Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

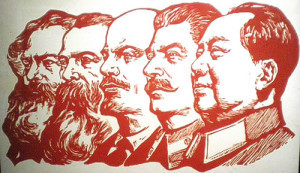

After the 1949 defeat of the Chinese Nationalists at the hands of Mao Zedong's People's Liberation Army, the newly-proclaimed People's Republic of China (PRC) established friendly relations with the Soviet Union. The fact that the Communist Party of China and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union shared a Marxist-Leninist ideology kept the two countries closely-aligned soon after the PRC was founded. But as China gained more power vis-à-vis its neighbors, trouble was just over the horizon.

The beginning of the 1960s heralded a new phase in Sino-Soviet relations. Ideology was at the crux of the issue, with China and the Soviet Union both vying for the title of leader of the communist world. China's economic reforms, which paved the way for a détente with the United States as well as greater participation in the global economy, were anathema to the Soviets during the Cold War.To make matters worse, territorial disputes, the most severe of which occurred over the island of Domansky (Zhenbao in Chinese) in the Ussuri River on China's border with the Soviet Union, nearly plunged the two countries into all-out war.

Helmut Sonnenfeldt, John J. Taylor, and Richard Solomon were American diplomats who witnessed firsthand the growing rift between China and the Soviet Union. All offer unique insights into why the two countries drifted apart and how the growing divide influenced the national security strategy of the United States. This account was compiled from interviews by ADST withHelmut Sonnenfeldt (interviewed in 2000), a member of the Office of the Director for Soviet Foreign Policy at the State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) from 1961 to 1969, John J. Taylor (2000), a Political Officer in Hong Kong from 1970 to 1974, and Richard H. Solomon (1996), a staff member of the National Security Council, Asian Affairs, from 1971-1976. You can read the entire account on ADST.org.

This account was compiled from interviews by ADST withHelmut Sonnenfeldt (interviewed in 2000), a member of the Office of the Director for Soviet Foreign Policy at the State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) from 1961 to 1969, John J. Taylor (2000), a Political Officer in Hong Kong from 1970 to 1974, and Richard H. Solomon (1996), a staff member of the National Security Council, Asian Affairs, from 1971-1976. You can read the entire account on ADST.org.

SONNENFELDT: China had become Communist in 1949. At that particular time, they were friendly with the Soviets, although we soon learned that even then there were some underlying frictions; but they still were pretty close.

It was the general assumption (now borne out by the Soviet archives and various other materials) that the Korean War was started by the North Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, with Soviet support, maybe even as a Soviet stooge. In fact, it was more complicated than that; there was also Mao Zedong's support.

After the Chinese came into the Korean War in 1950, and Soviet MiG fighters and MiG pilots were involved almost from the start, it all looked like a coordinated Sino-Soviet war with the U.S. But the long, bloody deadlock eventually led to an armistice after Stalin's death in 1953. Korea remained split along the 38th parallel.

We saw differences between the Soviets and the Chinese, including on the question of nuclear war. A colleague of ours, Donald Zagoria, was at CIA doing the same sort of thing that we were doing.He produced a thick volume, classified at the time, in 1956 or '57, showing the symptoms of major conflict and disputes between the Soviets and the Chinese. It was later published (under the title "The Sino-Soviet Conflict 1956-1961.") The CIA took out some classified material, but then released it, and it was a sensation at the time.

I was conservative; I accepted the notion that Marxist-Leninists had disputes, and even killed each other over them. But in the end, they believe in the same thing; so we ought to be very careful before we assume that there was a real conflict between the Soviet Union and China. A lot of other Sovietologists of what you might call the "hard line" school thought this conflict was unlikely, or may even be a trick to lull us into some false sense of security.

I think that the Kennedy administration came in very much concerned with our relations with the Soviets and very much concerned about our not doing as well as we should. The idea of getting America moving again was central to Kennedy's programs - at least they thought it was a good political tack to take - but their perception was that we were in serious difficulty with the Soviets. The Berlin crisis had been going on, and we had earlier in 1960 the U-2 episode. So relations were in pretty bad shape.

Also, somebody showed John Kennedy a long speech that Khrushchev gave, I think, October of 1960, a very famous speech... he talked extensively about wars of national liberation, delivered at a gathering of the international Communist movement, which increasingly had become a forum for Soviet and Chinese dispute.

Kennedy had made his principal Cabinet people - not only those dealing with foreign and security questions - read that speech by Khrushchev because he thought that was going to be the key problem, in addition to the threat of missiles, that we were going to have to face. The speech suggested a Soviet push, and at that time it was still believed to be a Sino-Soviet push, to contest the United States all around the world, including in Southeast Asia. The Administration then produced programs for counter-insurgency training - it wasn't called counter-terrorism, that's the term we use now.

Some of us felt that Khrushchev's speech might actually have as much to do with the emerging contest with China as with a threat and challenge on a global basis to the United States. The Russians and the Chinese were beginning to contest each other for leadership in the international Communist movement, and in the Third World - in Africa and elsewhere. But in Kennedy's view, Khrushchev's speech represented a big challenge.  In fact, the first big paper on a Sino-Soviet split, or potential split, or emerging split, was produced at the CIA in the Office of Current Intelligence by a man named Donald Zagoria. It was a long study, examining in the most meticulous fashion every statement, every utterance, every rumor, every inference. He came up with the proposition that this relationship was not going to be stable and was going to be more and more difficult.

In fact, the first big paper on a Sino-Soviet split, or potential split, or emerging split, was produced at the CIA in the Office of Current Intelligence by a man named Donald Zagoria. It was a long study, examining in the most meticulous fashion every statement, every utterance, every rumor, every inference. He came up with the proposition that this relationship was not going to be stable and was going to be more and more difficult.

Yes, we were keenly interested in the possibility of a split. Of course, by '61, '62, some of this became more and more apparent. In fact, after the Cuban missile crisis, Mao was very critical of Khrushchev's concessions. More and more of this was buried in esoteric publications and utterances, and the rumor mill became more and more obvious and clear.

Now, the policy inferences to be drawn from that weren't, strictly speaking, our business in INR. Secretary of State Dean Rusk and a lot of others were very skeptical about what was being put out on the Sino-Soviet split; they were interested, but they were skeptical.

They thought maybe it was a deliberate ploy by the Russians and Chinese to mislead us. Therefore, while we had some contacts with the Chinese - rather formal ones because of various issues about missing people - it wasn't really until Nixon came in that the inferences were drawn from this Sino-Soviet gulf that was widening and deepening every year, that led to the opening to China. But that was ten years later.

In the period we're talking about, the early 1960s, it was much more a matter for experts, not only in the government, but there were scholars who were tracking the relationship and were publishing things about it. I think on the whole, the policy people in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations were skeptical about making too much of this.

I think in China, as I think in the Soviet Union by the mid-to-late '60s, there wasn't much left of communism as a mobilizing idea, but there was still some. In China, there's very little of it now. I think something like national pride, reminding people of the terrible humiliations that they say they suffered for a long time, is a mobilizing force.

In the case of Russia, in terms of ideology or values that people are eagerly attached to and that have a mobilizing effect, I think by this time, they were getting more and more moribund. I guess they still thought of themselves as a leader of some global movement, and still thought of themselves as being a kind of model for the Third World.

TAYLOR: It was a time of major upheavals in world politics. At the beginning of 1969, Sino-Soviet tensions had almost broken out in actual warfare. Skirmishes had broken out on the Sino-Soviet border with heavy casualties along the Ussuri River. By early 1970, the Soviets were suggesting to us and to some of their Eastern European allies that they might have to use nuclear weapons to take out the Chinese nuclear facilities. Moscow expected that these comments would get back to the PRC, which they did. Kissinger for one passed them on. Dean Acheson had, many years earlier, predicted that someday the Soviet and Chinese communists would split. Twenty years later it was happening - and in a dramatic fashion.

Moscow expected that these comments would get back to the PRC, which they did. Kissinger for one passed them on. Dean Acheson had, many years earlier, predicted that someday the Soviet and Chinese communists would split. Twenty years later it was happening - and in a dramatic fashion.

The split did not happen overnight; it had been developing over a decade. The first clear evidence came in the ideological rhetoric, which emanated from each camp in 1959. In 1960, Khrushchev tore up Russia's agreement to assist the PRC, most importantly with help in the development and production of nuclear weapons.

In the mid-1960s, however, the PRC again adopted radical internal policies - the Cultural Revolution and the Communes. Mao felt it was necessary to purge the party of its more moderate elements and the bureaucracy in order to insure that the PRC would not follow in the Soviet revisionist footsteps. Soviet "socialist imperialism" became, in his view, an enemy on par with the U.S. or even worse.

Skeptics abounded on the extent of the riff. For example, as mentioned, many in Taiwan considered the argumentative rhetoric to be a subterfuge to mislead the West. Most China experts in the West, however, saw the seriousness of the dispute. We saw it as a personal and ideological quarrel but also a national rivalry for influence, which reflected some important differences in national interests.

In one effort to "leak" their position, the Soviets even sent a journalist - actually a KBG agent - to Taiwan to talk to Chiang Ching-kuo (politician, son of Chiang kai-shek) about what might happen if they (the Russians) attacked the mainland. The Soviets again expected that this exchange would get back to Beijing, put the PRC on edge, and perhaps encourage some anti-Mao thinking in the Chinese leadership.

By 1969-70, the Soviets believed an opportunity had emerged to make mischief by playing off a disaffected part of the PRC leadership against Mao. In fact, a grievous split had developed in the Chinese leadership that was not readily apparent.

After Nixon's inauguration, the beginning détente between the PRC and the U.S. gave momentum to this split. By 1971, the Soviets were apparently having secret exchanges with Lin Biao, the PRC defense minister. Speculation was rampant on where the PRC was going internally and externally.

SOLOMON: My second stint in Hong Kong was January through August of 1969. The Cultural Revolution began in China in terms of a leadership dispute in the fall of 1965. That's when we began to see overt political tensions. It actually had its origins in the failure of the Great Leap Forward, and Mao's loss of influence and support from his other colleagues that had come out in the early '60s. But we didn't see it at that point. It hadn't taken on the form of the Cultural Revolution. The first time I was in Hong Kong (1964-65), the early phase of the Cultural Revolution was just beginning. The second time I was there, in 1969, it was a matter of major purge, massive campaigns, and real violence, only some of which we could see from the outside. But what came to a head in the summer of 1969 was the growing tension between China and the Soviet Union.

But we didn't see it at that point. It hadn't taken on the form of the Cultural Revolution. The first time I was in Hong Kong (1964-65), the early phase of the Cultural Revolution was just beginning. The second time I was there, in 1969, it was a matter of major purge, massive campaigns, and real violence, only some of which we could see from the outside. But what came to a head in the summer of 1969 was the growing tension between China and the Soviet Union.

In the summer of that year there were major border clashes along the Sino-Soviet frontier that had their precursors in the early part of 1969, and all the propaganda coming out in Hong Kong that summer asserted that the Chinese people should get ready for war with the Russians. The propaganda appeal to "get ready right now" was just one indicator of the sense of intense urgency about the growing tensions between China and the Soviet Union.

The big issue was that Mao was a very confrontational personality. He differed from the traditional Chinese political culture in that he would press confrontations, whereas the traditional Chinese approach was to try to minimize them, to submit to authority, and to avoid confrontation. Mao, however, decided to take on Khrushchev frontally, which he did after Khrushchev's anti-Stalin speech in '56. One could see that situation in terms of the evolving Sino-Soviet dispute.

What that meant for China taking us on, in terms of Vietnam, was unclear. And some people said, "Oh, the Chinese are going to take us on. They have all these internal problems, so they'll try to externalize all this conflict by confronting the United States." And others said, "No, no, they've got tremendous internal difficulties, they've got their confrontation with the Russians; they can't take us on as well." There was real division of opinion on that issue.