Part Three

In the late 1990s, under the guise of corporate "freedom of speech" initiatives, drug companies pressed for the right to advertise their products directly to consumers. For the previous 70 years, the FDA, whose mandate is to protect the public from impure, ineffective, or dangerous drugs or food, believed that pharmaceutical promotions were best filtered through doctors, who were thought to be better judges of the difference between fact and commercial hype.

Nonetheless, drug companies pressed the case of "patient education" and their rights of free speech. Within the U.S. climate of corporate rights, there were legal precedents for allowing direct advertisement to consumers. Shire and Janssen began to lobby for the right to direct-advertise their controlled drugs as well, despite the fact that the U.S. was a signatory to a 1972 UN treaty on narcotics production and international trade that specifically prohibited advertisement to the public of potentially abusable and addictive drugs. (New Zealand is the only other developed country that allows direct-to-consumer drug advertising.)

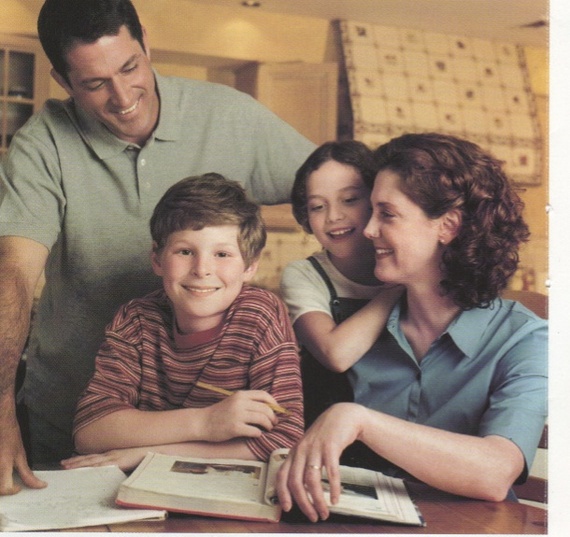

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was concerned about international repercussions but ultimately decided that the trend in legal decisions was so likely to affirm the rights of stimulant makers to advertise to the public that it didn't even try to block the companies. As a result, since 1999, the public has been inundated with a plethora of TV and magazine ads showing smiling "successful" children surrounded by parents and sibs.

A typical headline reads, "Thanks to new ways for effectively managing ADHD, homework may be a more relaxing time at the Wilkin house. Help turn everyday challenges into daily successes." A toll-free telephone number is offered for "the latest treatment information" about ADHD. At the bottom of the page, in very small print, is a statement that the advertisement is sponsored by a drug company. And with ADHD, that company is most likely Shire, makers of Adderall.

Once one company began advertising to the public, all their competitors did so as well. It wasn't long until advertising as part of the cost of drug development rose sharply and was reflected in the cost of the drug itself. In 2005, a full-page ad for Adderall overlaid the cover of People magazine. More recently, Shire paid for 50,000 comic books intended to "educate" children about ADHD and the benefits of treatment, including taking medication. It's hard to say how much this sort of direct-to-the-public advertising has affected consumer demand. I'm certain the companies themselves know, but they clasp this proprietary information tightly against their corporate chests.

Many studies have shown that patients now come to their doctors asking about a specific drug. In most cases, the doctor complies and writes the prescription, even when costs to the consumer and the insurance company are substantially higher. It remains unclear whether or not the public's health has actually improved with drug-company-sponsored "education," or whether the costs of health care have simply increased. These newer drugs not only come with higher price tags, they rarely have substantially greater benefits; sometimes, they have even more side effects than older versions.

"Free" samples given to doctors to distribute to their patients is another time-honored promotional strategy to introduce new products. One might believe a spirit of charity drives companies to give away their new drugs, and I suppose there are situations in which a truly indigent family benefits from these samples. But by far the majority are distributed to private doctors' offices, where the patients are middle class or higher.

Because stimulant drugs for ADHD can potentially be abused, their makers of are not allowed to offer actual samples, but they give doctors' offices vouchers; the patient can then take the voucher to the pharmacy along with the prescription and get the medication free or at a highly-reduced cost (initially, at least). Drug companies know full well that once a patient gets started on a newer, more costly product, he/she is likely to ask the doctor to continue the newer drug. And doctors generally comply.

Unlike most of the other stimulant makers, Shire is really a one-disease company, selling various versions of amphetamine or non-stimulant products. This merchant of legal speed in 2012 earned $1.5 billion for the current top selling stimulant, Vyvanse, $892 million for Adderall XR, and $464 million for Intuniv -- a highly-advertised sedating non-stimulant drug for ADHD (personal communication/Alan Schwarz). The annual market for stimulant prescription drugs in America in 2012 was $9 billion and another approximately $1.1 billion for non-stimulants (personal communication/Alan Schwarz). These numbers seem incredible.

Between 1996, when I wrote my first book, Running on Ritalin, and 2013, methylphenidate production has multiplied six times, to 80,000 kilograms annually. Amphetamine has increased almost 30 times to 65,000 kilograms annually. In 2013, the DEA approved the U.S. production of 175,000 kilograms of legal stimulants, equaling 193 tons, enough for 550 mg. (roughly 27 Adderall 20 mg. tablets) for every American man, woman, and child.

The enormous amount of legal amphetamines used in this country tracks the rate of ADHD diagnoses in children, which has also exploded in the past 15 years. A CDC telephone survey in 2013 reported that 11 percent of American children's parents had been told by a professional that their child had either ADHD or ADD. Dissecting the data further, 19 percent of high school boys had received the diagnosis, and two-thirds reported using medication.

Regional variations reveal even more extreme situations. North Carolina and a number of other southern states report diagnosis rates of 30 percent among high school boys, while rates in the western states tend to be a great deal lower -- roughly 10 percent. These numbers sober even the most committed ADHD/medication advocates. Can one in three boys really have a psychiatric disorder? What does it say about our country that our use of pills has replaced effective non-drug interventions for underperforming or misbehaving children?

This is the critical moral rub. Pills do work for ADHD, at least in the short term. However, after 80 years, there is no long-term evidence that children who take medication do better as adults. Indeed, there are suggestions that the medications make no difference whatsoever in long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, the pills work quickly and efficiently to improve performance and behavior. This is not a paradoxical effect applicable only to those diagnosed with the condition; everyone becomes more methodical and deliberate when taking this drug.

Non-drug interventions for ADHD also work. Behavioral modification techniques practiced by parents and teachers, and special education interventions (especially small-group instruction) are primary and proven therapies. They take longer and clearly cost more than pills, but they prioritize engagement with the child over efficiency.

When presented with the option of either drug or non-drug interventions, parents and teachers generally prefer that the latter be tried first. However, medical and school systems, insurance companies, and drug companies are interested in efficiencies and selling products. Many incentives and disincentives push doctors and patients to use pills as a first-line response instead.