In November, Freestyle Photographic Services, the US distributor for the Holga toy camera, announced that the Holga factory had ceased production of the iconic medium format legend - permanently.

Just another casualty of the age of all things digital. Yet something felt differently this time, at least to me. I've lived through a great deal of camera discontinuation announcements over the past decade, but none were as eerie to me as this one. I think that is because for the past few years one of the major analog film cameras still being mass produced was the Holga. It's death is significant. Sure, the Holga was not the last kid on the block, but in some ways I cannot help but feel as though it was somehow the last of a certain kind. At least for me the passing of the Holga is truly the end of an era in analog photography. Perhaps 2015, in retrospect, will be seen as the beginning of the end for analog photography - for real this time. Only time will truly tell.

Holga has also announced that all tooling for the Holga cameras has been destroyed and nothing is available for sale. I guess this rules out an Impossible Project kind of savior from, well, saving us. Truly a sad announcement.

To make this solemn occasion, I wanted to interview a photographer who has made the Holga truly shine. Enter Liz Potter. Liz has used Holga since 1990 and had produced some truly wonderful work. Here's our conversation about this unforgettable camera and its ultimate demise.

Michael: Holga discontinued production of their cameras in November. A classic is gone, forever. How do you feel about this? Will you stock up on them?

Liz: I'm sad that they're coming to an end, but at the same time I have to believe that something equally artistically loose and fun, that taps into people's desire to create simply, will arise. Before I bought my first Holga in 1990, everyone interested in alternative processes and vintage cameras were on the hunt for Diana's, and now they can be bought so easily online because of Lomography's version of it. So maybe there's hope for a "next generation" Holga.

Michael: Analog photography has been dying almost as long as I've been shooting; yet it has hung on. Now, things are picking up pace a little and the real end could be near. What will the end of analog photography (at least in any kind of mainstream, affordable way) mean to your own personal work?

Liz: I try not to think of the end, but I know it's coming. Since I shoot 120 and use the 12 shots per roll carefully, I don't burn through film like when I shot 35mm. I hope that my stock piling of film, and the resources to get it will keep me in business long enough to figure out my next step. Besides Holga photography, I'm interested in alternative processes and have friends who teach them, so maybe I'll go even deeper into history and start shooting wet plates or something. Who knows!

Michael: What attracted you to the Holga initially?

Liz: I was introduced to the Holga in 1990 at the Maine Photography Workshops, and I was immediately taken with the total lack of control with the technical aspects of the camera. It's a camera meant to be used intuitively, and that captured my imagination. I liked how it was unruly and not precise in clarity or frame composition. It took the focus off the technicality of capturing an image and freed me up to just "feel" the scene. Eventually I learned to use it like any tool- is there enough light, when I might be able to get away with a flash and still get an interesting image, how to frame something and actually know most of what would be in the shot. I always laugh when people say it's just "a lucky shot" with Holgas because while those happy accidents do exist, the Holga can be tamed and the photographer can actually use it functionally, it's not always a guessing game.

Michael: Most of your work with the Holga seems to be monochrome. Why have you not taken advantage of color?

Liz: I think I might have dabbled more in color if I had been able to print my own work, but color printing is too hard for me and I don't have access to a color lab. In the past 25 years, I have only shot maybe 3-4 rolls of color. It just doesn't speak to me the way black and white does. When I see something in front of me, I see shapes, atmosphere, a movement to capture, a moment to grab on film, I see contrast, I don't see color.

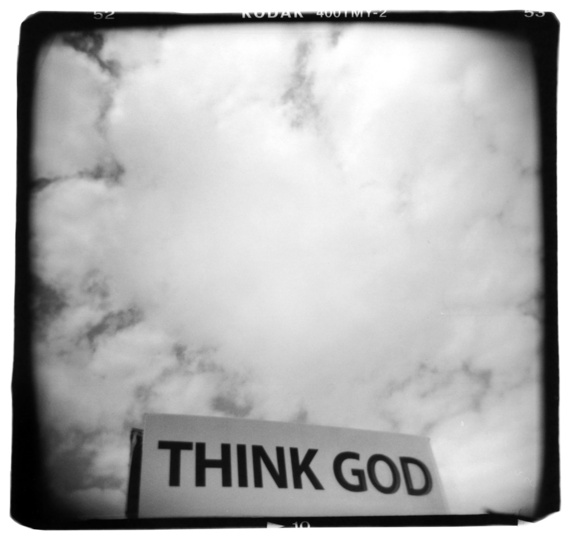

Michael: You mentioned that you made your own negative holder; can you tell us a little bit about that and why you process your own work?

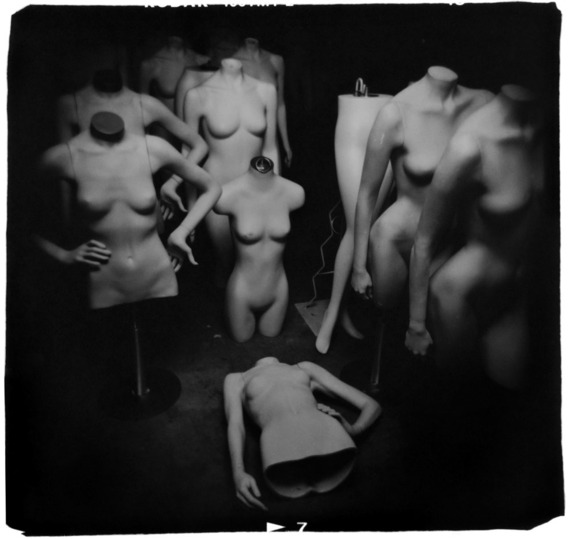

Liz: In college I was trained to crop in the lens, not in the darkroom, so this pure way of image capture dictated the way I printed. Always full frame. When I started printing 120 I liked seeing the black border because the vignette of the negative showed more dramatically. To get a border means having to file out a 120 carrier, so instead, I made one with museum board and gaffers tape. I like the organic shape it gave the square image, and also that it allows hints that the photo is on actual film by allowing numbers or even "Kodak" to show on the borders.

I process my own work because I think my photography is 2-part: captured on film, teased out in the darkroom. Holga negatives are pretty rough, some are thin, some are dense, there's a lot of dodging and burning on some images and I like to have control of that. There's something so indescribably beautiful about a fiber print that someone carefully developed in the darkroom.

Michael: Who inspires you when it comes to toy camera photography?

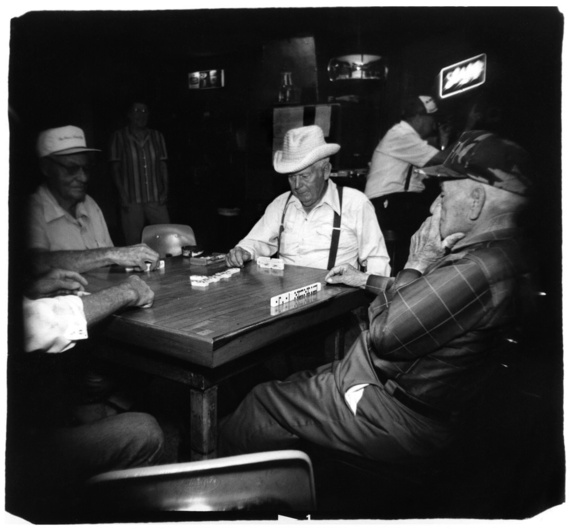

Liz: I'm embarrassed to admit that I'm not familiar with many toy camera photographers. My main influences have been Henri Cartier-Bresson for his genius in telling stories through a single image and his unbeatable composition, Mary Ellen Mark for her ability to capture people in such poignant ways, Diane Arbus for making the strange so beautiful, Josef Sudek for his gorgeous, moody photographs, and more recently I've been exposed to the work of Vivian Maier, whose work inspires me because of her fearlessness in getting an image, as well as her off-center way of seeing the world.

Michael: How has the Holga helped shape the way you see?

Liz: I go through periods of not shooting, but when I do pick up the camera and start the hunt, I pay attention to scenes that are compelling even if recorded simply with the lens of the Holga. My favorite images are those that tell a story or make the viewer wonder what's going on, so I look for those circumstances. If I witness something that would have possibly made for a great photo, and I don't have my camera, I look for that same type of feeling in the future when I do have my camera. My favorite college professor, Dennis Darling, taught me that. He said that often a scene will be repeated, you just have to watch for it.

Michael: I like that, it's good advice. Do you work with the Holga exclusively or do you also use more mainstream cameras also?

Liz: Somewhere in the late 1990s, I stopped shooting 35mm and exclusively used the Holga. Sometimes I think about loading up my old Cannon AE-1, but then end up picking up my Holga instead. The only digital photography I do is product shots for another business, and snapshots. I don't do much myself, but I love a lot of the camera phone work people are doing, so I'm definitely not against digital photography at all, it's just a different medium.

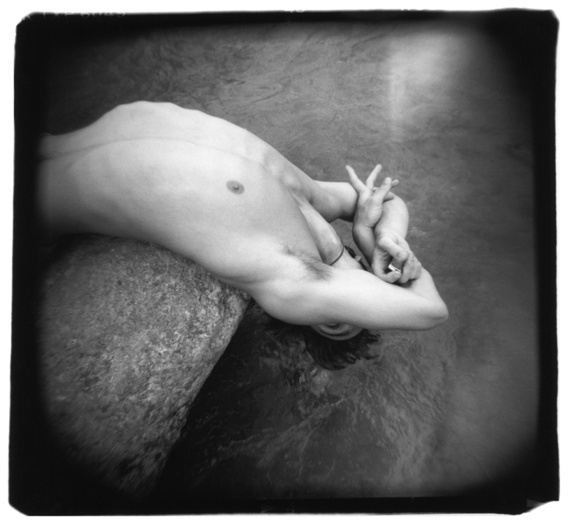

Michael: I certainly see the Arbus influence in these last few images. I love them. Today it seems many people are content to achieve this "Holga look" digitally with apps like Instagram. How do you feel about this? Do you think the Holga offers something that a digital filter cannot and, if so, what is it exactly?

Liz: The "Holga look" is cool; I don't blame people for wanting to mimic the dreamy appearance. Unless it's done very well, most people can tell a difference between an app generated vignette and a film version. The Holga is so quirky that lighting, speed, the lens - they all affect the images in different ways, so the true Holga look can't be duplicated.

The digital filter is flat. To me it looks added. I don't think I'd be able to duplicate the look of any of my Hoga photos by shooting a straight photo and adding the vignette because of the way I see with a Holga versus other cameras. When I shoot a Holga, my focus is always the center, knowing that the edges will fall off. When I shoot with a regular camera, my eye will automatically scan the entire frame, edge to edge, to see if that is what I want in the photo. My mind is looser with a Holga.

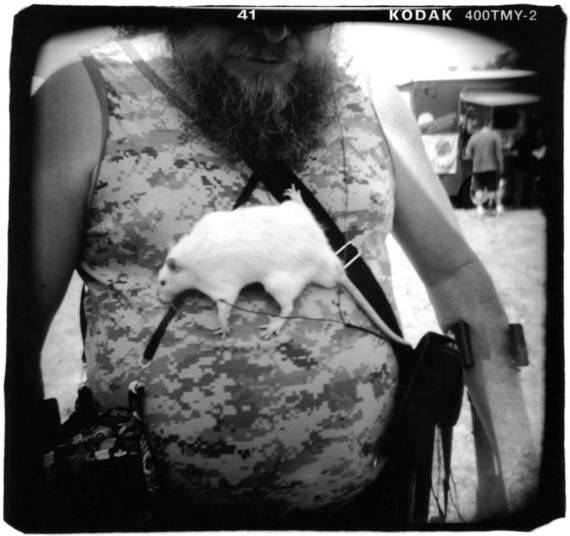

Michael: A lot of animals appear in your work. Is this simply a product of your physical environment, or do you seek them out for some reason?

Liz: I'm an animal lover, and animals never want to know what you're going to do with the photo you just took of them! But, you're also correct that they're in my work as a product of the environments in which I put myself.

Michael: What's next for you in photography, now that we are entering the post-Holga era?

Liz: I have no idea! I think as long as there's film, and as long as one of my five Holgas are working, I'll be okay. I'll continue to live in denial that there's actually an end and hope that when it comes I'll be ready for something else.

Liz Potter lives in Austin Texas where she continued to live after graduating from the University of Texas with a degree in Photojournalism in 1990. Using the Holga camera and black and white film, she has freelanced as a photojournalist, shown in galleries, but currently uses the camera and darkroom purely for personal gratification. Her main line of work today is designing and making purses. Click here to view more of her work on her website.

Michael Ernest Sweet is a Canadian writer and photographer. He is the author of two street photography books, The Human Fragment and Michael Sweet's Coney Island, both from Brooklyn Arts Press. Michael's concise guide to street photography appeared as a feature supplement in the January edition of Digital Camera Magazine, currently available on newsstands worldwide.