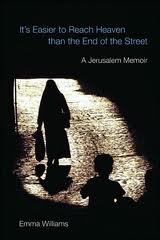

It's Easier to Reach Heaven than the End of the Street: A Jerusalem Memoir

By: Emma Williams

Bloomsbury, ©2006 (UK), Olive Branch Press, ©2010 (USA)

"Everyone talks about it. The 'situation.'" That, Emma Williams explains, is how both Israelis and Palestinians refer to the 60-plus years of violence that has ensued since the unilateral declaration of the Jewish state, and the ongoing displacement and occupation of the Palestinian people.

In her extraordinary first book, It's Easier to Reach Heaven Than the End of the Street: A Jerusalem Memoir, Williams manages to capture the human suffering on both sides of this conflict by living in the "situation" and not ignoring its frightening circular impact on the parties. Her honest accounts of the impact of suicide bombings on Israeli society juxtaposed with Israel's nonstop pounding of Palestinians under occupation leaves you breathlessly grappling with the sheer magnitude of this pointless violence.

Israelis and Palestinians have both fallen victim to what seems to be a spiraling destruction of themselves. "We were happy. It was just the situation, living alongside two extraordinary peoples who were bent on killing each other. Except," says Williams, "they weren't all. The killing was being driven by the few."

Williams, an Oxford-educated medical doctor, wife and mother of four, begins her story as she moves to Jerusalem with her husband Andrew Gilmour, a United Nations official, in the summer of 2000. Peace still seemed a distinct possibility, says Williams, until "on 28 September, Ariel Sharon came marching in" on the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif, and triggered what is now known as the second Palestinian "Intifada" or uprising. Sharon himself rejected the notion that his visit was the provocation that set Palestinian passions aflame, but Williams points out: "You can believe what you like of the legends and whispers and mysteries, but you cannot underestimate the significance of the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif for millions of Jews and hundreds of millions of Muslims."

Williams goes on to explain that Sharon's true goal was to provoke an end to the Camp David accords and Oslo peace agreement -- an affront to both the Palestinians negotiating in good faith, and the Israeli opposition Labor party, who now looked like they were negotiating with nothing more than a thuggish counterpart.

But such was the nature of the Ariel-Sharon-driven Second Intifada, that Israelis were denied a clear picture of the people they occupied. Says Williams: "IDF officers sometimes confided that they dreaded a well-coordinated mass campaign of non-violence above any form of resistance: Palestinians were not supposed to look moderate, reasonable."

Instead, the indoctrination was relentless. Living as a Westerner in Jerusalem, Williams noticed that Israelis "no longer saw them (Palestinians) -- literally and figuratively." When IDF combat units blasted through walls of homes "searching, arresting, looting, beating, and blasting out again to do the same to the next family... we were told that 'terrorist nests' were being rooted out."

Each page reveals unacceptable injustices toward Palestinians, the pain of the Israelis -- and yet the asymmetry in this conflict is startling. Israelis seem utterly clueless about the havoc their occupation wreaks, and then shocked when the violence spins their way.

Shortly after Emma's arrival in Jerusalem, Palestinian resistance groups started a massive campaign of suicide bombings in Israel in retaliation for the assassinations of their leaders, many of them moderates. As one Israeli mother tells Williams: "Look what happens every time we assassinate one of their leaders -- more violence, more suicide bombings." She blames a handful of Jews diaspora for pushing Israelis "to hit them (Palestinians) harder and harder 'until they learn.' 'You must do this,' they rant from far away, 'whatever the costs.'" But the costs, she says "are the lives of my children."

Per chance, I was in Jerusalem directly before the second Palestinian intifada. I can remember palpably feeling the tension between Israelis and Palestinians. Although most residents at the time felt a breakthrough toward the establishment of a two-state solution was still possible, my observations told me otherwise. Settlements continued. Young Jewish men, newly emigrated from America, sat on chairs in front of Palestinian homes trying to intimidate the owners. The soon to be Prime Minister Sharon's home was firmly wedged in the middle of Arab East Jerusalem, in defiance of the very concept of ending the occupation and exchanging land for peace.

Most startling was the project in West Jerusalem near the Wailing Wall. The Israeli government spent days expanding the wall under scores of Palestinian houses that were directly above. You could see the floorboards of their homes as you walked through the tunnel of expansion. As Williams notes consistently through the book, "What could they do?" In my opinion, the situation was clearly counterintuitive to peace. Just weeks before Prime Minister Sharon's provocations, I recall telling an Israeli friend the situation was about to blow. A few days later it did.

And the peacemaking politics were not much better. As a backdrop to her story, Williams describes an increasingly intransigent Israeli negotiating position trying to wrangle out of commitments to UN resolutions, while their partners on the other side -- the fresh-from-exile "Tunis Crowd," possibly the worst negotiators the Mideast has ever seen -- jockeyed for mere crumbs.

It is hard for many of us to imagine living in a land that is so clearly divided between peoples. The strain of occupation, roadblocks, and military containment gave birth to reprisals that cast an entire population as "terrorists" and people who don't value life. But death, horror and destruction don't recognize nationality or religion. War happening all around, land confiscations, no access to food, deliberate electricity and water deprivation, and young, sick children and birthing mothers denied healthcare because the Israeli Defense Forces won't permit them to travel to hospitals. People continuing to be displaced. The reality is that the endless violence preys on everyone -- the old and the young, the healthy and the sick, and the men and women, the Palestinian and the Israeli, the occupier and the occupied; all of whom are simply trying to get on.

Williams captures it all through her own experiences living on both sides of that fence. She describes her frustration waiting in line at "yet another checkpoint" to get to her job in the West Bank or to drive her Palestinian nanny home. And she should know. This brave, crazy Englishwoman gave birth to her fourth child in the midst of the Intifada -- in a Bethlehem hospital still under siege by Israeli soldiers.

At one point, I truly had to close the book and walk away from it for a while; the reality of people's lives became so frightening. Williams on her way to a prenatal checkup is, as always, forced to go through a checkpoint in Bethlehem, a Palestinian town under containment by the IDF. In the queue, she watched the young Russian immigrants who were now Israeli soldiers allowing or denying the sick access to the only hospital, and the elderly denied the right to go to their places of worship to pray.

Directly ahead of Williams was a Palestinian woman, also noticeably pregnant, trying to pass through the checkpoint in order to see a doctor: "She offered her papers and her appointment card... Dennis [the soldier] was unmoved, and motioned with one circling finger for her to turn around. She complied, wordless." There was no logic, no reason. Williams asked why the soldiers had refused to let the woman through: "Challenged, he looked mildly embarrassed. 'How do I know she's pregnant?' he said, bolstering himself. 'Everyone's fat around here.'"

The irony of the checkpoints, Williams notes, is that "this was not about security. Even the IDF said checkpoints didn't work." The real reason, she says, is that checkpoints "close down lives: waiting, each car, long enough to be searched and then not searched, just made to wait, to gnaw with frustration day after day, twice a day."

The doctor knows she can walk away from it and return to England or New York. But Palestinians will have to continue to endure. Williams left Jerusalem in 2006, and the "situation" continues to spiral downward. "Is it too much to hope that the situation will be addressed at last?" she asks.

If you read one book on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, read this one. You get a good dose of the politics and history of the past and present, but woven through it all is the humanity of both Palestinians and Israelis, through the eyes of an exceptionally gifted observer. In the end, Williams is right on target when she says:

As long as it remains easier to reach heaven than the end of the street -- or field, or school or hospital or the next-door village, let alone Jerusalem, the City of God -- then no security measure yet devised will stop people seeking a gruesome short cut to end their hell on earth.