Only in the pampered, plush 1870s, could a lawyer even dream of explaining why a client shot his father to death by arguing that the young man was not accustomed to rising so early in the morning. The defendant's father's unexpected presence at the Sturtevant House in Manhattan, where the young man was staying, shortly after 6 AM, disturbed his peace of mind and allegedly provoked him to parricide.

Only in the pampered, plush 1870s, could a lawyer even dream of explaining why a client shot his father to death by arguing that the young man was not accustomed to rising so early in the morning. The defendant's father's unexpected presence at the Sturtevant House in Manhattan, where the young man was staying, shortly after 6 AM, disturbed his peace of mind and allegedly provoked him to parricide.

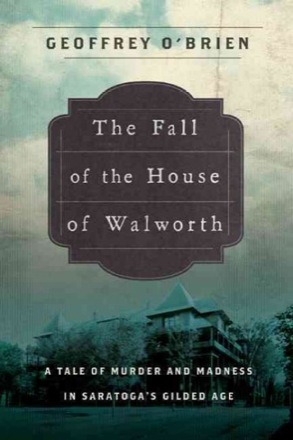

That is just one of the preposterous claims emanating from the fascinating Walworth murder case, nimbly retailed in Geoffrey O'Brien's new book The Fall of the House of Walworth: A Tale of Madness and Murder in Gilded Age America. At the height of what Edith Wharton dubbed "The Age of Innocence," America was entering an era of exhilarating growth after the Civil War, and unprecedented wealth. A new leisure class had quickly sprung up that mimicked British aristocracy, but with a decidedly wacky American bent. The murder of popular author Mansfield Walworth (Warwick, Lulu, Beverly) by his handsome, sophisticated son Frank took place in 1873, the same year the excessively frothy expansion turned into a widespread panic. America was dancing on the edge of hysteria and the Walworth parricide, and its ensuing media frenzy, seemed to encapsulate all the neurotic obsessions of the times.

How Frank Walworth came to fire four bullets into his father is the crux of O'Brien's book, but not necessarily its thrust. O'Brien uses the murder as a springboard to dive into larger questions of America's social legacy, in particular the rise of Saratoga Springs as one of the country's preeminent resorts of the rich and famous. In doing so, he unveils with almost Poe-like intensity the decline of the Walworth dynasty, which had become a prominent presence in that moneyed, horsey playground.

The book opens with a haunting Gothic scene: 65-year-old spinster, Clara Walworth, daughter of Frank, walks through her rambling, dilapidated mansion, "a space thick with ghosts," revisiting painful memories. She's an American Miss Havisham, the last of a line, the tail end of a distinguished family that at one time had reached the pinnacles of achievement only to fall into darkness and despair.

From there O'Brien chronicles the remarkable rise of Chancellor Reuben Hyde Walworth, the family patriarch, who had fought with honor in the War of 1812. Two decades later, after a stint in Plattsburgh, he settled in Saratoga, at "Pine Grove," with his wife Maria and five children.

The youngest child was Mansfield, a "little rascal" who proceeded to manifest the worst of American vices. As if in some ancient Greek tragedy, Mansfield ended up marrying the daughter of his father's second wife. After Maria's death, the Chancellor had formed a union with a well-connected Southern belle, Sarah Hardin, a relative of Mary Todd Lincoln. Her daughter Ellen wed Mansfield, apparently with the blessing of all parties involved. It was a star-crossed merger that led to even deeper miseries for all concerned.

Mansfield proved to be reckless, bombastic and a violent drunk. He was imprisoned briefly, most likely erroneously, in the Civil War as a spy for the Confederacy. After the war, he took up writing, penning a series of overheated novels that appealed to middle class readers primed on penny dreadfuls. Although almost universally panned by critics, his books did fly off the shelves and he fancied himself a "litterateur" of the first standing.

He was also two-timing his wife with a mistress, while sending threatening letters to Ellen, warning that he would kill her if she didn't send him the money he needed. These foul-mouthed letters, some of which Ellen had shared with her devoted and highly sensitive son Frank, would later prove helpful in the 19-year-old's defense.

O'Brien is at his best in describing the trial, and its aftermath, and in capturing the personalities of the lawyers, on either side. The elevated language used by both parties is engrossing, as well as the reasoned analysis of the presiding judge. Even though it was inevitable that Frank would be found guilty (he had immediately turned himself in and confessed), impassioned arguments were made that he was suffering from epilepsy and "inherited insanity." The jury opted for murder in the second degree, which carried a life sentence.

Within three years, however, after stays in Sing Sing and Auburn, NY, Frank was pardoned by the governor. All traces of insanity and epilepsy vanished after his release and he went on to become a champion archer. Sadly, however, he died less than ten years later, leaving behind his wife, and only child, Clara, the eccentric spinster figure of the opening chapter. Frank's brother Tracy would end up having mental problems himself and eventually took his own life by hacking away at his neck (on both sides) with a knife. The other siblings led equally frustrated lives.

Their mother Ellen, ultimately, turns out to be the main subject of this exhaustively researched and well-written book. She is an enigmatic figure. On one hand her implacable resiliency in the face of repeated disasters is uncanny. And yet, her cold, aloof perfectionism makes her less than an appealing heroine. For it was she who inspired Mansfield's venomous tirades, and who, she herself admitted, may have provoked her son into committing his unfathomable crime. Ellen went on to become a fixture of Saratoga society (she'd already turned Pine Grove into a successful boarding school, the Walworth Academy) and devoted her life to various causes, championing landmarks for the Battle of Saratoga and helping to found the Daughters of the American Revolution. She could be construed as a symbol of America herself, representing its hardy virtues and unbending flaws.

If one must find any fault in O'Brien's opus, it is only that he does not fully bring to life Frank Walworth, the main actor on this tragic stage. But then Frank may have been a cipher, an empty shell despite his good looks and athletic prowess. His poetry, which O'Brien quotes readily, falls flat on the page and exudes a superficial sentimentality typical of the era. He was after all his father's son.