Glenn Ligon, Rückenfigur, 2009. Collection Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Glenn Ligon.

The Whitney Museum of American Art's new home opens to the public on May 1. Installed at the lower end of the Highline in the Meatpacking District, overlooking the Hudson River, the Renzo Piano-designed building nearly doubles the Whitney's exhibition space, and introduces a public plaza, numerous outdoor terraces and a theater. The expansion provides much-needed legroom for a collection that's grown more than ten times since 1970, the year the museum first settled into its former, Marcel Breuer-designed accommodations on Madison Avenue.

View facing the Hudson River. Photograph by Karin Jobst, 2014.

The Whitney's spacious new digs allows for the collection to stretch out and flex with "America Is Hard to See," an ambitious exhibition that aims to reevaluate the history of American art from 1900 to 2015, presenting more than 600 works of art, many of them rarely exhibited prior, by over 400 artists. The stalwarts of the canon are presented alongside artists whose oeuvres have been reassessed and revived, filling in the gaps of our understanding of art history. The title, drawn from a Robert Frost poem, "points to the impossibility of offering a tidy picture of this country, its culture and, by extension, its art," offers Chief Curator Donna De Salvo, who organized the exhibition around a series of 23 "thematic chapters that together reflect on American art history from the vantage point of today."

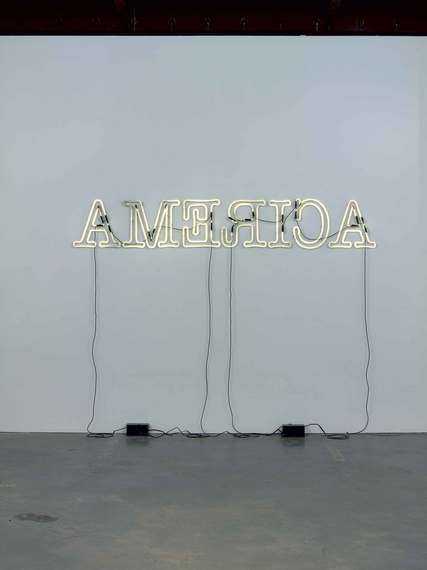

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, "Untitled" (America), 1994. Photograph © Timothy Schenck, 2015.

What the exhibition offers is an unprecedented view of the scope, and omissions, of the Whitney's collection. While it skews predictably toward a New York-centric perspective, it succeeds in many ways by introducing the works of lesser-known or hitherto marginalized artists alongside canonical classics. Nestled among the Whitney's outstanding icons -- works like Jay DeFeo's The Rose (1958-66) and Mike Kelley's More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and the Wages of Sin (1987) -- and art history's usual suspects -- your Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock -- one will find some welcome surprises within the institutional narrative of the collection, from the noticeable emphasis on works by women artists, to the refreshing mix of new media, particularly film and video works, that have been inserted among the paintings and sculptures. The exhibition begins in the first floor lobby and public plaza area with a gathering of works focusing on the museum's roots and the life and artistic milieu of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. The exhibition then proceeds chronologically through the Whitney collection, from the eighth floor galleries down to the fifth, with Richard Artschwager-designed elevators bringing visitors up, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres's light-string installation Untitled (America) (1994) elegantly guiding them down the stairwell. The third floor of the museum is occupied by an education center and a 170-seat theater, which augments the inaugural exhibition with a screening series of seventeen film and video programs drawn from the Whitney collection.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918. Collection Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. ©2014 Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The Whitney's fresh re-reading of art history is most pronounced on the floors dedicated to modern art, pre-1975, where the inclusion of lesser-known artists makes a striking impact. On the eighth floor, early abstraction influenced by the European avant-garde meets the American landscape. An evocatively abstract painting by Georgia O'Keeffe, with gentle organic forms in pink and white and blue, finds a surreal twin in a visionary landscape with a solitary swan, painted by her contemporary Agnes Pelton. Other traditions mix together one floor below, where the sublime grandeur of the West is rendered in all its aspects: in a serene sunset by Edward Hopper, a moonrise by Ansel Adams, and a series of woodblock prints of Yosemite National Park by the Japanese-American artist Chiura Obata from the 1930s.

Chiura Obata, Evening Glow of Yosemite Fall, 1930. Collection Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Gyo Obata.

The chapter on Abstract Expressionism -- the art movement that in many ways epitomized the art of the United States -- opens with an airbrush and enamel on canvas abstraction by the sole female founding member of the New York School, Hedda Sterne. It continues with paintings by Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and others in an impressive display of gesture among sculptural counterparts by John Chamberlain and Mark di Suvero. A remarkable section of experimental abstract films made between the 1930s and 50s, from Mary Ellen Bute, Len Lye and Robert Breer introduces an exciting and underexplored area of crossover between media. Political paintings by Jacob Lawrence and prints by Hugo Gellert complicate the narrative of abstraction, as does Raphael Montañez Ortiz's Cowboy and "Indian" Film (1957-58). Ortiz's film, recently acquired by the Whitney, splices together scenes from Hollywood Westerns with a World War II newsreel, and dramatically prefigures the art to come in the next decades, with its deconstruction of mass media images and cultural stereotypes.

America Is Hard to See, installation view, 2015. Photograph © Nic Lehoux.

Ortiz's work reappears on the next floor, with a radical assemblage of wood, steel, rope, fabric and horsehair. This chapter of the exhibition is befittingly titled after the little known work by the dazzling and notorious underground filmmaker Jack Smith, Scotch Tape (1959-62), and features, along with the Ortiz, works by Bruce Conner, Robert Rauschenberg and others, demonstrating tendencies toward accident and the abject in works from the 1960s onward. Smith's film celebrated such accidents -- so named for the piece of tape that had become inadvertently lodged in the corner of the camera, unnoticed while Smith filmed a group of boisterous dancers, writhing through a scene of destroyed concrete and rebar.

America Is Hard to See, installation view, 2015. Photograph © Nic Lehoux.

On the same floor, Minimalism is revitalized by the works of artists like Carmen Herrera and Jo Baer, and Pop Art by Yayoi Kusama and Marisol. Spare white canvases by Herrera and Baer sing pitch perfect among Ellsworth Kelly's white painted aluminum sculpture, Jasper Johns' White Target (1957) and monochromes by Frank Stella and Ad Reinhardt. The exhibition's treatment of Pop Art and its aftermath benefits from the inclusion of Chicago Imagists like Jim Nutt and the bondage-tinged works of Nancy Grossman and Christina Ramberg feel absolutely revelatory together. Peter Saul's massive, lurid Saigon (1967) writhes on the wall, drawing all eyes to its comic grotesque.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #45, 1979. Collection Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Cindy Sherman; courtesy artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

The fifth floor brings us into the contemporary art age (1965 to today), with an astonishing array of contemporary works. It is a bit of a hodgepodge, reminding of Whitney Biennials past, with a bit of everything from Cindy Sherman's Film Stills to Cory Arcangel's Super Mario Clouds (2005). The narrative here is heterodox, evolving and exciting. Much like the collection of the Whitney. There are gaps -- many have noted the absence of Latin-American and Native American voices, the spotty representation of art from the West Coast and Midwest, and the lack of outsider art, craft and design -- but these lacunae can (and should) be corrected through collecting. Many of the works by the more unfamiliar artists mentioned above were acquired by the Whitney decades after the artists made them -- the gaps in art history, after all, are much easier to locate in retrospect. And with its new building, the Whitney's collection has even more room to grow.

The new Whitney Museum. Photograph © Nic Lehoux.

--Natalie Hegert