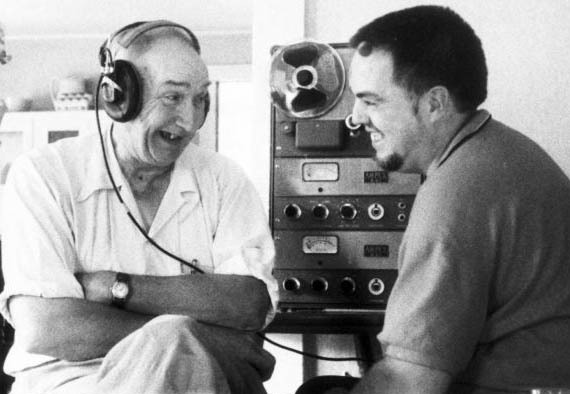

Wade Ward listening to playback with Alan Lomax at the Ward home in Galax, Virginia, August 31, 1959. Photo by Shirley Collins. AFC Alan Lomax Collection. Used by Permission.

As I've mentioned before, 2015 is the centennial year of the great folklorist Alan Lomax. The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, the Association for Cultural Equity, and other organizations are celebrating with a variety of programming incorporating archival work, online presentations, conference appearances (including SXSW!), lectures, symposia, and public performances of the great music Lomax collected.

But that's not the only way to hear Lomax's legacy. From Miles Davis in the 1950s to Moby at the turn of the century, and on to the Inside Llewyn Davis soundtrack a little over a year ago, folk, blues, and pop musicians are always riffing on the iconic songs Lomax collected. Jayme Stone's Lomax Project is the most conscious recent example; it celebrates the centennial by recording new versions of songs Alan Lomax (or, in some cases, his father John Lomax) collected in the field. Stone's international and intergenerational cast of musicians includes Bruce Molsky (fiddle, voice), Tim O'Brien (guitar, mandolin, voice, fiddle), Brittany Haas (fiddle), Margaret Glaspy (voice, guitar), Moira Smiley (accordion), Drew Gonsalves (voice), and many others; they're a distinguished crew of both seasoned veterans and fresh faces on the traditional music scene. The album's style is thus a nice mix of the lived-in old-time sound with the edgier feeling of today's scene, which you can really hear in the vocals passed between Glaspy and O'Brien on "Goodbye, Old Paint":

The group's challenge was familiar to anyone in traditional music: interpret source recordings in an interesting way while remaining true to the spirit of the originals. Since Lomax's field recordings from the late 1950s and later are of such good quality, overly faithful renditions rarely match the originals, and Stone's version of "Sheep Sheep Dontcha Know the Road," (the original is here) might fall into this trap. But in most cases, the ensemble adds welcome variety to the sound: on "The Devil's Nine Questions" (original here), a chorus sings the refrain and adds hand-clapping. "Shenandoah" (original here), adds a jazz-influenced instrumental jam that allows Stone's banjo and Haas's fiddle to shine. The moving lyrics of "Before This Time Another Year (original here) are augmented by some beautiful new verses written by O'Brien:

Most importantly, a lot of the pieces they've chosen to record aren't commonly covered. "T-i-m-o-t-h-y," a sweet little ballad about courtship that Lomax recorded in St. Eustatius (original here), is given an engaging setting, as is "Bury Boula For Me," a kalenda learned from calypso singer Neville Marcano (original here). "The Lambs on the Green Hills," a mournful version of the song often known as "The False Bride," was learned from one of the great oddities of Lomax's collection, a session of folksongs sung by Robert Graves, the poet, novelist, and mystical scholar who wrote The White Goddess and I, Claudius. (Graves's recording is here.) By arranging these unusual gems, this work expands our awareness of the collection's scope and variety. More importantly, it places new wonders alongside old favorites, for a listening experience that's fresh and fun no matter how familiar you are with Lomax's collection. Watch the album trailer below!

Another album with Lomax connections is Can't Hold the Wheel by The New Line. "Train on the Island," which opens the disc, was first recorded commercially in 1927 by both J.P. Nestor and Crockett Ward and his Boys. John Lomax recorded Ward and "his boys," Fields Ward and Wade Ward, ten years later; Alan Lomax and his young intern Pete Seeger recorded them again in 1939; and Alan Lomax visited them again, with a CBS radio crew and a photographer in tow, in 1940. He kept visiting the Wards until 1959, when he finally recorded "Train on the Island" (original here). "The Old Churchyard" is a hymn that Lomax was among the first to record (original here). The New Line learned the version by Almeda Riddle, whom Lomax was also among the first to record (session here). Lomax never recorded Riddle's version of this song, but he and his sister Bess Lomax Hawes encouraged my teacher Roger Abrahams to do so. Finally, the very first recording of Lead Belly's classic "Goodnight Irene," which closes the disc, was made by John and Alan Lomax.

The Bog Trotters Band, Galax, Virginia, January 1940. (L-R): Doc Davis, with autoharp; Uncle Alex ("Eck") Dunford with fiddle; Crockett Ward with fiddle; Fields Ward with guitar; Wade Ward with banjo. This photo was taken by a CBS photographer to publicize an "American School of the Air" radio show with Alan Lomax. It's a Library of Congress photo in the public domain.

The New Line's arrangements of these traditional American folksongs (plus a few others) are unusual for integrating the African mbira into an American string-band context. The mbira (a lamellophone often called a "thumb piano") looks deceptively simple but stymies most who try to play it; bandleader Brendan Taaffe, it turns out, is a masterful player who spent time in Zimbabwe learning the technique. The result is that he doesn't stand out in a flashy way, but blends artfully into the ensemble, adding rhythm and harmony. It sounds especially natural with the gourd banjo, which is after all another African import. The idea works remarkably well, giving some great old songs a laid-back vibe with gentle mesmeric depth. If you like old folksongs with unusual acoustic arrangements, this is a treat.

Another Lomax Connection: with his mbira, Brendan Taaffe performs a solo rendition of Texas Gladden's version of "The Devil's Nine Questions," which Lomax recorded in 1959.

Anna & Elizabeth, the duo of Anna Roberts-Gevalt and Elizabeth LaPrelle, has returned with a second CD of (mostly) traditional ballads, hymns, love songs, and fiddle tunes from the Appalachians. Two young women with a lot of projects both together and separately, they're known as a musical duo, as co-hosts of the Floyd Radio Show in Floyd, Virginia, and as two of the foremost "crankie" artists in the country. Musically, LaPrelle's powerful vocal delivery is supported Roberts-Gevalt's gentler and more lyrical sound. Between them they also play banjo, fiddle, and guitar. Their approach can be very traditional, as on hymns like " Long Time Travelin'" and country classics by the Carter Family and the Stanley Brothers. But they also enjoy avant-garde touches, like the discordant droning underlying their harrowing version of "Greenwood Sidey," a song about infanticide and ghost-babies from Hell. Other highlights include the old Scottish ballad "Orfeo," and "Father Neptune," a song by the mysterious Connie Converse. LaPrelle and Roberts-Gevalt give each song and tune what it needs to thrive. When LaPrelle's tight voice sings "God sent to Hezekiah a message from on high," while Roberts-Gevalt's guitar chops along like a train gathering steam, you know you've found the real thing!

What about Lomax? One connection is their rendition of "Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow," which they learned from a 1937 field recording of Kentucky singer Martha Williams made by John Lomax. Another is their whole attitude and approach: by visiting old folks and recording their songs, producing their own art and music, hosting radio, and thinking about what these old songs mean, they're leading a life like Alan Lomax's. By spending time in archives (including Lomax's beloved Library of Congress, where LaPrelle had a fellowship years ago), they're ensuring his work and the work of others like him will remain relevant forever. The names Anna and Elizabeth even have a special resonance: they're also the names of Lomax's daughter and his wife. Thanks to musicians like these two, and the others I've talked about here, Alan Lomax can rest easy and be proud of those he inspired.

(Dicslosure: My day job is in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, which is the home of Lomax's original field recordings. However, these reviews are my personal opinions only. They don't reflect my government role, and don't constitute an endorsement by the Library.)