This blog is part of an ongoing series made possible through the State of the Rockies Project.

Alex sets up a self-timed camera with exaggerated care. Pointing the lens across the alpine valley in British Columbia where we're camped, he takes several practice shots of two waterfalls draining from a small glacier. He adjusts the camera's height and angle, shoots, adjusts again. It's late morning, and the rest of us are drifting lazily about camp as Alex's movements draw our attention. There are four of us here to take his picture, and his unnecessary use of the self-timer clues us in to an impending stunt.

Alex is finally satisfied. He hits the button, runs in front of the camera, slaps on a goofy grin, and gestures to the water and ice. We look on questioningly. "It's for my future kids," he explains, "so I can show them what a glacier looked like."

We all laugh, wishing he was joking.

Alex's self-timed picture in southern British Columbia.

A few hours earlier, I had sat up in my sleeping bag and looked upon the same scene as the last stars were fading with dawn. The summer night north of Montana was over in five or six short hours, but the darkness had still cooled off this valley enough to slow the two waterfalls to a trickle as the glacier paused its labored melting. By the time I finally left my sleeping bag, however, the waterfalls had regained speed once again, falling several hundred feet and being blown to mist before hitting the valley floor.

Our crew is spending a week hiking and boating in and around Glacier National Park to document large scale land conservation efforts in the region as well as the effects of climate change. The latter isn't hard to find. On this particular morning we're a few miles north of the U.S. border in Canada and can see the evidence of melting glaciers in several directions. Alex, though he's the youngest member of our crew, is perhaps the most distressed by the last several days of taking repeat glacial photography and interviewing environmental groups. After wrapping up his sophomore year at Colorado College, Alex was hired by the State of the Rockies Project to help us spend the summer filming endangered landscapes in the Rocky Mountains. I think it's safe to say that the warming globe weighs more heavily on his mind than most 20-year-olds. Back in school, Alex is helping lead the student-run fossil fuel divestment campaign along with climate allies at 350.org. Modeled on the international movement to divest from companies who supported South African apartheid, the campaign hopes to pressure fossil fuel corporations into leaving enough of their "product" underground to avert the worst effects of climate chaos. The college's board of trustees has yet to agree that risking a percentage of their endowment to take a small stand against the global crisis is prudent, so Alex has plenty of work ahead of him.

The college's reluctance to change is not unusual, of course, even for those of us who believe that carbon dioxide may be the most pressing threat humanity has ever faced. Most of us defer responsibility, point fingers, take small, symbolic actions, and hope for the best. Meanwhile, the temperatures keep climbing.

It's easy enough to ignore global warming when we're in front of a computer screen or at the grocery store. It's more difficult when we stand in front of a melting glacier.

And the little glacier in Alex's picture is in its death throes. Between our camp and the other side of the valley there is a several thousand foot drop. We're only a mile from the top of the drainage, and it's clear that this spectacular valley was carved not by liquid streams but by the powerful grind of flowing ice. Now, the last remnants of that ice are fast in retreat. Glacier National Park, just a few miles south of our camp on the other side of the border, makes the point for the whole region (and the whole world for that matter); of the 150 large glaciers counted in current park boundaries in 1850, only 25 remain. And they're not sticking around for long. Alex's joke is not a joke. All the glaciers in the park could be gone in the next 6 years, as soon as 2020 -- and it's unlikely any of Alex's future children will be around to see them.

photo by David Spiegel

At the mouth of the steep-walled valley where we're camped lies a high mound of debris where the once-enormous glacier ended. It's been melting since the last ice age ended around 12,000 years ago. The melt began long before the invention of the combustion engine when the global human population was around 5 million (less than the size of New York City today) and the idea of the species altering the global climate would have been inconceivable. Climates have always changed. Glaciers form and melt. Mountains are carved and carried to sea. This much is clear from spending even a few hours in this landscape. So why is this current spike in warming so serious?

The answers are many -- as pressing as they are familiar -- from threats to public health, rising seas, loss of arable farmlands, conflicts over resources and so on. But another, often understated, answer is visible from our camp: habitat connectivity. Just beyond the end of the former glacier, there lies a landscape of rolling hills and thick forests, broken only by a line cut through the trees along the border with the U.S.. This is known as the Flathead Valley, which a coalition of local environmental groups calls the "last unprotected piece of Glacier/Waterton International Peace Park." Being at a lower elevation than the surrounding area, it boasts much higher biodiversity than the protected lands in the park. The Flathead is one of those rare, precious places where you could wander for days and only have contrails from jets to indicate you were still in the 21st century. The valley is home to the densest grizzly bear population in inland North America, its rivers carry the cleanest water in the region, and it is the southernmost place on the continent to still host the full regime of native predators: wolverine, grey wolves, mountain lion, lynx, and the grizzlies.

The ancestors of these creatures survived and evolved through endless cycles of warming and cooling, but now their fate is uncertain. Formerly, when ice crept down from the north, the ecosystems shifted south or down to lower, warmer elevations. When the climate changed relatively slowly and habitats remained connected, whole hosts of species were able to migrate without suffering any major extinctions. The problem today has two main components. First, the globe is currently warming at a much faster rate than past warming cycles, making adaptation more difficult. Second, the corridors that these species once travelled along are fragmented by backcountry cabins, highways, ranches, towns, mines, logging operations, reservoirs, interstates, cities, fences -- and the list goes on. The once unimpeded ecosystem shifts down the spine of the Rockies are now blocked in a thousand complicated ways by human activity. Some conservation biologists have likened the protected cores of national parks and wilderness areas to islands separated by inhospitable seas of degraded habitat, which makes undeveloped, mid-elevation habitats like the Flathead Valley crucial to the long term survival of wildlife and plant populations. These areas are not only important because of the species they support right now, but also because of the safe corridor they will provide for migrating species in the future.

Mountain goat in Glacier National Park. Photo by David Spiegel

The crucial difference between now and the last ice age is that we're going into this cycle of global warming in the midst of the sixth greatest extinction since life appeared on the planet, and habitat fragmentation is a leading cause of the crisis. Nearly every large-scale habitat on the globe has been compromised in some way, and the fewer places ecosystems can shift to as weather warms, the worse they will likely fare. Thankfully, there is an ever growing number of dedicated scientists and conservationists across the planet working to protect landscapes with habitat connectivity in mind. In the Northern Rockies, the Flathead Valley is just one key place in an ambitious conservation vision called Yellowstone to Yukon which has brought conservation groups on both sides of the border together around a common goal: ensuring landscapes will remain unified into an uncertain future.

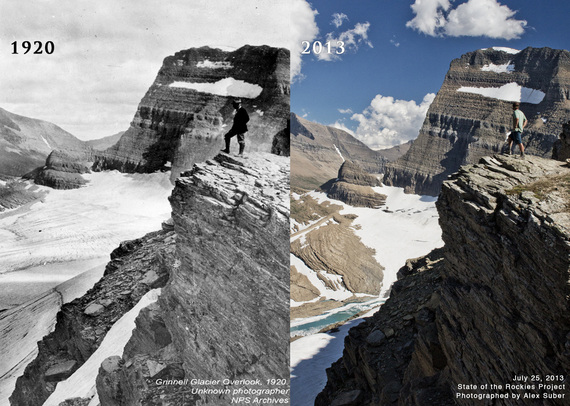

A few days after the backcountry morning in B.C., Alex is setting up the camera and tripod again before a different glacier. This time, we're in Glacier National Park and the we're trying to find the exact spot a photo of the Grinnell Glacier was taken from in 1920. Even holding up the small, grainy picture printed on computer paper to the mountain before us reveals just how much ice has disappeared in the last century. Later, when we see the photos side by side, a thousand nauseating arguments about the reality of climate change are quieted in a single glance. The planet is warming; the question is how much we will be able to mitigate the consequences of this fact. Fighting to keep fossil fuels undrilled and working for large landscape conservation seem like good places to start.

To learn more about the effort to protect the Flathead Valley, click here.

Our crew's repeat photo of Grinnell Glacier. Photo by Alex Suber