An unusual gathering of diverse cultures occurred recently in an exceedingly remote yet beautiful area of the Great Plains. On a clear, sunny day in early March, members of Montana's White Clay (Gros Ventre) and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Indian tribes, ranchers, conservationists, scientists from World Wildlife Fund, American Prairie Reserve (APR) employees and volunteers assembled for a celebration of youth. The youth in this case were 70 rather bewildered and very nervous bison calves that only a month earlier had arrived in Montana from Alberta's Elk Island National Park. After thirty days of required quarantine, they were to be released into a 14,000-acre enclosure and hopefully accepted by American Prairie Reserve's existing bison population of 125 animals. The welcoming party -- somber bulls weighing 2,000 pounds and standing six feet at the shoulder -- glowered at the transfixed youngsters moments before the gates were opened by the youngest of the tribal members.

An unusual gathering of diverse cultures occurred recently in an exceedingly remote yet beautiful area of the Great Plains. On a clear, sunny day in early March, members of Montana's White Clay (Gros Ventre) and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Indian tribes, ranchers, conservationists, scientists from World Wildlife Fund, American Prairie Reserve (APR) employees and volunteers assembled for a celebration of youth. The youth in this case were 70 rather bewildered and very nervous bison calves that only a month earlier had arrived in Montana from Alberta's Elk Island National Park. After thirty days of required quarantine, they were to be released into a 14,000-acre enclosure and hopefully accepted by American Prairie Reserve's existing bison population of 125 animals. The welcoming party -- somber bulls weighing 2,000 pounds and standing six feet at the shoulder -- glowered at the transfixed youngsters moments before the gates were opened by the youngest of the tribal members.

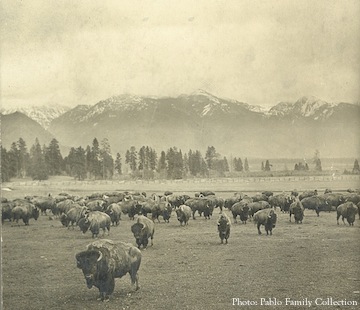

The calves' improbable journey to this expansive landscape started 130 years ago. Legend has it that in 1873, a Pend d'Oreille American Indian named Samuel Walking Coyote brought six bison to northwest Montana after a hunting trip on the east side of the state. He soon sold his fledgling herd to his neighbor Michel Pablo and business partner Charles Allard, who died shortly after the deal was struck. A decade later, through further supplementing from other herds, Pablo's band numbered 600 and was again sold -- this time to the Canadian government.

Over time they became one of the most, if not the most, important conservation herd in North America, as they carry no diseases and -- unlike more than 95 percent of bison in the United States -- carry no cattle genes in their DNA. These 70 calves about to be released on the APR are direct descendants of Samuel Walking Coyote's and Michel Pablo's herd.

Marcia Pablo, a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes, attended the event with her family. She explained that in her tribe and many others, there is a tradition of considering the impact one's decision would have on people seven generations into the future. Standing next to her as she addressed the group were two of her grandchildren -- descendants, exactly seven generations removed, from Michel Pablo. She poignantly said:

We are honored to be part of this celebration, to see descendants from the Pablo herd coming back to Montana, coming home... In Native American beliefs, the circle is a sacred symbol. Today we see the circle being completed, as the descendants from the Pablo herd are back in the United States once more, thanks to American Prairie Reserve.

George Horse Capture Jr. of the White Clay (Gros Ventre) tribe also addressed the crowd. He noted that he is very pleased to see the changes that have occurred on American Prairie Reserve over the past 10 years. There are fewer buildings, far less barbwire fences -- the land is slowly being opened up and looking more the way it used to be. Tears came to his eyes, and to many of those listening, when he said that seeing these young bison being released onto this landscape was, to him, a sign that, slowly, things are being set right again.

After the speeches and lunch, the crowd moved out to the corral, where the uneasy calves awaited their freedom. As Marcia Pablo and her grandchildren ceremoniously swung open the steel gates, an initial stream of 50 or so calves exploded out of the corral. Like Fourth of July bottle rockets, they careened towards the waiting herd of adults some 300 yards away. Twenty or so edgy youngsters remained pressed against the back rails of the corral.

Robe Walker, also from the White Clay tribe said, "Shall we sing them out?" His booming voice projected a beautiful White Clay song -- translated as, 'It is Good to Be Young' -- up into the bright blue sky and cumulus clouds. Another burst of calves charged out of the gate and made the crossing in what seemed like seconds. The bison spent the rest of the afternoon quietly integrating the newcomers into the group's matriarchal culture. The human guests -- ranchers, American Indians and scientists -- continued the feast, sipped beer, and talked of the exciting trajectory of the American Prairie Reserve project.

Robe Walker, also from the White Clay tribe said, "Shall we sing them out?" His booming voice projected a beautiful White Clay song -- translated as, 'It is Good to Be Young' -- up into the bright blue sky and cumulus clouds. Another burst of calves charged out of the gate and made the crossing in what seemed like seconds. The bison spent the rest of the afternoon quietly integrating the newcomers into the group's matriarchal culture. The human guests -- ranchers, American Indians and scientists -- continued the feast, sipped beer, and talked of the exciting trajectory of the American Prairie Reserve project.

Within a few days, we attendees were all back in our own worlds of ranches, Montana Indian reservations, a wildlife reserve, Chicago and towns on the California coast. Separately, we live very different lives, but together, we are passionately connected by a common desire to see nature restored at a grand scale, and our awe-inspiring, prairie-based wildness preserved for future generations.

This event was covered by journalist Natasha Loder in the 19 March 2012 issue of The Economist. To learn more about American Prairie Reserve, visit americanprairie.org and facebook.com/americanprairie.