This article by Chas Smith originally appeared on Fatherly:

The New York Times' CJ Chivers is one of our greatest living war journalists. His 14 years in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria set the mark for how modern conflict is covered. And now he is done. Esquire published a piece, "Why The Best War Reporter in a Generation Had to Suddenly Stop." It told the story of a remarkable career but did not, satisfactorily, deliver on its promise of why he had to suddenly stop. And, baby, I needed satisfaction.

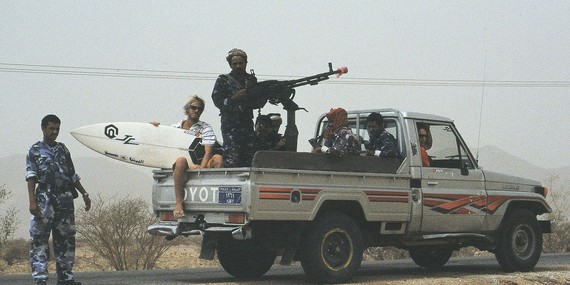

Because I was, briefly, a "war reporter" too, albeit maybe the worst in a generation. My career was as thrilling as it was accidental. I became fascinated in the Middle East as a child because my uncle was tied up in Iran-Contra and friends with Ollie North. I studied in Egypt as an undergrad and sprinted, with two friends and a cameraman, to Yemen after 9/11 because I read Osama Bin Laden hailed from its hills, and also because I cover surfing and Yemen had miles of un-surfed coast. Al-Qaeda chased us through remote towns, wagging guns and sometimes firing them, and I felt bigger than life itself and better than you.

After Yemen it was Syria, Somalia, Colombia when it was bad, Azerbaijan, Russia, deep Mexico when it was worse, etc. Anywhere with either an active insurgency, criminal uprising, or hostile government. Of course, I am being liberal with my use of the word "war" but post 9/11 what did that even mean anymore? I wrote about my asymmetrical adventures for bastions of shallow, like Vice, Stab, Oyster and Flaunt. I tried to touch on refugee crises, death tolls, and socio-political/human impacts of a world undone, but often I veered sharply into wildly unrelated topics like obscure British rap in Somalia or wartime fashion. Because I am also shallow.

The author, in Lebanon, with the leader of the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade

Then Israel invaded Lebanon in 2006 and the same two friends and I sprinted in. For the first time, we were shoulder to shoulder with real war reporters, in a proper declared war. We watched the CNNers and FOXers strap on helmets and buckle up flak jackets and I openly mocked them, especially, for writing "TV" on their cars in massive letters. Fortune favors the bold in the Middle East! And so we rode scooters deep into Hezbollah's neighborhood and almost got flattened by an Israeli bomb. Then we got shot at by the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and then got kidnapped by Hezbollah. Our experience was cinematic. Slapped around, tossed into the backseat of a Mercedes and blindfolded. Gun pressed to temple. Tossed in a dungeon with no light and a bloody mattress. Interrogated and released in less than 24 hours. Fortune favors the bold?

I didn't cover war after that. I meant to but life took me to surf coverage full-time and I didn't complain. Palm trees, mai tais and salty warm water make for a very fine shallow life. And surf led to me meeting and marrying a gorgeous blonde and having a gorgeous blonde baby girl. I wrote a book about Oahu's North Shore, comparing it to war, and then thought, "I miss real war." When Russia stacked troops at the eastern border of Ukraine and separatists firebombed the night, I quickly booked a ticket to Kiev.

I wasn't scared when arriving, but felt very off while rolling through the capital's empty streets and make-shift checkpoints run by shifty men. I felt even more off booking a room at the Ukraine Hotel. It had been a morgue weeks earlier and blood still stained the carpet near the elevator.

Our experience was cinematic. Slapped around. Gun pressed to the temple. Tossed in a dungeon with no light and a bloody mattress.

Maidan Square, straight out the front, was empty but still smoldering. It was here that mass public protests led to the collapse of Ukraine's government, Russia's involvement and many deaths. A grey and steady drizzle painted the scene black. And why did I feel so off? Kiev is Europe, for pity's sake, not Syria or Somalia. Its lawlessness is measured but I could not shake my uneasiness.

Everything felt wrong and I was haunted because my baby girl was back home. To be far away from her, close to death, to tell stories of death, to potentially leave her fatherless, all felt like a giant sin. Had I forgotten how horrible it was in a Hezbollah dungeon with bloody mattresses? No. It was horrible, yes, but exhilarating because the only thing I had to lose at the time was a shitty ex-wife and she was the only person that I had to disappoint as well. Dying didn't matter. An awesome story did. But now I am helping write a gorgeous blonde baby girl's story too and, fucking hell, if I don't miss her every second she's not in my arms. So I didn't go to the eastern border where fighting was hot. I just went home.

Mr. Chivers did far better and far more and, of course, I am not comparing our experiences. He was an artist of the genre and committed in a way my pop interests would never allow. But he also had a family, 5 children, and one of them got hives before one of his recent deployments. When he got back, the hives went away. A doctor told him that it was an autoimmune miscue caused by terror because his son was afraid for his life. "A switch went off at that moment for me..." he told Esquire "...You know...I mean, I realized I couldn't do that to him. And for a few weeks, I quietly argued with myself about this and tried to find a way to mentally, to see if I could get the switch back into its old position. I remember lying in bed night after night saying, I think that's it. I think I'm done."

The view from the Ukraine Hotel after the riots that started the civil war.

And he was done. After returning from a trip from eastern Ukraine, the same eastern Ukraine where I never went, he asked The New York Times to be reassigned and has not been to a war zone since.

It is a tale well told but did me no good. He had 5 kids, all of them after he started covering war. He knew of the risks before the one developed a problem, no? He knew of the danger. So why now? Did it just congeal for him in a visceral way? That seems too simple and does not match with his overall game. He covered conflict like an artist, yes, but also like a scientist. The story points out Mr. Chivers was an ex-Marine, he knew more about guns, ammunition, artifacts of death and destruction than anyone and could piece together complex, unwieldy narratives using them as concrete markers. Again, the best of a generation.

I have always fundamentally believed a father needs to be bigger than life for his children. A father needs to perpetually exhibit a swashbuckling, devil-may-care attitude. Throwing caution to the wind, letting those little honeys feel this world operates in accordance with his will. And when it doesn't? It still does! Everything is always going to be ok! That is the role a father should play.

A father needs to perpetually exhibit a swashbuckling, devil-may-care attitude. Throwing caution to the wind, letting those honeys feel this world operates in accordance with his will.

I felt like I flinched in Ukraine. I felt like potential for dying and leaving my daughter without a father influenced my decision-making and made me feel mortal and how can a father be mortal? Still, there was no way I was going to push against it. There is no way I am going to push against it. I need my baby to be in my arms possibly more than she needs to be in them. But that feeling didn't smack of revelation. It smacks of inadequacy. So I shoved it down deep and hadn't looked at again until I read about Mr. Chivers.

And now it's all a freshly mixed up mess. Or maybe not. Maybe it is the simplest thing on earth and it just took this long to congeal. I will never ever put my self-interests in front of my daughter's nor will I put my esoteric thoughts on fatherhood. I had hoped Mr. Chivers would help me reconcile two irreconcilable things but I suppose I don't need them reconciled. Flinching is no longer just about self-preservation or cowardice. It is now my arm shooting across her little body when the car in front of us suddenly brakes. It is catching her when she slips off the monkey bars, even when I'm looking at college football scores on my phone.

Flinching is never letting her hit the ground.

(Unless CNN wants to pay me like Anderson Cooper. Then she can hit the giant silk Isfahan rug ($4.4m) out of central Persia that I will buy to cover it).

Chas Smith is a hyper-ironic surf journalist and bon vivant from Coos Bay, Oregon. He has written for Vice, Surfing Magazine, Stab Magazine, Esquire.com, and is the cofounder of Beachgrit.com. His book latest book is Welcome To Paradise, Now Go To Hell.

More stories you'll like from Fatherly:

Also on HuffPost: