Recently, I attended the Thesis Exhibit of the graduating class of the Masters of Fine Arts program at Columbia University. The thesis exhibit is held every year at The Emily Fisher Landau Collection's exhibition space on Long Island City. I was there primarily as the parent of one of the graduating students, Julia Sherman. As an artist myself, I had a great interest in seeing the work of the new generation of artists as represented by the small, but elite group.

Graduate students in Columbia's fine arts program are working artists who have had some experience creating and exhibiting their work prior to graduate school, and their objective in pursing a higher degree is to spend time surrounded by an artistic community, where their work will be both critiqued and supported by their professors, fellow students, as well as visiting artists, curators and scholars. It is an intense experience in which an artist must express, in verbal terms, a strong theoretical foundation for the choices they make in producing visual art and has no choice but to clarify their thoughts along the way. The Thesis Exhibit is the culmination of this two-year program.

In it, I saw diverse responses to the world we live in, some focused on specific social and political issues such as war or feminism, some more personal in their approach, some more abstract in their approach, but all firmly rooted in the present. Yet, in many installations, I could see a connection to a distant past -- to Old Master art. Even though these young artists were looking for their own place in the present moment of the narrative of art history, they are living through a time that bears many similarities to the times that the Old Masters lived in and are reinventing the aesthetic that went along with it.

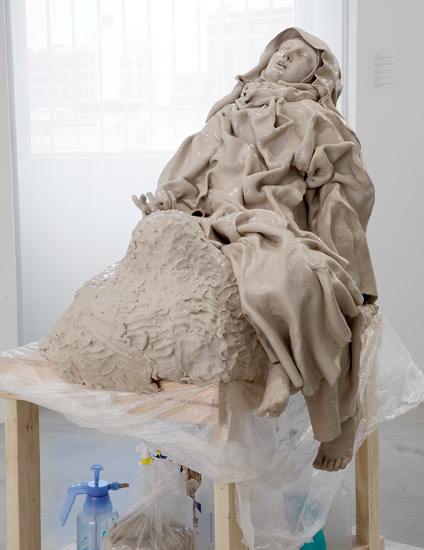

An example would be the "Sweaty St Theresa" by Brie Ruais. In it, she responds to Bernini's "St Theresa," challenging the tradition of the male as artist and the female as muse/ model/saint.

Bernini's piece largely piqued my interest as a feminist and as a sculptor working with clay's relationship to the body. Bernini's "Ecstasy of St. Theresa" is charged, for me, with questions pertaining to female sexuality and erotic depictions of women by male artists. I wanted to interpret her prolonged moment of ecstasy with wet clay that had to be maintained throughout the lifespan of the piece. I was interested in the way the wet clay itself brought a visceral sensuality to the piece, for the way it both related to the Bernini sculpture and is at odds with the marble he used. In the end, the piece, for me, had so much to do with this idea of keeping the female subject malleable through the use of wet clay, allowing her to flux, fluidly changing as time passed. Bernini's iconic St.Theresa had been transformed into a fluid subject, representing that when gender roles and sexuality remain fluid, they can never be fixed, pinned down, or consumed.

The theme of human frailty was at the core of Master art of the 17th century. In Dutch and Flemish still life painting of that time, flowers were always accompanied by insects that preyed on them, dew drops that dessicated them, fallen petals or leaves that reminded the viewer of the inevitability of the passage of time.

Brie's piece gives a palpable physical reality to that theme.

The demanding nature of its maintenance, the vulnerability of the material, the ephemerality of the piece does relate to themes of human frailty. My relationship to the piece changed over time, but remained intimate and sometimes burdensome. My presence was always necessary; I had to bring her both into and out of existence. The decision to float with her down a river and to release her was twofold: The piece had to reach a point of deterioration in order to breakdown both the material and the icon. Floating with her, pouring buckets of water over the sculpture in an effort to keep the clay moist despite the heat, watching parts of her habit and garment tear apart, seeing her face crack, her fingertips dry out, was like bringing her to her end. It was the ultimate breakdown of what is fixed and predictable. I hope she made it out to the bottom of the ocean.