A quarter of a century ago, the phenomenal Argentinian soccer player Diego Maradona scored a goal with his hand during a quarterfinal match against England at the 1986 FIFA World Cup in Mexico. The referee didn't see the hand-play, allowed the goal and Argentina went on to win the Cup. "It was a hand of God," Maradona said later. Garry Kasparov used the same quote after an incident during his game against Judit Polagr in Linares, Spain, in 1994. The world champion finished a knight move, changed his mind, grabbed the knight again and moved it to a different place. Like in any sport, there are chess players who try to win at all costs, bending the rules in their favor. But there are also noble chess warriors who believe in decency and fair-play.

It was a moment of disbelief when the game between the Czech David Navara and Alexander Moiseenko of the Ukraine finished Sunday at the 2011 World Cup in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia. The official website showed the result as a draw, but the position was clear: Navara was about to deliver a checkmate in a few moves and Moiseenko had no way of escaping.

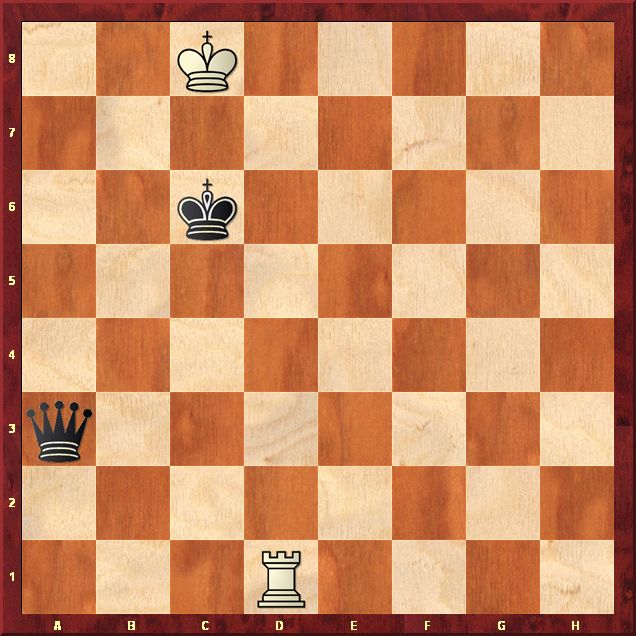

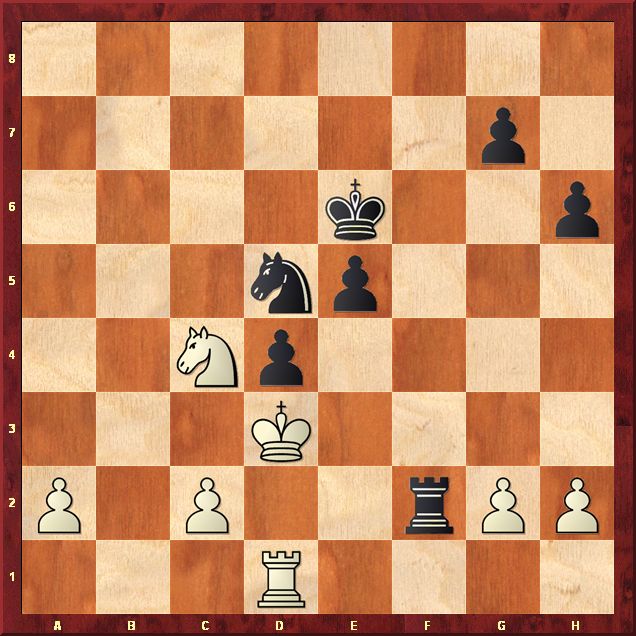

Moiseenko-Navara

World Cup 2011

Final position

Great online scramble ensued in an effort to find out what happened in Siberia. It was an important game: the loser would be eliminated from the competition, the winner would have a chance to increase his prize money and qualify for the next world championship. Navara, in fact, confirmed in an e-mail after the game that he offered his opponent a draw. The match was tied 1-1 and was headed to a tiebreaker the next day. Did Navara have a reason to be so gracious? Does it pay to be nice?

We know the answer to the second question. Navara won the tiebreaker and also eliminated his next opponent, another Ukrainian grandmaster, Yaroslav Zherebukh. The Czech was on his way to the quarterfinals.

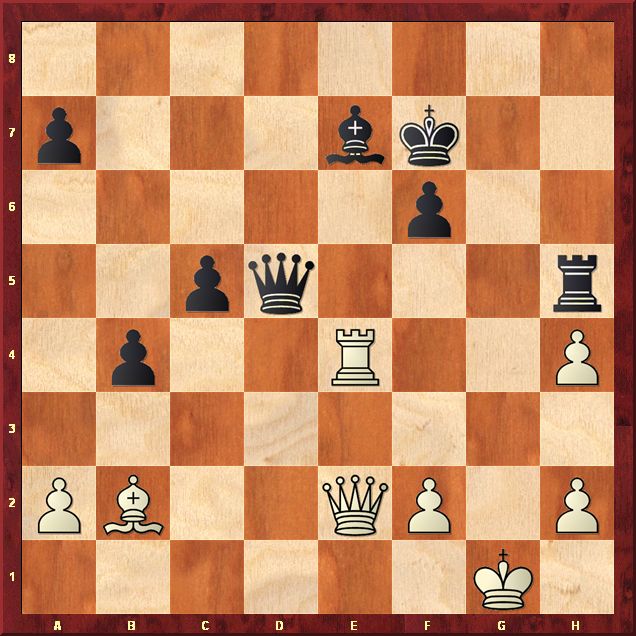

The game with Moiseenko took a dramatic twist in the following position:

Moiseenko-Navara

World Cup 2011

Navara tried to play 35...Be7-d6, but when he was reaching for the bishop he accidentally clipped his king. Moiseenko's reaction was spontaneous. "King moves," he said, trying to take advantage of his opponent's misfortune. He knew well what Navara's intention was, but the temptation to win the game outright overwhelmed him. After any king move, black loses the bishop and the game. Navara acknowledged that he touched both pieces, the king and the bishop, but he wasn't sure which piece he touched first. What to do? The arbiter arrived and Moiseenko decided not to insist on the king move. The players agreed to continue, but a certain discomfort prevailed till the very end.

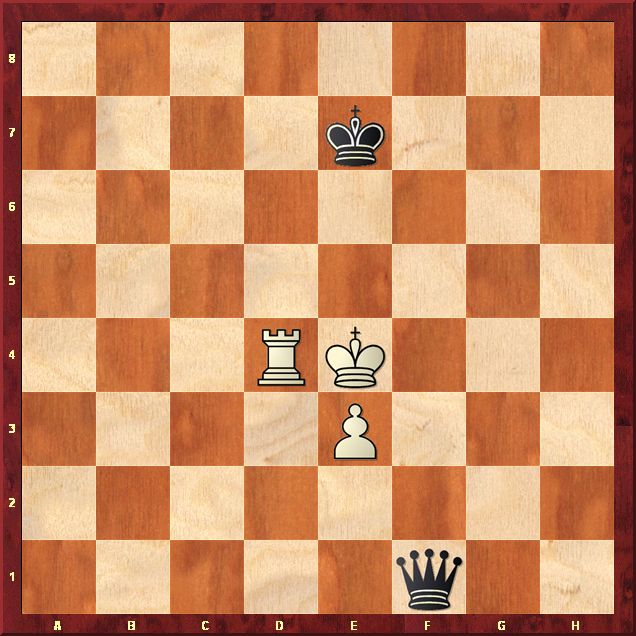

At one time they reached an endgame I was familiar with

Navara - Moiseenko

World Cup 2011

A deja vu from my duel against the Hungarian grandmaster Levente Lengyel from the tournament at the Bulgarian coastal resort of Varna in 1965. The victory in the game lifted me towards a GM norm and I became a grandmaster later that year.

Lengyel-Kavalek

Varna 1965

Black can win by running his king behind the e-pawn, somewhere around the square e2. To achieve it, black has to use the zugzwang, forcing the rook or the king out of their best defensive set-up. Any advance of the pawn weakens the defense and helps to win. This is easier said than done, but in those days games were adjourned and you could hit the endgame books and learn what to do. I found out the endgame was already analyzed by Andre Danican Philidor in the second edition of his Analyse du jeu des Échecs published in 1777. I didn't even have to make the long king's journey.

The game ended the following way:

81. Rd4 Qg2+ 82. Ke1 Qf3 83. Kd2 Qf2+ 84. Kd3 Qe1 85. Re4+ (85. Ke4

Qf1! ) 85... Kd5 86. Rd4+ Ke5 87. Re4+ Kf5 88. Rf4+ Kg5 89. Kd4 Qd2+ 90. Ke4

Qd1 91. Ke5 Qd3 92. Re4 Kg6 93. Kf4 (93. Rg4+ Kh5 94. Re4 Kg5 zugzwang) 93...Qd6+ 94. Kg4 Qd5 95. Rd4 Qg2+ 96. Kf4 Qf2+ (White must lose the -epawn since after 97. Ke4? Qf5 black mates.) White resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

You don't have the luxury of adjourning today, but you can practice it against an endgame tablebase run by a computer. The electronic programs can be intimidating. They can tell you, for example, that a mate is achievable in 46 moves. Navara knew how to win the e-pawn, but after he did it he had 50 moves to mate Moiseenko. If he could not do it, the game would be declared a draw according to the FIDE rules. The Ukrainian GM played the defense as well as he could and after Navara made a few inaccuracies, Moiseenko's chances to draw increased. As a matter of fact, he could have sent the game beyond the 50-move limit with a precise play, but that was humanly impossible.

The Czech was winning, but he could not forget what happened earlier in the game. "My opponent is a decent man and we had a misunderstanding," Navara wrote. " I don't know who was formally right." He felt the match should not have been decided by this crazy game or by a protest without sufficient evidence. He didn't want to be accused of advancing unfairly and offered a draw. They began the tiebreaker next day with a clean slate and the better player won.

Both players received the Fair Play Prize after their match specially created by the Governor of Ugra, Natalia Komarova. "I lost not just to a very strong player, but also to a noble man," Moiseenko commented. "I think David's decision to offer me a draw is unique for the chess world. No one else would do it under such circumstances."

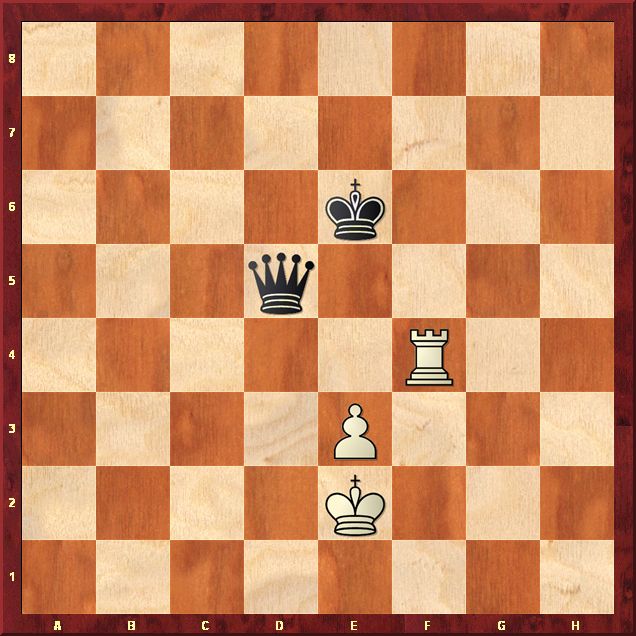

Generosity can sometimes backfire. At the end of a strong tournament held in a German spa Baden-Baden in 1925, Karel Treybal, having a clearly won position, accepted a draw offered by the American champion Frank Marshall.

Treybal - Marshall

Baden-Baden 1925

Black just played 32...Nd5, threatening to mate with 33...Nb4+ 34.Ke4 Rf4 mate. To prevent it, white has to jettison couple of pawns. Rather than resigning, Marshall resorted to his last option: he proposed a draw. The Czech lawyer was the only amateur in that event and he didn't want to interfere with the American's chance to make more prize money. He accepted Marshall's offer.

It didn't go well with a group of players, led by Ernst Grunfeld (the same one behind the Grunfeld Indian defense) and they protested against the result. Treybal was reprimanded by a jury for being so generous to Marshall. He defended himself by saying that he didn't see a clear winning way, but the jury didn't buy it. "A player of Treybal's strength should be able to play such a winning position for a win," they concluded.

The World Cup Update

The field of 128 players will dwindle to eight by Thursday. Three players already qualified for the quarterfinals on Wednesday:

The Russian champion Peter Svidler (eliminating the U.S. champion Gata Kamsky),

Teimur Radjabov of Azerbaijan (defeating Dmitry Jakovenko of Russia) and Navara.

Five players will advance from the tiebreakers on Thursday. The pairings are as follows:

Judit Polgar (Hungary) - Lenier Dominguez Perez (Cuba)

Alexander Grischuk (Russia) - Vladimir Potkin (Russia)

Ruslan Ponomariov (Ukraine) - Lazaro Bruzon Batista (Cuba)

Vassily Ivanchuk (Ukraine) - Bu Xiangzhi (China)

Vugar Gashimov (Azerbaijan) - Peter Heine Nielsen (Denmark)

You can follow the games on the official website.

The top three finishers in the World Cup will play in the next World Championship.

Image by http://chess.ugrasport.com/