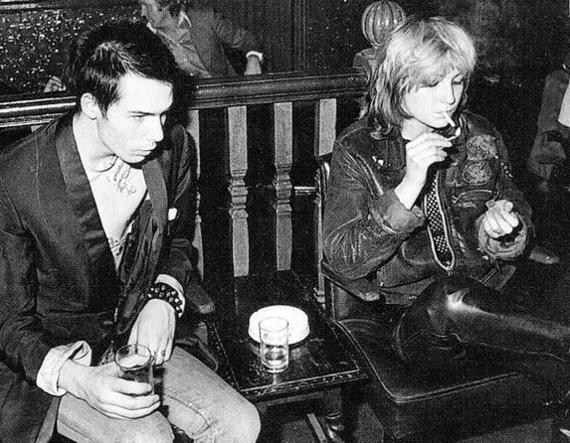

Proto-punk Viv Albertine admits it might have been easier to confess to having a cool and steady rise to stardom, using experimentation and shock tactics as her climbing tools, later to be remembered as one of the primary and resolute shapers of a movement before the movement even got its name. But her story in 'Clothes, Music, Boys' doesn't entirely unfold like this. The time during which her legend develops, alongside friends Mick Jones, Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten, is just one segment of a much bigger life trail of enduring creative, emotional, and physical combats. It's a memoir of Viv Albertine exposed, in a life of perpetual falling and clambering to rise time and again - not just as an artist, but as an person.

Continuing to subvert expectation, she is both punk and pioneer, pushing the boundaries in music and as a woman, but in a world where personal insecurities closely lurk. It is this absolute telling, this straightforward honesty, that is for Albertine the 'worst' taboo. And through distilling the bigger picture of her life story into the pages of her book, she intentionally and unabashedly deconstructs her own legend - making what she calls a "responsible book".

NUDEMOLE: Is it true that you wrote 'Clothes, Music, Boys' to speak to a younger generation of girls?

Viv Albertine: Well I knew women my age who'd been through the music would be interested, but I really wanted to reach a wider audience. The Slits always wanted to reach a wider audience, but no one could really see us back at that time, people were too frightened. So I didn't want ordinary women who hadn't been in a band to be alienated by it - which is why I put the whole second half in.

I think the publishers were dubious because they thought people would just want the punk thing. But I said no. I want this book to be able to be read on a beach, on a plane, in your bedroom, by any age group, male or female. It's a story of a life, not punk rock.

N: So where did the initial spark come from? Because you say at the beginning that anyone who writes an autobiography is either a twat or broke...

VA: I was doing gigs, but not that many people were coming. And I've always been much more interested in the message than the medium, so I don't really mind what medium I work in as long as I'm communicating. It's a whole mixture of things. And I thought maybe a book might resonate more.

N: And to what extent of The Slits being women do you think really affected how successful, spectacular and viable you were in the beginning?

VA: It would have totally affected it at the time. Because when you think, people had never seen a girl on stage, play guitar or drums before, so they seemed shocked. And they'd never seen any girls with our attitude. If someone tried to pull Ari off stage, we'd bash them over the head with our guitars. And our clothes...it was all too much for almost a lot of them to even hear the music.

N: Yeah, didn't you tell Palmolive to put her bra back on under her see-through top because it was distracting from the music?

VA: Yeah [laughs] because we hadn't seen any girls on stage before. We used to have massively long discussions about how we should stand on stage. Should we stand with our legs apart? No, all the guys with guitars in skinny jeans stand with their legs apart, and you'd think, we can't stand like that. We'd spend hours and hours, days and days, discussing how to stand. But I remember I used to like how Keith Levine stood, with the heel of one foot on top of the other foot.

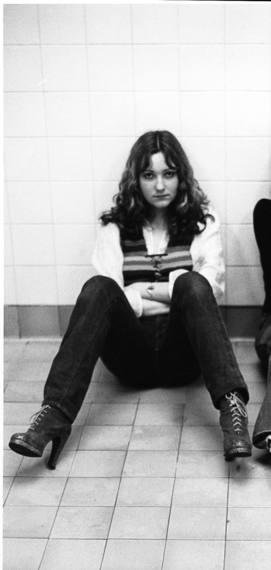

N: So when you began to push boundaries in music with your attitudes, instruments, and clothes, did you feel self-conscious and unsure of yourselves at all, despite being punks?

VA: No, because we were a whole gang. We were excited by it. We knew we were pioneers. And we felt quite responsible to other girls, and future girls. We wanted to be remembered. So we were very careful about our music, what we recorded, what we wrote about, what rhythms we played and whether we played the same rhythms as men. Core structures...every little thing was pulled apart and looked at fresh. What we wrote about, not making our voices all little girly, not with American accents, not to stand with our legs open. It was so exotic. None of the other bands had that. There were bands that came out after us like The Raincoats but they'd already seen us do it. And none of the male bands thought like us - they just all carried on in the rock tradition.

N: And in terms of the clothes - in the book you talk about buying yours from Sex - how much was Vivienne Westwood really an influence on you?

VA: She was a massive influence...as a person, an attitude. I went to Vivienne's shop, cause I met a guy in my art school who worked with her. And for the first time, I'd met a working class woman who was confident, a working class woman who was an artist. There were no role models on TV - there were only two stations. All the announcers were men, anyone in a high position - even doctors and dentists - were men. There was no one...and then there was Vivienne Westwood, who had loads of ideas and looked fantastic.

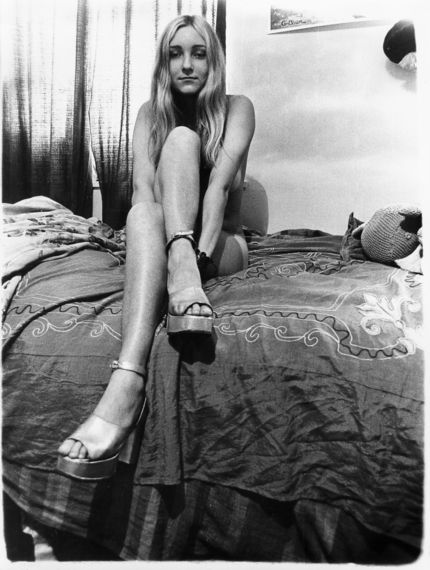

She deconstructed all her clothes, but in a very 'can't be bothered' way; she'd have a whole batch of cheap t-shirt that were shit. She'd just turn them inside out, they were too long, she'd cut the bottoms off, cut the sleeves off, leave it frayed, not be bothered to sew it. Spray words across it. And I saw that attitude towards her clothes, and I thought - not really consciously - that if you can do that with clothes, then you can do that with music. You don't have to be able to play brilliantly, you don't have to be able to finish it all off and know hundreds of chords, and be able to move your hands quickly. You just want to be able to have something to say, an individual voice that hasn't been heard before...which we so haven't got now.

She looked like nothing I'd ever seen before, but it was amazing. And she never looked sexual in the way you'd try to attract men. She might wear a rubber skirt, but it would be a bit dowdy. It was so lovely how she undermined it all. So The Slits did that and more, and we started adding all the signals that you're a girl and a boy, like a tutu or your brownie uniform or your dance tunic, or pretty little handbags or whatever. And we used to mix it up with the sex stuff and boys clothes. So in the end, when we were walking down the street like that with a filthy attitude and black eyes, they hated us. We got attacked and stabbed all the time. And Ari was only 14.

N: So how did you manage to have the nerve to be who you wanted to be, and do what you wanted to do, with that level of threat always looming?

VA: It was totally threatening all of the time, all day. We could never go home on our own at night. You'd more or less have to sleep at someone else's house. We couldn't split up. Consequently we argued because we saw so much of each other. And I was 21 and Ari was 14, so that's a big age difference, but she was so brilliant onstage and musically that it was worth it to me. But, yeah, it was scary walking around, but very important that you lived your politics. People didn't take it in a plastic bag and dress up when you got to someone's house. We were living the everyday fear of it. But on the other hand, if we ever attacked anyone - if someone pulled us off stage - we made them bleed. And no one ever went the police. You were on your own. No one gave a shit about you, because you were just lowly. Even though they didn't treat normal girls nicely, there's a certain veneer of politeness because she's dressed like a girl. And because we weren't, we didn't even get that! So now everything's a bit tame to me.

N: Your hugely influential as a pioneer in music and beyond, but in reading your book - and maybe this is to do with a younger voice you access - you at times sound somewhat self-depricating...

VA: Mmm...

N: But at the same time you're a part of this scene where you're a punk and you're strong...

VA: I know! And people were scared of us. But I thought it was necessary to say that no matter how cool someone looks or how confident, if you're honest, there's insecurity and lack of belief in your ability - especially as a girl back then when no girls were doing it. Now, I think one of the great legacies of punk is that you can be a bit DIY; people understand that you can be not technically able, but still have something to offer.

I think if you're a creative person who is trying to push boundaries, how can you really be confident about it? It's people who are confident that make shit work. It's different if we're making entertainment - great pop songs or if you're a singer like Rihanna and you just go out and you do your entertainment - that's different. You can be confident about that; it's almost a science. But if you're working in areas that haven't really been plundered before very much, or that are embarrassing or revealing, then you've got to be the sort of person who is tentative. And it's painful; I'm such a private person. I've written that book, which is so not private but it's like the work's done separately to the person. I'm not going to write that book - any book - if it's not the best and the most moving book I can make.

N: And in talking of pain in your experiences, you make this very accessible to the reader, don't you?

VA: Yeah, and the thread of the book is how to keep getting up after being knocked down year after year. And sometimes it was a whole 10-year patch at a time I was down, where there was nothing for me. Nothing. I was at the bottom. And I wanted to show that, because when I came back people kept saying, 'Oh, Viv, you're a legend'. But I so wasn't a legend for 30 years and I hadn't really done anything to suddenly become a legend. And there was a time when people didn't really think much of me. So I wanted to really show what was behind a legend because if you don't young people will always think, 'I'm aspiring to be what she is'. And what she is is just a twat like you. And I thought that was important...the deconstruction of a legend. And that's the whole punk ethos: no one's better than anyone else, no one's cleverer; we've all got different things to give. So I wanted to show where I was disloyal, where I was vein, where I was insecure, where I had years of nothing but pain, and I was boring, dull and depressed. Otherwise people just focus on a couple of albums, a book and a film, and that's all they see. And I thought, that's not going to inspire any young women.

N: You talk about survival being one of the motivating factors behind your come-back...

VA: It was an emotional survival after being dead for so long. And to have my husband say, 'Well, if you pick up the guitar, that's it. This seventeen year marriage is over,' I just thought, can I go back to being dead like that? I was pushing a broom around a kitchen every day, driving to school and back, picking up the food. I wasn't brought up to be that. Not that I thought I was brought up to be anything amazing, but I was brought up in very militant times, and mixed with Vivienne [Westwood] and Malcolm [McLaren], who made me more militant. And my mum was quite militant, and one of the first feminists, I suppose. I did it whilst having a young child but I couldn't do it anymore. I wasn't made for that...I'd just come from the wrong background, being that sort of woman. I don't think many women could do that any more, frankly. It's quite a lot to ask of someone - who had been in a band, who had had a child and who had been a stay-at-home mother - to not explore her creativity any more. It just became clear as day to me that I wasn't loved. Because I don't think you could do that to someone you loved. It was a deal for him. And I don't think I've ever quite got over the shock of that, because I thought that was going to last forever, that relationship.

N: And had he just accepted it?...

VA: I probably would have done it for 18 months and then stopped, if it had been acceptable.

N: Really?

VA: Yeah, probably. The fact that he went against me was so reminiscent of punk times when men went against us: the A&R men, or DJs or the writers - they were all against us. And it all felt the same. But coming from the guy inside your house, and inside your head, the person who was most on my side out of everyone - he stood by me all through the cancer and everything...

I think sometimes men find it easier to be a carer than an accessory. I mean, most women I know in bands are pretty lonely. Guys don't want to travel around with you. I know loads of women who do it, but guys don't do it. They're not brought up for it. Still - even thirty years later - it's difficult for a woman to be in a band. I've talked to people like Natasha from Bat for Lashes, or the girls in Warpaint, PJ Harvey...it's difficult. Men aren't brought up to be nurturing like that - to give up their ego to be a supporter. But women still do it. [Whispering] I don't know why?

But it's amazing to come back in my 50s and feel like I can really let go. Look at Kate Bush, Patti Smith, Yoko Ono - three really private people, but when they're on stage or when they're singing they let go like no one else. Look at Patti Smith. The first time we heard her was like listening to someone having sex. We'd never heard a girl having sex and enjoying it.

N: But you were already interested in the possibility of shock, weren't you?

VA: Totally. I was always about inverting, and using erotic art and stuff. And to then come across Vivienne and Malcolm was like I'd come home.

N: And what would you say to those who take the book as something fairly shocking?

VA: There's nothing really shocking in the book, it's all normal stuff. There's hardly any sex in it, there's one drug episode, no orgies, threesomes, S&M, nothing. It's just so straight forward and honest. And I often think that's the worst taboo in way, honesty.

LH: And what does your daughter make of your honesty, and your past?

VA: It's funny, because my husband made me hide everything that I'd done, hide who I was; I couldn't talk about the past, being in a band or show pictures, none of it. So after the divorce I decided, consciously, I'm gonna have to reveal to her who I am because her and I are going to have to be together. And I honestly did wonder whether I might lose her.

She'd just seen me as mum, and so I really took the risk and told her who I was. I stopped trying to be perfect. I had a meltdown a few times about stuff, which probably scared her. But I've no doubt that the love is so much stronger. It's funny to think that you're terrified of losing your kid if you're honest about who you are. There was no judgement from my daughter whatsoever; she's very proud although probably doesn't want me to go on about it too much.

N: So she's read it?

VA: She's read most of it. She doesn't want to see me in too much of a vulnerable light because you need your mum to be strong. You don't want to know all the ins-and-outs...not till she's older.

N: So did you censor certain parts of the book for her?

VA: No, the other way round. I said I want you to read these four or five chapters - the hedonist chapters - because I don't want you hearing them from someone else...an abortion or whatever. Which she did, and she found them quite moving. She was incredibly supportive.

N: And what about the part where you take Heroin? Were you worried about her reading that?

VA: Absolutely. That was the part I was most shameful about. And I made her read it. Worryingly, she said, 'Oh cool, Mum'. It was a terrible thing to do, and the thought of her doing it would kill me. I must say, we were much less informed back then about drugs. My mum wouldn't have known anything in a million years about Heroin. Though I really was aware what would be read by young girls, and I thought I had to contextualise these things and show the consequences. In the end I did think it was a responsible book. Because everything careless I do has a consequence. And I was honest that for that first moment I took it it felt amazing. But then my arm turns black, I feel like I'm throwing away my life. So I hoped I contextualised it all enough to be honest. And I didn't go on to be a heroin addict because of my mum. Sometimes it's some silly thing that pulls you back. And Sid [Vicious], who didn't have anyone in his life (because his mum was an addict, and his dad had run off) went over the edge because there wasn't that one person somewhere who believed in him.

Follow nudemole on Twitter here @nudemole

Visit nudemole magazine