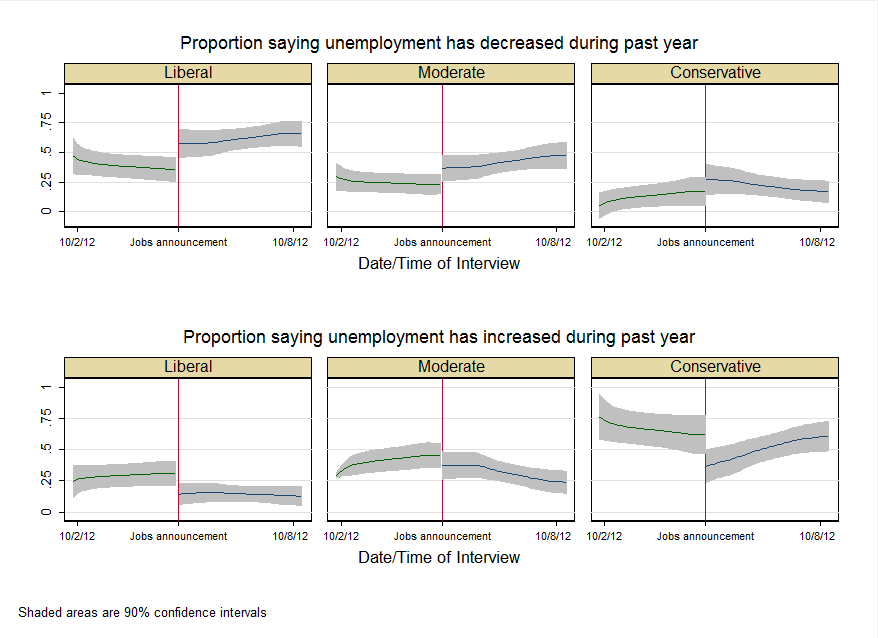

What is even more striking is watching how each group of respondents answered this question depending on the date and time at which they took the survey. The chart below plots this pattern, dividing the data by the moment that the jobs report was released. Note that immediately after the jobs announcement liberals are much more likely to say that the unemployment rate had decreased over the past year and much less likely to say that it had increased. A very different pattern presents itself for conservatives. Conservatives initially react to the news as well; respondents answering the survey immediately after the jobs report were more likely to say that the unemployment rate had decreased in the past year and less likely to say that it had increased. However, as more time passed after the jobs announcement, conservative responses began to regress back to where they had been prior to the announcement. Indeed, within a day or two of the jobs report, conservatives were back to answering the unemployment question about as they had prior to the report.

Of course, one can only speculate as to why we see these distinct patterns from liberals and conservatives. However, it is important to recall that Republicans immediately started questioning the veracity of the jobs numbers, with some suggesting that the Obama administration had "cooked the books" for political gain. Our data suggest that as this meme spread, some conservatives in our survey may have started to discount the jobs report, thereby leading them to answer the question much as they would have before the announcement. In short, conservative elites provided conservative voters with an argument that allowed those conservative voters to bring the information from the jobs report into line with their pre-existing political preferences. The end result was that liberals updated their beliefs about the unemployment rate based on the jobs report while conservatives ultimately did not.

Overall, these results illustrate the limited effect that new information will have at this late stage of a presidential election campaign. Most voters have long ago decided who they plan to support and new information tends to be processed through this lens. When the jobs report is released on Friday, it will likely be embraced by one candidate's supporters and dismissed by the other side. What is unlikely is that it will move the needle much at all in terms of the presidential race. Such is the nature of information processing at the end of a long, polarized political campaign.