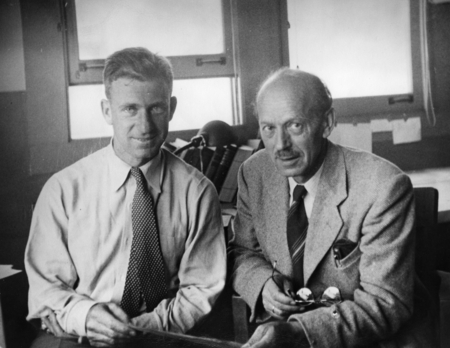

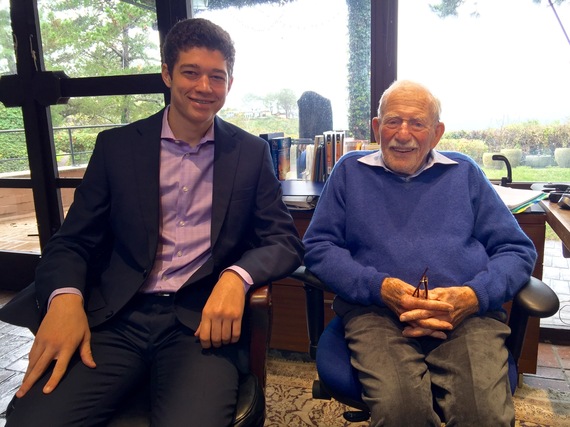

January 31, 2016. Max Guinn and Walter Munk, at Munk's home in La Jolla, California. Credit: S. Guinn

Ask my generation--I am 15--to identify its heroes, and you will likely be given a roster of NBA names. Few, if any, have heard of Walter Munk, the world's greatest living oceanographer. Called "The Einstein of the Oceans" by the New York Times, Munk's scientific contributions are almost unbelievable. Following Munk's accomplishments is a Forrest Gump journey through history.

As far as great inventors go, Munk ranks with Thomas Edison. He is recognized for groundbreaking discoveries in wave propagation, ocean drilling, tides, currents, worldwide ocean circulation, and even our understanding of why the moon stopped rotating. His work serves as the basis for deep sea oil drilling and scientific ocean exploration.

However, the legendary 98-year-old Munk may be best known for a scientific discovery he made when he was only 24, which arguably led to Allied forces winning World War II.

In 1942, Munk took a job in the Pentagon. At the time, the Germans were overrunning Europe. American troops, about to embark on their first wave of amphibious landings in Northwest Africa, were practicing beach landings in South Carolina. Watching, Munk learned when the bow of the landing craft dropped, to allow soldiers to storm the beach, waves higher than five feet broke into the craft, injuring them. Researching average wave heights in Northwest Africa, Munk found they exceeded six feet. Unless wave heights could be predicted, soldiers were likely to drown.

Amphibious landing craft, http://www.strijdbewijs.nl/landing/landeng2.htm

Munk proposed using science to determine wave predictions to time landings to wave heights less than five feet. Too junior to be taken seriously, Munk was ignored. Munk recruited his mentor Harald Sverdrup, the past director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (Scripps), to help. Given Sverdrup's fame, the Navy conceded the two should try. Together, they developed the Sverdrup/Munk Theory of Wave Prediction, which soon allowed for the safe landing of troops in North Africa. They had done what no one had done before, used science to predict surf conditions.

As part of the war effort, the two established a school for wave prediction at Scripps, and over the next two years, they taught wave prediction to 100 graduates. In June of 1944, the graduates played a critical role in the D-Day landings in Normandy. The landings were originally scheduled for a stormy day, with high waves. Considering the wave predictions, Eisenhower postponed the landings to coincide with a 12 hour period of moderate waves. The Germans believed the sea would remain too rough for an invasion for another few weeks and, as a result, German General Rommel went home for a birthday party for his wife, taking the defenses way down. Equipped with excellent surf forecasting, Allied troops began landing at 3 in the morning on June 6. It was the beginning of the end of World War II.

June 6, 1944. Allied troops landing on Omaha Beach, Normandy, France. http://www.lexpress.fr/diaporama/diapo-photo/actualite/societe/6-juin-1944-le-debarquement-en-images_1549231.html

Following World War II, during the height of nuclear testing, the United States planned to test a hydrogen bomb in the Marshall Islands. Worried the H-Bomb would trigger a tsunami, flooding the nearby islands and potentially drowning thousands, Munk and a team from Scripps developed an automated system to warn people to abandon low-lying areas as needed.

1952 hydrogen bomb testing, Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands. http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-bikini-atoll.htm.

Munk recalls, "I should not forget the experience of being in a tiny little raft, in the middle of a big ocean, and probably I think the closest person to the H-Bomb -- seeing it go off....I was aboard the Scripps' ship Horizon, and we had an Air Force officer along whose job was to monitor radioactivity, just for that reason, and he had his Geiger counters. I was up on deck and he came up and shoved them in our belly and it went -- it showed a lot of radioactivity.... He said, oh my god, we've hit radioactive rain. And so we all had to go down and throw our clothes overboard." No tsunami resulted but the warning system was ready. The principles are still in use.

Munk was also the first to determine why only one side of the moon faces the earth, attributing the moon's slowing rotation and eventual stop to tidal friction.

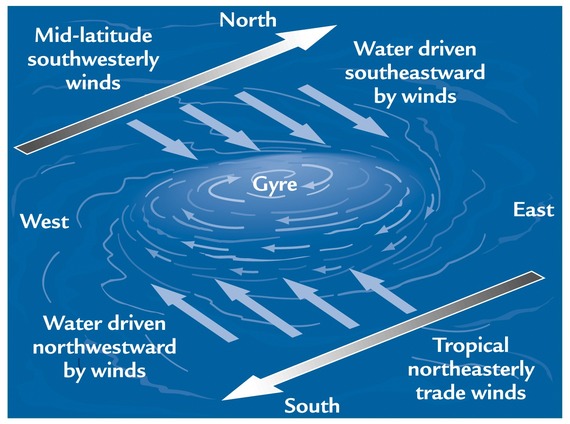

He pioneered research on wind-driven ocean gyres, finding that stress at the ocean's surface caused from wind blowing from west to east, and trade winds blowing from east to west, created regions of enormous torque. These areas or gyres cause the principal circulation in all the oceans of the world.

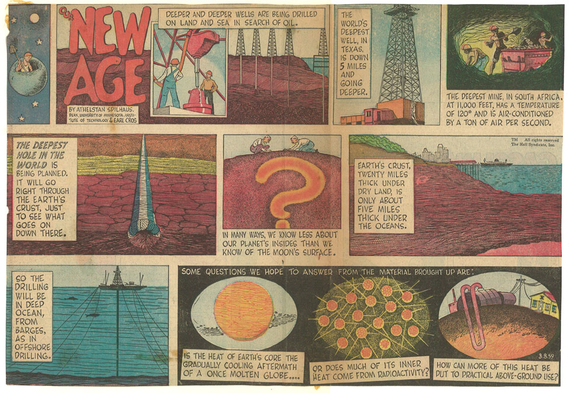

Before Munk, deep sea drilling was thought impossible. There was no known method of keeping a drilling ship stationary, as there was no form of stable measurement or GPS. Munk and his team devised a system using sound for triangulation. The vessel sent and received sound impulses from three transponders on the ocean floor. By measuring the time it took for the impulses to travel between them, they were able to calculate the ship's exact location. "That had never been done," Munk told me, "and that was really, tremendously important because it became the basis of deep sea drilling for oil." This work also served as the foundation for drilling in the deep sea floor for scientific reasons, becoming a major source of geologic research for the last fifty years.

Tracking ocean swells 15,000 miles, across oceans, Munk proved waves that were generated in the South Indian Ocean traveled between New Zealand and Antarctica into the South Pacific and North Pacific Oceans.

At the forefront of tidal research, Munk built and designed the first deep ocean censors to measure tides. Before this, tides had only been measured in shallow areas such as harbors. For ten years, he measured tidal induced changes in seafloor pressure all over the world. This provided essential tidal wave data for the deep seas.

In 1975, using water temperature and sound, Munk and Carl Wunsch pioneered the development of acoustic tomography of the ocean, which is critical to understanding the ocean's climate. He discovered there is ocean weather, just as there is atmospheric weather. Previously it was thought the ocean was responding to seasonal changes such as winter to summer but otherwise there was no difference. This knowledge was a game-changer, forever changing mankind's understanding of climate change, and the ability to monitor it, above and below the surface.

When I asked if Munk believed climate change is man-made, his response was immediate. "There's no question, in my mind, that the release of, the increase of CO2 in the atmosphere, which is certainly the result of human activity, is responsible for climate change."

The advice Munk has for my generation: "I think our students have become too sensitive about tackling problems...and finding out their hypotheses are wrong. Well, I think that some of the most important discoveries are when things did not work." He may have reflected on our 83-year age difference when he smiled and told me, "Do things you enjoy and don't be afraid that some things you try don't work."

Some 75 years after beginning his career at Scripps, Munk has no plans to retire. Before he reaches 100, he hopes to understand an experiment he did fifty years ago, which led to unexpected results. He found that the short wave slopes associated with ocean surface roughness are, curiously, almost as big across as up as down. He wants to understand why. No doubt he will.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Follow Max Guinn on Twitter and Facebook. Like Kids Eco Club to stay connected.