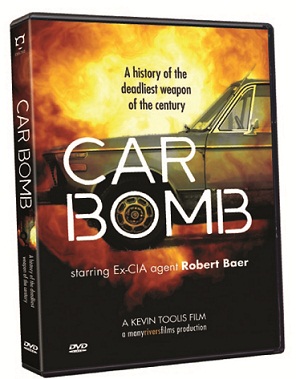

Robert Baer retired from the Central Intelligence Agency after 20 years in 1997, but he's still learning about security threats and about the region that was his specialty, the Middle East. In his current capacity as a journalist, Baer and director Kevin Toolis explore a potent threat to our safety that has been more devastating than nuclear weapons. In their new DVD documentary Car Bomb, Baer persuasively argues that vehicle bombs should hold the title of the deadliest weapon of the 20 century because they have been easy to make but can cause damage that's comparable to predator drones or landmines. Wars have been won and lost by them. They've been around since the infancy of the Automotive Century and, sadly, aren't going away. In the film, Baer goes around the globe talking with bomb makers who fought for Israel's independence, the Provisional  Irish Republican Army as well as various factions throughout the Middle East. He even talks with an American who went to jail for his attack and learned how to make the bomb from Encyclopedia Britannica! Having served in Lebanon in the 1980s when vehicle bombing was rampant, Baer certainly has a lot of first hand knowledge, but the most remarkable moments in Car Bomb come from when he gets the bombers to openly discuss why and how they did what they did. With his quiet, polite approach, he can get more useful information than Jack Bauer could with yelling and electrocutions. Baer doesn't think much of the histrionics of 24, but he's actually worked with Hollywood to try to get spycraft portrayed correctly. Syriana was based on Baer's book See No Evil, and George Clooney won an Oscar for playing an agent modeled on Baer. He's also been a recurring guest on The Colbert Report, using the show's comic approach to explain real-world intelligence issues. Contacted by me from his home in Los Angeles, Baer talked about what it's like to go from being part of the government to covering it as an outsider. Because of his vast experience, it was important to also get his perspective on the recent WikiLeaks dump of state department cables and other recent security issues. While Baer has been a worthy guardian of this nation's secrets, he's quite open about what he thinks is necessary to correct our foreign policy mistakes.

Irish Republican Army as well as various factions throughout the Middle East. He even talks with an American who went to jail for his attack and learned how to make the bomb from Encyclopedia Britannica! Having served in Lebanon in the 1980s when vehicle bombing was rampant, Baer certainly has a lot of first hand knowledge, but the most remarkable moments in Car Bomb come from when he gets the bombers to openly discuss why and how they did what they did. With his quiet, polite approach, he can get more useful information than Jack Bauer could with yelling and electrocutions. Baer doesn't think much of the histrionics of 24, but he's actually worked with Hollywood to try to get spycraft portrayed correctly. Syriana was based on Baer's book See No Evil, and George Clooney won an Oscar for playing an agent modeled on Baer. He's also been a recurring guest on The Colbert Report, using the show's comic approach to explain real-world intelligence issues. Contacted by me from his home in Los Angeles, Baer talked about what it's like to go from being part of the government to covering it as an outsider. Because of his vast experience, it was important to also get his perspective on the recent WikiLeaks dump of state department cables and other recent security issues. While Baer has been a worthy guardian of this nation's secrets, he's quite open about what he thinks is necessary to correct our foreign policy mistakes.

In the documentary, you said that you actually made some car bombs when you were working for the CIA. Yeah, they trained us on how to make these things, but more to show the destructiveness than anything else.

The aftermath of a Lebanese car bombing. ©2010 The Disinformation Company, LTD, used by permission.

What is it about car bombs that makes them more deadly than nukes? They're so easy to assemble. They're impossible to detect. Cars are omnipresent. You could just get them to any building in the world. It's not complicated. It truly is a poor man's air force. They're undefeatable as IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) are in Afghanistan. You just can't defeat them with technology. You can keep missiles from coming into the country with a missile shield, but you can't do anything about car bombs. Another aspect that's scary about them is if you invest hundreds or thousands of dollars in a car bomb, you can inflict billions in damage. They did this in London in the financial district. If you steal a car, it's even cheaper. You fill itwith nitrobenzene and a homemade detonator. It isn't just the billion you would cause in damage, like they did in London, but billions upon billions of money going to defeat these things.

Yes, because it would have cost more to keep an army in Northern Ireland that it would to make those bombs. There's no other way to get around with that much explosives except with a car or a truck. The amount of hypothetical damage you could do in a place like the United States is enormous. If you set off one or two of these things in a crowded area, then you'll have this country putting trillions of more dollars into security and then what happens to the Constitution? In the film, you've pointed out that the average American citizen can't just walk up to the Capitol any more. There's a blast wall between the parking lot and the Capitol now. Nuclear weapons are destructive, but they haven't been used for terrorism in any sense. In car bombs, they have. If you want to look at the problem of terrorism pragmatically, our biggest problem is the car bomb. Yes, because Faisal Shahzad, the would-be Times Square car bomber, was not a trained demolitions expert, thank God. Yeah, he was close. It's going to be a lot easier to make a car bomb than it would be to get explosives on an airplane. Eventually, we're going to come around and be able to find a way to be able to detect nitrates on clothes and whatever else. There's 20 basic elements that go into explosives. We'll eventually get into that technology and defend airplanes, which will leave the car bomb. There is a simple solution: Stop using cars. But that's only simple on the conceptual level. You can protect the post office or federal buildings, but they just shift targets. You get a civilian target. It's a potential nightmare in this country. One of the astonishing aspects of Car Bomb is that you were able to get a lot of people to talk on the record with you for this documentary. We got the Israelis. We got a lot of people to go on this thing. A lot of that has to do with the producers and the film company. Were you surprised that some of them were willing to talk? Now that you're no longer with the agency, you're a public figure, and anything they say to you could get out. Yeah, I think a lot of people have considered the car bomb an important part of their history. It changed the course of history in places like Israel. And certainly today with the way Palestinians and Israelis are divided, they felt the story should get out. You're fluent in Arabic and Farsi. Do you think you've got an edge over other journalists because you can actually speak these languages? I don't look at the subject clinically. None of this documentary was scripted. I just won't do a script. They sit down, and I say, "This is basically what I want to know." When you're interviewing suicide bombers or their networks, it's very important to speak their language. It's always a good icebreaker. It's always harder with a translator, if you don't trust the translator. You have to wait. They can think too long with their answers. I think it definitely helps, especially when the producer can't understand you and is cutting. He can say, "No, he gave this answer." I can deal with people in a chit-chat way. It's almost like you're gossiping with them. It was informal. If I reached an obstacle, I didn't press the question. I started asking other questions, and sometimes I got to get back to it. I noticed that you used that technique with the fellow who bombed the American facility in the 1970s. You didn't go in Mike Wallace-style or anything like that. You still got some pretty candid stuff. You just sit down and talk. There's no point in being accusatory. He did it. He went to jail for it. What I'm curious about is what was going through his mind. It reminded me of the column you wrote where you thought more of the torture memos should have been made public. In watching you talk with these folks, it's striking how your approach gets more useful information than if you had waterboarded them or been confrontational. There's this guy, Ali Soufan, the FBI agent who's been really articulate on this issue. He's just right. You get more out of talking to people. If you go in with questions you think you know the answers to, that's what happened with the waterboarding. They had all these analysts who were absolutely convinced that they had some very, very valuable Al Qaeda member in their hands, and they kept on waterboarding him them because they wouldn't give the answers they figured they had, and they just didn't. And it just turned into a fiasco. Because I'm a movie critic, I'm curious if you've seen the film Fair Game yet. No, is it good? I'm mixed on it, but it reminded me of when I read a column by William F. Buckley, Jr. where he criticized the outing of Plame. He said he had been an agent in Mexico, and somebody had outed him and he was lucky that none of his contacts had been exposed. It was one thing to out him, but anybody who came into contact with him was endangered. Is that accurate from your own experience? Yeah. Once you start to unravel these, it's very easy to lead to other identities for a government. If you've been assigned somewhere, and they realize what you're doing, they can go back and check cell phone numbers, meetings, surveillance and all this. It makes it considerably easier for a hostile intelligence service to find somebody. How does it feel to be a journalist after working as an agent? If I write about the CIA, I'm obligated to show them my opinion pieces or anything about my time in the CIA. What I argue about with them is they say your thoughts about current events are classified. I find that very odd. I don't pay much attention to them. Like the bombing at Khost (the Afghan city where seven agents were killed on December 30, 2009), they wanted to suppress that article (in GQ). I figure now that anything that I do is a journalist, that if I identify a source, where I learned something from someone else, it puts me in a different light. It puts me in a different category of people. Many ex CIA agents are writing about their own careers. Buckley did. There's a lot of people who did that. In the research that you and Mr. Toolis did for the documentary, were you surprised that car bombs went all the way back to 1920? I had no idea the first one was done on Wall Street. A lot of the back filling of the historical information I find fascinating. There are so many things I never paid attention to. I never paid any attention to the Israeli car bombs. I never paid any attention to the mob car bombs. It adds to my education.

Baer with gunmen in El Hinweh camp, south Lebanon. ©2010 The Disinformation Company, LTD, used by permission.

Even though you were in Lebanon during the 1980s when this stuff was happening, there still more to learn, obviously.

I think it's amazing. We're going into prisons and meeting suicide bombers. It's an education you'd never get in the CIA. It's very much a complement doing journalism. There's also the fact that you're going through open sources. You're always referring to them. You don't do that in the CIA. You were laser-focused on one problem, on one person. You don't have time to go back and conceptualize and put it in historical context. I look at this journalism stuff as just a continuation of an incomplete education. In the recent Financial Times column you wrote, you said that this latest WikiLeaks dump of State Department cables was potentially devastating because many negotiations can only be done through back channels. They can't be conducted through conventional diplomacy. You said that it was essential in dealing with leaders who don't operate the way western leaders do. You have to look at the point of view of the State Department. They are like a good journalist. They need to protect their sources. The New York Times is not putting its sources on the Net. If they want to talk about openness, why don't they talk about their sources, their informants, their Deep Throats, and the rest of them? Because they know better. It undermines their credibility. It ruins them as a newspaper. It's the same with the state department. Someone says, "Look at how cynical the diplomats are." Well, no shit. Are we just discovering that? Diplomacy has always been like that, going back to Rome and before.

On the other hand, I love reading the stuff on WikiLeaks about the fact that the Chinese know so little about North Korea. I find that illuminating because when I was in the CIA, the Chinese weren't talking about North Korea at all. And they're sort of guessing what is happening in Pyongyang. As a journalist, I find that absolutely fascinating, or King Abdullah complaining about Iran. It's completely useful. On the other hand, if I had my other hat on and I were a diplomat, you know, the next ambassador to Germany -- what German is going to talk to our ambassador or political counselor about the internal workings of the government? This guy (Helmut Metzner, an aide to German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle) just lost his job today (for providing information to the U.S. embassy).

And this guy (Dmitry) Firtosh (a natural gas tycoon) in Ukraine, we always sort of knew he was dealing with the mob, but, in fact he went to the American embassy and told the ambassador. The message to Ukrainians is don't ever go into the American embassy ever again. What this all leads to is this intellectual isolation. Because now if the only thing we know about the world is what we read on the CNN site, then we as diplomats are really lost. I haven't seen a lot of this on the net, but the people who deal with the human rights groups are an invaluable source of information on totalitarian governments because they can put you in the picture right away. But now, they've been exposed. The Pentagon Papers made perfect sense to me because it was internal deliberations about getting into Vietnam. It just showed the hypocrisy of the government and the internal debate. It doesn't really damage are national security. I think it helps your national security because we now appear to be an open society.

I don't have any problems with James Risen's story on warrantless wiretaps because that's not sources and methods. It's purely a legal issue. The White House is bypassing FISA (Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act) warrants, which is a matter of illegality. It doesn't mean listening to more phones or fewer phones. It doesn't mean anything in terms of the opposition. It's just that they were cutting corners on the law. I think that that's a righteous leak. But if you start naming sources, or you start getting into the National Security Agency or the codes for nuclear bombs, you get into all sorts of problems. It's like leaking a police investigation, where you're putting out in the news how far the police are. The criminals can change course. In one of your columns, you pointed out that some of the data in the leaks is garbage. In one memo you cited, Osama Bin Laden was having a weekly public meeting in Pakistan, which is just about impossible. That was total bullshit. What scares me is that was the military's stuff (instead of the CIA's). That anyone would put that on paper I find that astounding, or that Mullah Omar was deciding where to put bombs. I found that stuff fascinating because it confirmed my suspicion that the level of our intelligence in Afghanistan is pretty poor. He's not anywhere driving out in the open. He's very much caught up in a cave, or dead, or in some government compound, or whatever. But he's not going to meetings about placing IEDs. It's just not happening. I would like to say that I should be the one who decides what goes out in public or what's dangerous, or you, or Tom Friedman, or somebody else. The problem the governments faces is that you can't let private citizens decide what's classified and what's not.

What you really need in all of this is an effective Congress that will simply look at a problem, a scandal, and will look at our foreign policy, write a report, have it cleared with the right agency and have it reach the public that way. And then meet out punishments or recommendations to remove people. Or you have to have effective IGs (Inspector Generals) or ombudsmen to deal with this stuff. You really have to get a competent Congress, and we don't have one. It's very much a dilemma. I would very much like to see internal memos from Goldman Sachs made public. I think that affects Americans more than what we're doing in Germany or Chechnya or all these other cables that have come out. I'd like to know precisely how cynical was Goldman Sachs during the financial crisis and leading up to it. I go back and forth on freedom of the press. There is a nice balance somewhere there, but on the cynicism of these exchanges and why don't Americans do this sort of stuff, all I can say is that this stuff really hurt the State Department or any government official who works overseas. It's already harder to get someone to meet you as an American.

Ultimately WikiLeaks is going to help academia and help us understand where we're coming from. And if you look at the stuff intelligently, with the stuff about the Saudis funding Al Qaeda, did you see a name in there? Diplomats are working on rumor, too, just like everybody else. That gave me an uneasy feeling. You could misuse that. "Well, maybe there are a couple of Saudis funding Al Qaeda." Is it a lot? Does it matter? I think more money is coming into Al Qaeda from fuel contracts in Pakistan than from Saudi Arabia, but we've just decided to ignore that. Every truck that goes across (the border) gives thousands of dollars to the Taliban and maybe Al Qaeda. I don't know. We're essentially paying for both sides of the war. Congress has said this. But it's like amnesia. Everyone's focused on this one cable, which may be wrong. The state department, they're living behind fortresses, too. I've read portions of your book, Sleeping with the Devil: How Washington Sold Our Soul for Saudi Crude. You wrote that before King Abdullah assumed the throne in Saudi Arabia. How have things changed since you wrote the book in 2003?

His arrival has been like night and day. The Atlantic did a cover piece on that book. I didn't really like it because it made a prediction, and predicting anything in the Middle East is bad.

Two things happened: You've got King Abdullah, and he's very good. And he's got Muhammad bin Nayef, son of the interior minister (his official title is assistant interior minister for security affairs). The two of them have really turned Saudi Arabia around. The other thing that has turned things around is the price of oil. They have all the money in the world to pay off commissions, payoff tribes that had been unhappy when the price of oil was $10.00 a barrel. The Saudis have bought themselves time. In both Sleeping with the Devil and Car Bomb, you point out that the petroleum dependency is a major security issue.

I still think it is. The fact is if you look at WikiLeaks and the comments on the king of Bahrain, the Crown Prince of Kuwait and with King Abdullah. From what has come down to us, the security situation is not happy in the Gulf. They truly look at Iran as a menace. I wrote a book about this, but nobody paid attention. I'm not saying (Iran) is a menace, but they look at it as a menace. And that's much more important because it keeps the gulf Arabs on the brink with some kind of conflict with Iran, either in Iraq or Lebanon or just in the Gulf itself. The fact is it sits on the world's oil reserves. It's just there. If you get that and a tight oil market -- $500 a barrel for oil? It's possible. Who knows? Here's the thing, if you look at things pessimistically, you always sound smarter. If you go around saying the world's going to be fine, they look at you and say, "That guy's an idiot." It's a good built-in mechanism.