I work for the Wildlife Conservation Society because I believe that each generation must safeguard our planet's wildlife and natural resources for future generations. When wildlife populations are threatened by human behavior, balancing present and future needs implies restricting to some extent our current use of wildlife and habitat.

Before joining WCS I worked for over two decades with hunter-gatherers and forager-farmers in Central Africa and Latin America, and during my time at WCS, I have worked closely with many of these communities in WCS programs. During this time I saw firsthand how these most geographically isolated and politically marginalized people on the planet were almost completely dependent on wildlife as a source of nutritional protein.

Local men and women in northern Congo benefit from their wildlife by working as tourist guides. (Photo © WCS)

When a national government decides to allocate their lands to logging, mining or agricultural concessions, the local people living there are typically neither consulted nor compensated. This also used to be true when protected areas were created, and it sometimes still is. So though I am a strong advocate for creating protected areas to conserve wildlife, I also believe that the cost of conservation of globally important public goods should not unjustly fall on those least able to bear them.

For most of human history, local interests tended to dominate those of the larger society when it came to laying claim to and protecting natural resources at risk of being depleted. The establishment of Yellowstone, the planet's first national park, in 1872 shifted the balance in the opposite direction. Today, one might argue that the interests of commodity companies are steamrolling both local and societal interests in decisions about how land and resources are used.

Who wins and who loses when land and resources are taken to establish industrial concessions, infrastructure, or even protected areas depends on why the expropriation was deemed necessary and who agreed to it. In representative democracies with clear property rights and rule of law, adjudication of claims is either negotiated through public debate and the ballet box or litigated in court.

In Indonesia the local Sasak fishing community benefits from setting and enforcing their own awig-awig fisheries management system. (Photo © WCS)

In places without these institutional safeguards, winners and losers are autocratically mandated, and losers have little if any recourse--an injustice that lies at the core of the debate about the legitimacy and desirability of the taking of land for economic development.

By securing formal recognition of indigenous peoples' rights and access to natural resources within their territory, conservation groups can help prevent such expropriation. WCS has done this with the Takana and Isoseños of Bolivia; the Ticuna, Cambeba, Cocama and caboclo peoples of Mamirauá, Brazil; the Huaorani of Ecuador; and the Cree and Ojibway of northern Ontario.

Nevertheless, without public input into decision making, many local people will continue to risk being physically displaced or denied access to traditional resources by the establishment of parks and reserves.

Inuit community members talk about how to protect a walrus haul-out close to their village. (Photo © WCS)

To take just one example, setting up a no-take zone to protect and restore reef fish productivity has been shown to be a huge benefit to fishers but will likely result in reduced catches initially. For both ethical and practical reasons, some form of financial or technical assistance should be provided to help families that have lost access to a key local resource from sinking into poverty.

When property rights are ill-defined or vested solely in the state, taking of property and rights is often unjust and uncompensated. It also conflicts with Article 17(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948, which states that "no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property."

The conservation community is doing better in seeking public consensus on when the taking of property or rights to establish or maintain a protected area is or is not desirable, legitimate, or ethical. And we are beginning to take a more visible stance on when such action does or does not warrant compensation. We still need to do a better job in helping ensure that rights holders are able to equitably participate in these land and resource discussions and decisions.

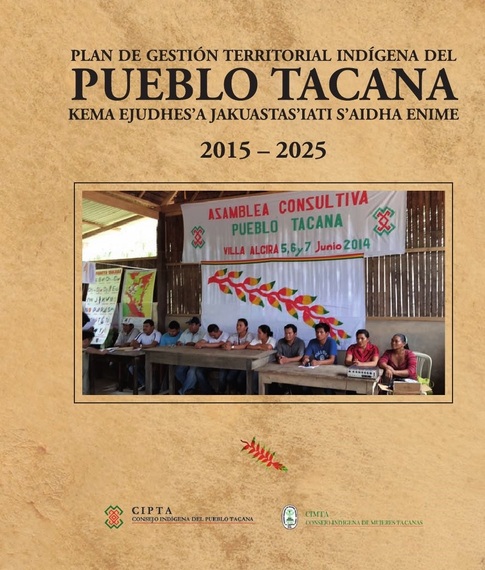

In Bolivia the Tacana indigenous people developed a new 10-year plan to sustainably manage their legally recognized territory. (Photo © WCS)

Building and maintaining a strong constituency for protected areas across all levels of governance is essential if wildlife and wild places are going to be conserved long into the future. This requires honesty when considering the benefits and costs of protected areas, an inclusive approach to decision making, and a willingness by those who benefit from the taking of natural resources to compensate those whose lives are diminished in the process.