My daughter Maya was three days old, a healthy newborn, when police officers in China's rural Xiaxi Town found her. Or so her adoption papers say. On the 25-kilometer drive to Changzhou's orphanage, the nearest social welfare institute to this farming town, a female officer cradled her. Maya learned this comforting detail when she was 7 years old and at Xiaxi's police station. The scant information in her official documents only hinted at her beginnings: "taken to the Changzhou Children's Welfare Institute by the Police Substation of Xiaxi," our English translation read. So, on a June morning in 2004, the day after Maya and I had been back in her orphanage for the first time, I asked our guide to take us to the police substation.

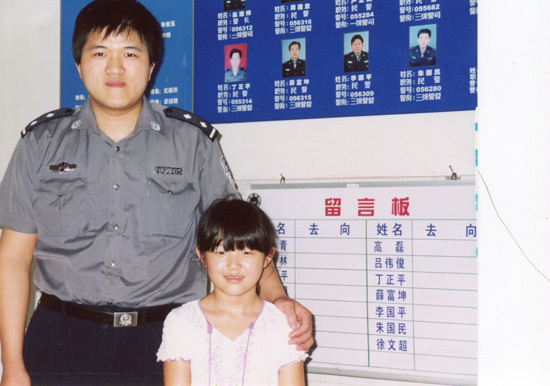

No officer at the station had been on Xiaxi's police force in September 1996, when Maya was abandoned due to China's one-child policy. If they couldn't recall her finding, they'd found other babies since then, so at my request they told us what happened when they did. With Maya standing next to the only female on the force, the officer revealed that the woman officer held the babies on the way to the orphanage. In hearing this, Maya's smile broke through as a rainbow sometimes does after an intense storm passes. Relief washed over her. Yet, to absorb this new reality as it collided with imagined inklings about being left in an unidentified location was exceedingly difficult. She had no questions, Maya told us.

"She's the first to come back," the policeman said, breaking an awkward silence. No other abandoned Xiaxi baby had come back to their station. "Happy and healthy," he declared, his eyes fixed on Maya. His pleased grin conveyed a sentiment in need of no translation.

On our way into Xiaxi, Maya gazed out the window. I could not imagine the emotional stew this policeman's words had stirred inside her. I held her as we sat in silence. I wanted her to know the courage it took to hear what she'd heard, and so I leaned in and softly said, "Maya, you gave them such a magnificent gift. By seeing you happy and healthy you gave them an ending to their tough journey in finding babies. I know they are grateful."

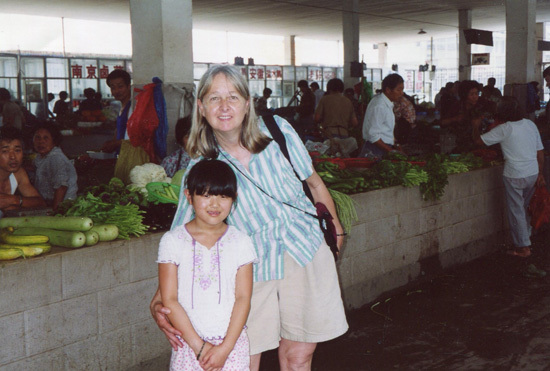

More than anything, I wanted Maya to return to America feeling a positive connection to this country and town she'd come from. Once in Xiaxi, Maya and I went into the outdoor market. Merchants' eyes tracked us, mostly staring at my blonde hair. Foreigners do not show up in Xiaxi. Shoppers reached out to touch Maya and talked at her since she didn't know what they were saying. When she recoiled, they moved away. Why was a Chinese girl clinging to this foreigner? Maya was grasping my hand tightly as we circled the stalls of vegetables, meat and fish. We hurried to our car.

"Back to Changzhou," I told our driver. Our visit to Xiaxi was over. Setting off from Changzhou, I hoped we'd spend the afternoon wandering in Xiaxi Town. Yet, in my daughter's grasp and frightened look she was telling me that I'd made a mistake in bringing her here, especially after all she'd absorbed at the police station.

Back "Home" in Xiaxi, as a Teenager

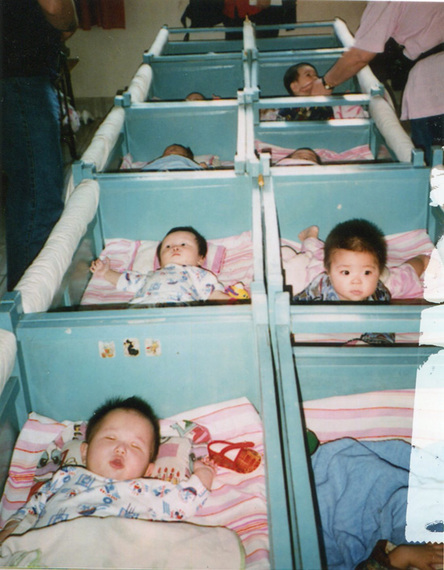

At the age of 16, Maya returned to Xiaxi, and Jennie, her lifelong friend, was with her. The girls were born a week apart, Jennie in a nearby farming town. Police in Xixiashu found her when she was one day old. Or so her adoption papers say. For nine months, the girls lived in neighboring cribs in Changzhou's orphanage.

Maya (front, left), Jennie, (second back, left) in Changzhou orphanage. June 1997. Photo by Melissa Ludtke

In August 2013, Maya and Jennie set out each morning from Changzhou to spend time with girls who'd grown up in these towns where they'd been abandoned. I had hired a bilingual video crew to capture these rare encounters among girls whose lives diverged so dramatically after their births. I sensed that the girls' cross-cultural experiences could illuminate for others how being back in a place of meaning, a place holding clues about a life that might have been, can become a powerful path to self-discovery.

"I felt at home," Jennie wrote, back home in America, "Even though I had no memories of Xixiashu, I finally fit in with the majority. After years of being surrounded by people who do not look like me, I was able to recognize physical features that were similar to mine."

Being with the Chinese "hometown" girls helped Maya frame a sense of her identity:

"So what are you?" the [Chinese] girls asked me. 'You look Chinese on the outside but you are American on the inside.' At first, I detested this description. If the substance of my being is not Chinese, I might as well be white. Once content with describing myself as 'Chinese American,' now I was hit with its vagueness. Where do I belong between being Chinese and becoming American?"

Adolescent adoptees often want to search for their birth family, some of them feeling that only a biological reconnection will buttress them during the challenging years of identity formation. Maya and Jennie did not return in search of their birth families, who had left no traceable clue about who they were. Instead, the "hometown" girls passed on to Maya and Jennie the gift of foundational pieces of self-understanding; after being abandoned as girl babies, now, as teens, they know what happened to some girls whose birth parents kept them. The Americans returned home feeling as though they now belong to a place that had felt so distant from their lives. Maya wrote about her feelings when she returned home:

"For those I met in Xiaxi, family is blood and ancestry. "You do not know your real parents?" strangers would ask me soon after we met, sympathetic and eager to help me find mine. "When is your birthday? What orphanage were you from?" To me, their words "real mother" sit heavy in my mind. Even if I'd spoken their dialect fluently, I am not sure I could have explained. I have a real mother, who raised me and loves me. My biological family might not be whom I romanticized them to be and finding such strangers would not instantly conjure love. Instead, it was in the welcoming care that countless strangers showed me -- in placing watermelon slices in both of my hands, pulling a comb through my hair, and attempting to cool me in 110-degree heat -- that I found home in Xiaxi, and that was enough."

Melissa Ludtke is a veteran national magazine journalist who is producing "Touching Home in China: in search of missing girlhoods," a transmedia iBook chronicling Maya and Jennie's return to their "hometowns" to be published in September 2015. A free download of its pilot chapter is at the iBooks Store. For more information, go to the project's website or check out its Facebook page. This is adapted from an essay published on The Broad Side in September.