The Sunday Series. A way to share your story, one of tremendous courage, hope, or inspiration. You are a change-maker, a thought-leader, or even a hero. During this time of year as we celebrate our independence, the story from one man who fought to defend our freedom from perhaps the greatest threat the world has ever known.

The Sunday Series: Saving the World

Seventy years removed from living it, the memories for Harvey Brotman are still vivid.

Exactly one year from the day which "will live in infamy," Harvey Brotman and two friends decided it was time to make a move. "I went down with two buddies to enlist," says Harvey because we knew we'd be drafted anyway." What Harvey couldn't know then is he would become part of one of the greatest military invasions in the history of the world.

But first stop for Harvey was Fort Meade, Maryland and then quickly on to Abilene, Texas. Abilene was tough -- sand, desert, and storms. Harvey, now Private Brotman, says, "they would march us into sandstorms...sand hitting us in the face, your food was covered with sand, you had to keep brushing it off. Finally someone came to me and asked if I would like to go to Fort Benning, Georgia. I figured why not, any place is better than here. Then they broke the news, "there's just one thing you'll have to do, jump out of a plane in flight. I said I would do it, just to get out of Texas."

When Harvey got to Fort Benning it wasn't a pretty sight. "A lot of people were laying there with broken arms and broken legs and telling me I would be sorry", says Harvey. "I figured well, I'm here now, I'm stuck. We did a lot of training and they took us out to show us how to pack the parachute. If you were going to jump, you had to have confidence in the chute you packed." Pack, jump, practice. Harvey was now part of the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Benning, the Screaming Eagles. And before he knew it Harvey was being called overseas. Destination: England.

Harvey and the other paratroopers were stationed in Hungerford and practiced, practiced, practiced. "We did a lot of training, a lot of jumping", says Harvey. "We did a jump on a very windy day and we lost about 50 percent of the guys with broken arms and broken legs, but I was OK."

As World War II took a turn, the Allied Forces planned for a massive invasion of France, on the beaches of Normandy. At 12am on June 6th, 1944, Harvey and his fellow paratroopers boarded one of the more than nine-hundred C47s which flew into France, five hours in advance of the ground invasion of D-Day. "At 12:55am we jumped out of the plane, but I landed in the wrong place, there was no one around. I had a clicker I used for identification and if you got a click-click in return you knew someone was nearby. I clicked, but got no response, and it was pitch black, so I stayed in a hedgerow until it got light. Then I saw the 82nd Airborne, I identified myself and told them I was from the 101st and they let me stay with them for four days to battle until I was sent back to my unit."

Private Brotman's primary responsibility in battle was as medic, to aid the wounded. But Harvey couldn't save one of his own. The man who became his best friend in the service was shot and killed on the first day of battle. Harvey says when you're 20-years-old, far from the safety of home and your friend is killed, it's a tough thing to swallow, you can't understand why, or how this is happening. A tough repercussion of one of the toughest days of World War II.

Harvey's group was part of the 502nd Infantry Regiment. That group eventually ended up taking Sainte-Mère-Église" in France and remained there until it was time to head to Holland. Harvey and the other surviving paratroopers would jump into Arnhem, Holland, a strategic location on the banks of the Rhine River. It was during this invasion into Holland that Harvey took a piece of shrapnel in his chest, eventually leading to his being awarded the Purple Heart.

After the success of Allied Forces in Holland, it was onto Bastogne, Belgium, where Harvey and many of the 101st Airborne were in bad shape. "It was the worst", says Harvey. "It was so cold, snow, freezing temperatures, very, very bad. I went and got newspaper to shove into everyone's boots to try and stop the onslaught of frostbite. We were surrounded by Germans and there were no planes to come rescue us because it was always snowing. The Germans wanted us to surrender." But on Christmas Day, (1944), the clouds finally gave way and the bombers moved in and the besieged American forces were relieved by General George Patton's Third Army. "We didn't think we were going to get out of there", says Harvey, "not until Patton showed up."

Harvey did survive WWII and made it through the ranks during those years, going from Private, to Private First Class, to Corporal and then to Staff Sergeant. He says the greatest takeaway from his experience can be summed up in one simple word: life.

"Life is most meaningful", says Harvey. Losing his best friend on the first day of the invasion brought that reality home in a hurry. "I learned a lot about life and there were so many nice people I met in France and England." But it might have been a telegram which meant the most to Harvey and to his mom back home in Baltimore.

Harvey was an only child. His father was killed in a car accident when Harvey was only 10-years-old, so it was just he and his mother living alone until the day he left to join the war. Because Harvey's parachute took him far from the assigned landing spot on D-Day, the military sent a telegram home to his mother, relaying to her that her 20-year-old son was missing in action. It wasn't until Harvey got a 30-day leave and could send another telegram home that his mother knew the real story. He was fine. Ms. Brotman's only child had survived.

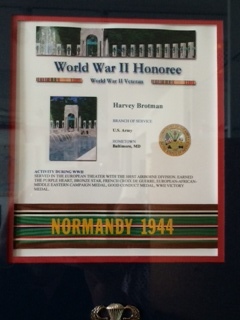

A room in Harvey's apartment is now adorned with pictures and awards from his time in the service. A Purple Heart a Bronze Star, the French Croix De Guerre, the European-African Middle-Eastern Campaign Medal, a Good Conduct Medal, and the WWII Victory Medal. Harvey has saved them all.

And why not. Harvey Brotman helped save the world.

Until next time, thanks for taking the time.

Mark

http://markbrodinsky.com/

Mark Brodinsky, Author, Huffington Post Blogger

The Book: It Takes 2. Surviving Breast Cancer: A Spouse's Story

http://www.spouses-story.com/

Connect with Mark: markbrodinsky@gmail.com