WHAT FOOTBALL CAN TEACH CLASSICAL MUSIC

Whether or not you are interested in football, you undoubtedly noticed a few weeks ago that the University of Missouri football team's threatened boycott of their game forced the resignation of their president, Timothy M. Wolfe, and the chancellor, R. Bowen Loftin. As the New York Times reported, "The prospect of a strike by a team in the country's most dominant college football league, the Southeastern Conference, drew national attention, and officials said that just forfeiting the team's game Saturday against Brigham Young University in Kansas City, Mo., would cost the university $1 million." That would be $1 million for one amateur football game being broadcast on national television.

Many have praised the power of the team to force out what seemed to be an administration that persistently was unresponsive to the profound racial issues on the campus. And who would not praise those brave students? Even the White House noted the power of "a few people speaking up and speaking out" and having "a profound impact."

The other day, the New York news channels were all abuzz on the firings of Rutgers University's football coach, Kyle Flood, and its athletic director, Julie Hermann. Flood's buyout has been reported at $1.4 million. His annual salary of $1.25 million was among the lowest in the Big 5 conferences. The next person to hold the job will get a lot more. "We look at this on a five-year basis, and as an investment in our future," said Rutgers's president, Robert L. Barchs.

Investment.

Anyone who watches football or the evening news has also noticed that Pfizer has launched a new ad campaign for Viagra that starts with a beautiful woman wearing an oversized football jersey. She looks longingly into the camera and says, "Watching football with your man is great, but cuddling after is great, too." Then she tells us what happens to most men over 40. After seeing this commercial many, many times, I started to imagine another ad campaign.

A beautiful woman is on a bed, wearing a little black dress, high heels, and a string of pearls. She looks at the camera and says, "Going to hear Lulu at the Met with your man is great, but cuddling after is great, too."

And then I wake up.

When television was young and everything was available on three networks, it seemed as if television would be the porthole through which all things would be seen: cooking shows, puppet shows, farming shows, old people talking ("Life Begins at 80"), history shows ("You Are There"), news for a total of fifteen minutes, symphonies (NBC had a symphony orchestra conducted by the greatest conductor of the era, Arturo Toscanini), operas (NBC had an opera company!), dramatic shows ("Playhouse 90"), variety shows ("The Ed Sullivan Show") and sports (my favorite being female roller derby).

Somewhere during that time, the president of the American Federation of Musicians, James Caesar Petrillo of Chicago, worked hard to insure that professional musicians were being paid better and were being protected from many of the unfair practices in the pre-union days of music (meaning all of history prior to 1940). No one can fault him for that. He also did something else. He stopped all commercial recording in America for a number of years in order to get higher wages. The work went to Europe. He also famously said that the Chicago Symphony would never be on television. I believe he used the "over my dead body" phrase. What he and his supporters believed, and many still do, is that the way to insure an income for professional musicians is to limit their accessibility in recording and broadcasts, ("Support Live Music!" was a motto) thereby preserving their value in live concerts. The union also did not want amateur ensembles to infringe on the territory of the professional musician. It was seen as costing jobs.

Sports went the other way. Instead, sports wanted kids to play early and keep on playing--with their parents as cheerleaders. Amateur sports became a huge business with a gigantic audience. Amateur football not only feeds professional football but billions of dollars are currently made from people who are happy to put down their money to support the entire gamut: from peewee football to the Hall of Fame. Forget Golem and Bilbo Baggins. Forget Fafner and Hagen. Vladimir Putin 'stole' Robert Kraft's Super Bowl XXXIX ring. He still has it! (To those of you who think I was referring to Igor Stravinsky's recently deceased assistant, Robert Craft, Mr. Kraft is the CEO and Chairman of the New England Patriots. That's a professional football team.)

And for all the clever links forged between the NFL, our armed forces, and all things American and sexy--Viagra--it is music that usually comes to the rescue when the world falls apart--which seems to be a weekly occurrence. And except for an occasional "feel good" story at the end of the half hour national news that shows how music transforms lives, it is football that dominates television. But you have already noticed that.

I wonder what would have happened if James Petrillo and his supporters had gone another way. What would Juilliard and the Curtis Institute of Music be receiving for their regular television broadcasts? Would a kid who carries a cello on to the school bus be a hero, like the one who plays on the football team? Would we be listening to great amateur orchestras playing a Beethoven symphony for the first time? I well remember what the Yale Symphony sounded like when I was its music director in the late 1960s. On December 13, 1969, when we performed Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, it was a communal discovery, one that made the standing ovation not only necessary, it was involuntary and unanimous. Was it better than, say, a performance by the New York Philharmonic? No and yes. It was a life-and-death performance and it was incomparable.

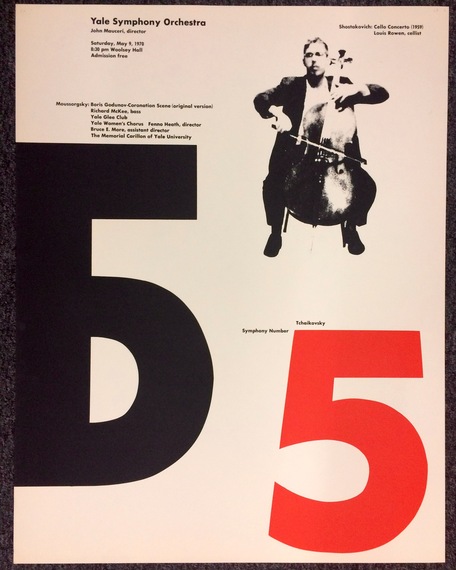

Because the Yale Symphony Orchestra is celebrating its 50 anniversary this year, and I have been asked to conduct it again, I have also been thinking about the power of that orchestra during a time of tremendous unrest, similar in its way, to the unrest at Yale right now --not to mention the University of Missouri. The President of the United States had been assassinated. Then his brother and the leader of the civil rights movement were murdered. The United States was in an incomprehensible and undeclared war in a far-off place called Vietnam and we were all liable to be drafted at any moment. Wait for the mail to be delivered and see if your life would be forever changed and do that every day for a few years and imagine what that does to a campus.

(See if any presidential candidate suggests reinstating the draft and then perhaps you can picture 1970.)

On April 30, 1970, President Nixon announced that he had authorized U.S. combat troops into Cambodia as a pre-emptive strike against the North Vietnamese. In other words, we began to bomb and kill people in yet another country. The effect on America's campuses was immediate. On May 4, four students were shot and killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. More than 450 Universities and high schools just stopped. No classes. No activities, except of course marches, rock throwing, and tear gas ... and a scheduled concert by the Yale Symphony for May 9.

The Yale Symphony is Yale's undergraduate orchestra. It was and is a volunteer organization. No one got course credit for it. The concerts were given free of charge. They were consistently full, with 2,500 students attending them, many arriving an hour early to get the best seats. The then university president, Kingman Brewster, Jr., and his wife, Mary Louise, would regularly attend, sitting in the first balcony--second row, on the aisle. Every student felt they knew and liked him, and his presence made the YSO the place to go.

The repertory we played then was astounding, even now, a half century later: Living composers like Stravinsky, Cage, Bernstein, Ligeti, and Messiaen, mixed with first New Haven performances of scores by Ives, Mahler, Wagner, Debussy, Schoenberg, and Hindemith. And yes, Beethoven, too. Undergraduates had become pretty blasé about the football games and the stats at that time said that more undergraduates were attending Yale Symphony concerts than were buying tickets to football games.

Imagine.

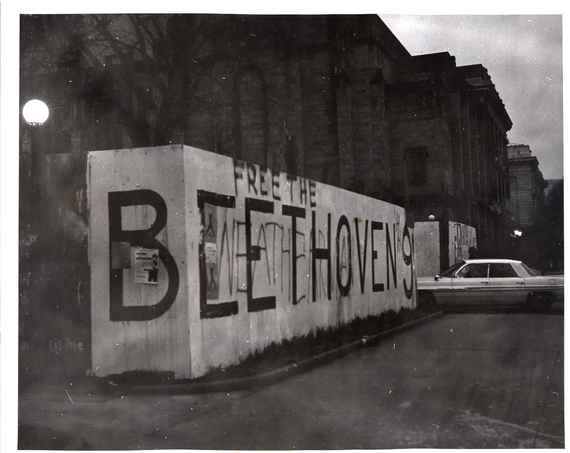

There had been a huge rally on the New Haven Green on May Day, 1970 in which U.S. imperialism and institutional racism were called into account. Black Panthers, the FBI, and Hell's Angels were all present in our little town. I well remember standing before the Yale Symphony during those heated days when the university was ostensibly closed. I said it was their choice whether or not to give a concert. I perfectly understood whatever decision they would come to but they had to come to it together. There had to be an orchestra on the Woolsey Hall stage, not part of it. I walked around the block and came back fifteen minutes later.

The students had voted. Only one person did not want to give the concert. She was the principal horn player and there was no way we could play Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony without her. Ultimately a compromise was reached. Yes, we would play the concert. We would also collect money for the Calvin Hill Day Care Center. The university agreed to match every donation, dollar for dollar. Calvin Hill--yes, a football star, who had graduated the year before--returned from his new job with the Dallas Cowboys to encourage the creation of the center "to ease the financial strain on many Yale workers."

And so, on Saturday night May 9, 1970 a packed Woolsey Hall heard music. To the astonishment of the administration and faculty, one thing functioned on the campus: a classical music concert played by a volunteer orchestra. Music reminded everyone of what makes us human and what can bring us together.

All of that brings me back to college football, a million dollars a game--and amateur music. The United State of America has the greatest conservatories in the world. Our student orchestras are simply astounding by any standards. Maybe it's time to consider amateur sports as another way for us to approach our young performing musical artists. In the short run perhaps their presence in the media might mean some people will prefer their performances to professional orchestras. I doubt it. In the long run, we just might see something truly amazing: We could make our young musicians the heroes they are and we could sow the seeds of an audience that grows up with our children. Hockey moms? Sure. Symphony dads? Sure. Music families? Absolutely.

Discuss.