Last month, when a neo-Confederate gunman opened fire in Charleston, South Carolina, in a historic black church with roots in slave uprising, in the city where the Civil War began, the tragedy was so steeped in history it seemed we could no longer avoid looking hard at the long legacy of slavery in our nation's past.

And yet still we hesitate. Mere hours after the murders at Emmanuel AME Church, South Carolina Representative Mark Sanford attempted to sweep the thing-of-which-we-do-not-speak under the rug. "We come from a strained past based on slavery existing in our state," Sanford told CNN, "and that's a regretful past. But ultimately, past is past." Slavery happened a long time ago. The past is past. Nothing to see here, folks.

Yet every year on Independence Day, we celebrate the fact that the past is not past, coming together as a nation to celebrate the past, to revere the past, to honor the collective ideals upon which our nation was founded. We pay tribute to the ideals of freedom and liberty and remember that "all men are created equal."

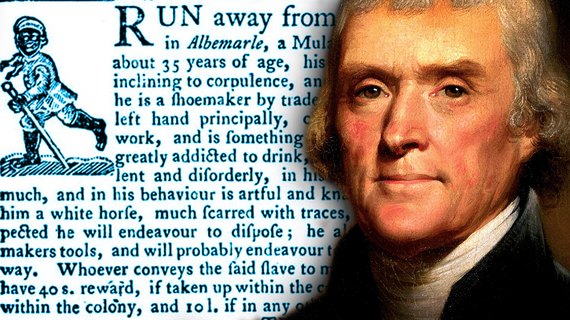

Recent events are an all too brutal reminder that we are still remembering a partial past, a selective past. There is no room for the "strained past" of slavery in the story of our nation's founding as we currently tell it. We well know that at the time the Declaration of Independence was written, all men were not created equal - roughly twenty percent of America's population in 1776 was enslaved. Too often we set this uncomfortable history aside when we celebrate our nation's founding. We can no longer afford such historical amnesia. We must take slavery seriously as part of our national origin story, not simply because it existed, but because it is intrinsically bound up with who we are and who we claim to be.

One important place to look for the connections between slavery and independence is in the efforts of those who were not free to join in on the rights and privileges of the founding generation. Consider the story of Sam Howell. In 1766, as the American colonies were just beginning to stir in opposition to British policy, Howell ran away from his master and headed to Williamsburg, Virginia. Howell had been unfree since the day he was born. He had inherited his status from his mother, herself a servant of mixed-race ancestry whose grandmother was the child of a white woman and a black man. Although Virginia law bound Howell to his master until the end of his term, he believed he was wrongfully held and claimed that he had a right to his freedom. He headed to Williamsburg to find himself a lawyer who would defend his right to liberty.

Howell found a young lawyer named Thomas Jefferson to take his case. At the time, Jefferson was relatively new to the practice of law and the youngest lawyer in Virginia's elite bar. Because of Howell's unfree status, Jefferson took the case pro bono. When he agreed to represent Howell, Jefferson probably knew it would be a long shot. By the time Howell approached Jefferson, he had already sued once for his freedom in the county courts and lost. As well, he had appealed to the King's Attorney in Virginia, but was ordered to return home to his master. Undaunted, Howell sought out Jefferson's services as a last resort. To make matters worse, the attorney for the defense was Jefferson's former mentor, George Wythe, an established attorney and one of Virginia's great legal minds. It would be a tough case.

Nonetheless, Jefferson crafted a finely tuned set of legal arguments in defense of Howell's right to freedom. The most compelling of these was a radical argument about natural rights. When the case of Howell v. Netherland came before the court in 1770, Jefferson argued that Howell should be set free because all men possessed a natural right to freedom and liberty. He explained that "Under the law of nature, all men are born free, every one comes into the world with a right to his own person, which includes the liberty of moving and using it at his own will. This is what is called personal liberty, and is given him by the author of nature." In 1770, the Virginia courts were neither swayed nor particularly interested in hearing Jefferson's sweeping appeal to abstract notions of freedom. They decided against Howell and denied him his freedom.

Jefferson may have lost his case, but not without leaving a legacy. His argument in Howell's case was the first time that he had expressed such ideas openly. In many ways, Jefferson's argument on behalf of Howell was a "rough draft" of sentiments he would express more eloquently when the colonies declared their independence from the British. Just a few years after he represented Howell in court, the Continental Congress asked Jefferson to draft a declaration of independence from the British Empire. In writing this declaration, Jefferson transformed the clunky language of natural rights that he had recently used on behalf of Howell and turned them into a lyrical and powerful statement of universal liberty and equality. On the eve of the American Revolution, echoes of Howell's freedom suit resonated through Jefferson's powerful words: "All men are created equal, endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness."

It is these words that form Jefferson's most lasting legacy. It is these words that we largely credit to Jefferson and celebrate every year on July 4th. But lurking in their shadow is the equally important and generally overlooked figure of Sam Howell. He has been there all along, hiding in plain sight, waiting for us to remember his historical legacy and the tangled, inescapable connections between human bondage and America's founding ideology.

It has been all too easy for Americans to celebrate Jefferson's words without considering those connections. Doing so allows us to sever our nation's founding from the ignominy of slavery, to insulate ourselves from the painful memories of racial oppression and human exploitation. But doing so has consequences. However deeply we try to repress the memory of slavery in our national narrative, it remains a raw nerve in the present, as the blood spilled in Charleston has all-too painfully reminded us. To face an honest history of our national origins, we cannot celebrate the land of the free without acknowledging the presence and struggle of the unfree.