"I was five years old when my American father left me. I don't know why he did this. I keep looking for him everyday and hope that I'll see him again."

Haunting words that kept repeating in my head on a one humid rainy night in Angeles City, Philippines. I was on my way home from a friend's gathering with a box of biscuits locally called otap, and I shared a ride with a young man in his early twenties whose name is Eric. I noticed he had unusual features, a fusion of Asian and Caucasian facial attributes, which tweaked my curiosity. I started probing into his background and with his head shamefully bowed down, he replied, "My mother is a Filipina, and my father was an American." That started our conversation, and he said that he was abandoned as a child and cannot remember his father although he often wondered about him - where he lives, if he is still alive, or if he still remembers him.

Eric grew up with his impoverished mother and has been discriminated mercilessly for being abandoned. With no access to education, he did not have a chance to change his fate. Left with nothing to survive, Eric used his unique facial attributes to make a living - he turned to prostitution. He said, "This is the only thing I know to do. I have no choice. If I had a choice, I wouldn't be doing this." And with a tremor in his voice, he continued, "I still hope my life will change."

The jeepney (a local bus) we were riding stopped and it was time for me to get off. I had an urge to learn more about the story of the sad, young man but with nothing left to say, I gave him the biscuits and his hands clung to them as if they were his lifeline, he thanked me quietly. His sad eyes followed me as I got off the jeepney and he continued his journey.

I flew back to New York City with an unsettled feeling. Eric's eyes haunted me and I could hear his voice saying "I hope my life will change" over and over again. At that moment, it hit me; I felt an obligation to make a difference in this young man's life and thousands more abandoned sons and daughters of U.S. military men out there. There are apparently more "Erics" living in the Philippines -- young people who were left behind in a third world country by their first world American fathers.

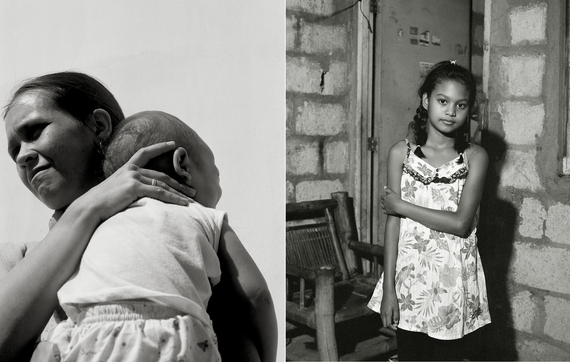

They are called Amerasians, a term coined by the American author and activist Pearl S. Buck to describe children of American servicemen and Asian mothers. The term was eventually formalized by the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service. Many Amerasians in the Philippines live in squalor, suffer a life full of mockery, racism, self-identity issues, and are stigmatized in a highly conservative Catholic country. The number of Amerasians is thought to be between 200,000 and 250,000.

Countless Amerasians have longed for help since their abandonment, desperately seeking societal acceptance in the Philippines and legal recognition by the U.S. government. Yet, to this day, both governments have largely ignored their pleas for help. Even after the end of American colonial rule, the Philippines hosted two of the United States' largest overseas military installations for more than 50 years. The closure of these bases in 1992 left thousands of fatherless Amerasians.

"I look American and I get called half-dollar, bye-bye daddy," cries Katherine. Growing up in the Philippines was not easy for Katherine because of social ostracism. "I don't feel welcome," she continues. Katherine finally found her father in the U.S. but due to an antiquated law, she is not approved to enter the United States. "I feel unwanted in my motherland yet not welcomed in my father's land," she concludes with tears in her eyes.

In 1982, the U.S. passed Public Law 97-359 known as the "Amerasian Act," a law which was enacted by the 97th Congress that permitted Amerasian children born in Laos, Kampuchea, Vietnam, Thailand, and South Korea to enter the United States through preferential immigration treatment. Though the Philippines and Japan were originally included in the Act's list of countries, they were deleted at the last minute. It remains a mystery why Congress excluded the Philippines from the Act.

Eric and Katherine's story is a multitude of similar scenarios shared by the hundreds of Amerasians I photographed. I am compelled to put a face to the issue and shine a light in their unfortunate situation. Photography is a powerful tool, and often times words are not enough to express hope. I hope that both governments will see these faces and that the photographs will humanize the consequences of their abandonment.

Both allies recently agreed on reinstalling U.S. military bases in the archipelago under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement - a deal between the United States and the Philippines in order to strengthen the U.S.-Philippines alliance. The agreement is due to the rising tension and China's territorial conflict in the South China Sea. With this consent, I ask a very important question:

"Should another child be left behind?"

All Photographs Copyright to Enrico Dungca, 2013-2016

Enrico Dungca is a photographer based in New York City.