What do Grammy-winning singer-songwriter John Legend and independent hop-hop artist Hoodie Allen have in common?

Besides being alumni of the University of Pennsylvania, they are both defectors from the corporate world, with the former leaving Boston Consulting Group in favor of a career in music, and the latter from Google.

While few can claim to rival Legend and Allen's daring career changes, fellow Penn alumnus Andrew Chung has a rare - and somewhat antithetical - story. The self-taught pop singer turned down multiple backing offers from record companies and artists in order to pursue life as a venture capital partner in Silicon Valley.

Even in the venture capital world, Chung still stands among the rare crowd. In addition to belonging to a small demographic (only 10% of VCs identify as Asian), Chung is a partner at Khosla Ventures, one of the few firms still heavily dedicated to sustainability and clean energy.

I visited Khosla's foliage-clad, wood-paneled (and exuberantly purple) offices to learn about Chung's journey in helping make the world a greener place - and how his inner performer influences his strategy.

From Harvard to Chinese Pop Star

Chung grew up in Chinatown, New York but moved to the safer Bucks County after a string of three muggings in five years. There he worked in his father's Chinese restaurant, where a particular frequenter took notice of his quantitative prowess.

"I was quick with numbers," he recounts, "the local town physicist noticed, and he would come every week to teach me math."

Chung picked up things with a mental acuity many years his senior. By six, he was well versed in geometry; by ten, calculus; and by twelve, relativity. By seventeen, Harvard took notice and soon he was studying Mathematics under its esteemed faculty.

Despite his prodigy-like sharpness, Chung's childhood ambitions were modest.

"Initially I was just concerned with getting educated in the right way and setting myself up for some future success," he says, "I was planning on one of the 'traditional' vocations - like being an engineer, a doctor or a lawyer."

Chung soon had a taste of the manifold possibilities waiting for him right off the trodden path. He launched his own e-commerce company the July after his graduation, which was acquired by a public company twenty-one months later.

Later in the same year, Chung got into contemporary Chinese music, dabbled in a Chinese-American singing competition and ended up winning the national contest. Three years later, he competed again in Hong Kong's version of the American Idol show and became one of the finalists among the 3,000 that auditioned. One of Hong Kong's most prominent record labels eventually offered to sign Chung as one of their stars, followed by two more backing offers from individual artists.

Each time, Chung turned them down.

"It was very hard. I came really close to signing my life away each time, and I'm glad I didn't."

Despite the promises of manufactured fame from a large record label's marketing budget, Chung was apprehensive of the personal and musical limits of becoming a pop singer.

"It's hard to have a family, it's hard to have a normal life...and it's not necessarily a life where you can just focus on music-making."

He adds, "My dreams and aspirations were pretty simple in retrospect since I didn't know what was out there. That changed when I got deeper in my career and realized what I could do to truly make impact and make value."

Unbeknownst to Chung at the time, his short-lived musical career would play a major role in his life as a venture capitalist.

Businessman by Trade, Performer at Heart

Chung eventually joined Khosla Ventures, one of the few venture capital firms still heavily committed to clean-tech investments.

"Part of this is because sustainability is a very hard space (for VCs)," Chung explains, "(it has) very long horizons, very large incumbents and political bureaucracy. It's also an area that a lot of VCs don't understand, and it's very capital intensive."

The capital required to create large-scale sustainability innovations comes as no surprise; after all, you are "building a plant, not a software app," as Chung remarks. Despite this, he still believes making the world cleaner and greener is one of the issues that people of our time can solve.

"The thrust of the revolution has to be a portfolio approach," he explains, "there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but technology is still the right way. If I could help (clean-tech companies) reach a point of commercialization, there is a potential to generate massive returns and massive impact for the society."

A major part of Chung's mission to make the world a better place by "enabling 5 billion people to live like 1 billion do now" is to hunt for "Black Swans" - companies that can potentially generate immense societal impact and disrupt entire markets.

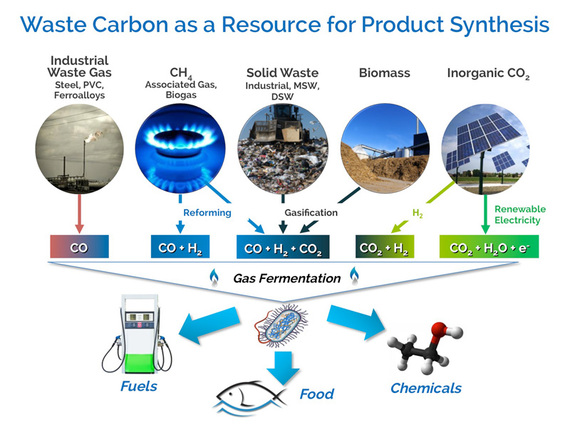

One of these companies is LanzaTech, a carbon mitigation company that captures toxic gases released in steel plants and converts them into fuel. Approximately 50% of carbon used in steelmaking leaves the plant as carbon monoxide, which is then combusted to form CO2, a major agent in causing climate change. LanzaTech captures these waste gases and ferments them with its proprietary microbe to generate bioethanol. In turn, every ton of bioethanol displaces 5.2 barrels of gasoline.

In fact, LanzaTech's recent partnership with the world's leading steel and mining corporation ArcelorMittal is expected to save 47,000 tons of ethanol per year, enough to power 500,000 cars with ethanol-blended gasoline - more than enough to power every motor vehicle in Luxembourg, where ArcelorMittal is headquartered.

Besides its societal impact, part of what excites Chung about LanzaTech also came from his background as a performer.

"My background in music and performances affected a lot of how I am as a businessman," he admits, "every engagement with a consumer, an entrepreneur or an investor is - in some sense - a performance. A lot of what I did as a performer was to train myself to be able to...make an emotional connection with a group of people."

Chung's ability to see and help craft emotional connection is central to his modus operandi as a venture capitalist.

"The reason we got deals between LanzaTech and BaoSteel (one of China's bigger steelmakers), where the latter fully funds commercialization and we don't have to put in a dime into building the steel plants, is because of an emotional connection." he says, "(BaoSteel) feels that the partnership is good for their country and good for their business."

It is easy to see why this might be the case: after all, even billionaire entrepreneur Richard Branson said announcing his partnership with LanzaTech was "perhaps the most important announcement that I've made in my lifetime".

The "Unknowable Upside" of Investing in the Future

Now, when Chung is not spending his time with his wife and daughter, serving on the board of nine companies, serenading Tyra Banks or singing Jason Mraz at conferences, he is envisioning the future.

"When I was in college, I had such a narrow view of what the world was. I grew up in a very enclosed environment. I had amazing parents who exposed me to a lot of resources to give me a chance to create a better life for myself, but it was still very narrow.

"Since I graduated in college, I've been exposed to a lot of cool things. What excites me is that it's actually impossible to predict the future. I probably thought that I have a much better sense of what I was going to do next when I was in college compared to now."

He adds, "The unknowable upside of putting out great technology with an emotional appeal to a market that accepts it excites me. That combination creates revolutions."

As a parting piece of advice, Chung paraphrases Abraham Lincoln's famed maxim and gives it a Silicon Valley twist:

"The best way to predict the future is to invent it, and technology's the best way to make it happen."

------

This piece is originally published on Breaking Hoops, a blog on innovators who redefine success. Sign up for the monthly newsletter here or like our Facebook page to stay up to date with our stories!