When Joyce Nakamura Okazaki was 7 years old, she was taken to a place in the desert surrounded by barbed wire fencing and patrolled by armed guards. She was told not to approach the fence, she said, or else she would be shot. She, her sister and her parents -- all U.S. citizens -- hadn't committed any crime, much less been tried and convicted. But they were held at the Manzanar War Relocation Center for two years.

When Joyce Nakamura Okazaki was 7 years old, she was taken to a place in the desert surrounded by barbed wire fencing and patrolled by armed guards. She was told not to approach the fence, she said, or else she would be shot. She, her sister and her parents -- all U.S. citizens -- hadn't committed any crime, much less been tried and convicted. But they were held at the Manzanar War Relocation Center for two years.

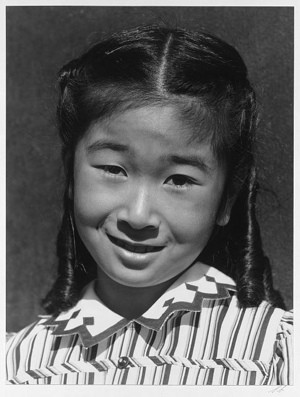

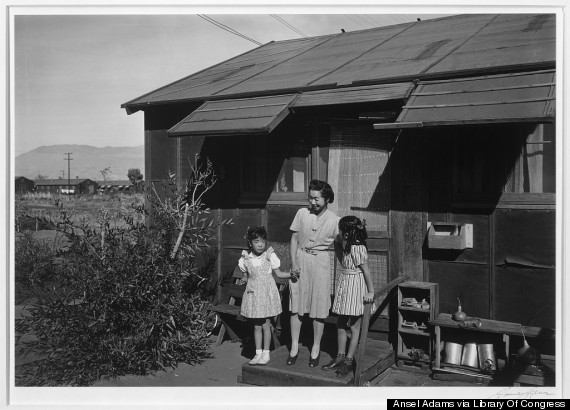

When photographer Ansel Adams visited the camp in 1943, he took several pictures of Joyce, her sister Louise and their mother. When Adams' book about Manzanar was republished in 2001, a picture of Okazaki was chosen for the cover.

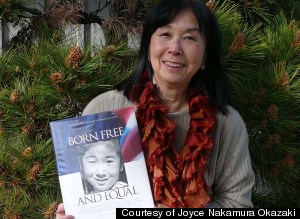

Having her face on the cover, she said, made her feel like she should do something to make sure people know what happened at Manzanar. Okazaki now serves as treasurer for the Manzanar Committee, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness about Japanese-American incarceration during World War II.

She spoke to HuffPost about her memories of the camp and what it was like to be photographed by Ansel Adams. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

How did you find out that your family had to leave home?

I had no idea. I just went with my mother. I don't think they told us, you know, because we were so young. All I know is that we packed up and we went to this area by the railroad tracks close to Union Station in Los Angeles -- we lived in Los Angeles in the Boyle Heights area. We were there and standing and waiting and there were soldiers standing around us with rifles on their shoulders. I asked my mother why we had to stand there but she never replied, never gave me an answer.

We boarded a train that took us to someplace, and we got off, and then we were transported by Army truck to another place, and then we got off and there we were. And later on I found out it was Manzanar, but at the time I didn't know where we were going. It was dark and I was probably a little bit scared because I didn't know where I was. There were ditches all over the place, because they were putting in sewer lines and water lines.

What are some of your most vivid memories of the camp?

One of the first memories was going in and looking at what we had to live in. When we first got there, there was a shortage of barracks -- it was April 2, 1942, and the camp had just opened up a few weeks before, so we got there fairly early but they were bringing in a lot of people. This is all information I got afterward. But I remember the crummy room we had to stay in with these mattresses with straw, and the Army cots that we had to sleep on. There weren't enough cots for all of us. My grandmother and her family were already there, and we had to move in with them.

Then shortly after that, during the day, we had to go for inoculation for typhoid, and I hated being given shots. So we were lined up for getting shots, and I decided I didn't want a shot. I convinced my younger sister to run -- we just ran around the barracks, but they caught us.

People always ask what we did to pass the time. Of course, as a child of 7, I had to leave all my toys and dolls at home, back where we lived. It was all packed away for storage and put away. I couldn't bring my two favorite dolls and that was devastating to me. But mostly we played outside in the sand and the dirt. We played marbles, whatever you played outside, hide and seek, that type of thing. And made do with life. School did not start right away, so I had a rather carefree time until school started in the fall.

What was school like there?

We had a really nice teacher there. The interesting thing about school, one of the first things we learned was to be very aware of the barbed wire fencing. We couldn't go near the barbed wire fence because we were told we would be shot if we even went close to it. There were guard towers all around and they were all manned by sentries. We were also told to be on the lookout for snakes and scorpions. I had no idea what a scorpion looked like. We learned what they looked like by having an art lesson -- we drew a rattlesnake and then a scorpion, and that's how we figured out what they looked like.

What is it like to visit Manzanar now?

I've been back very often because we have an annual pilgrimage [with the Manzanar Committee]. I've been doing this for eight or nine years now. Manzanar is one of the first camps that was developed by the National Park Service into a historical site, and they have a very nice, wonderful interpretive center. The exhibits are really meaningful, and they've got a wall with all the names of people who were imprisoned in the camps. I just have a very good feeling, that this is here for the long term to educate people on what happened, because many people still do not know what has happened. Even just recently I had a college student who wrote to the Manzanar Committee, and she said she had never heard of this in her history lessons. So it's good that it's there, and it's good that it's national and people from all over the country can go and visit it.

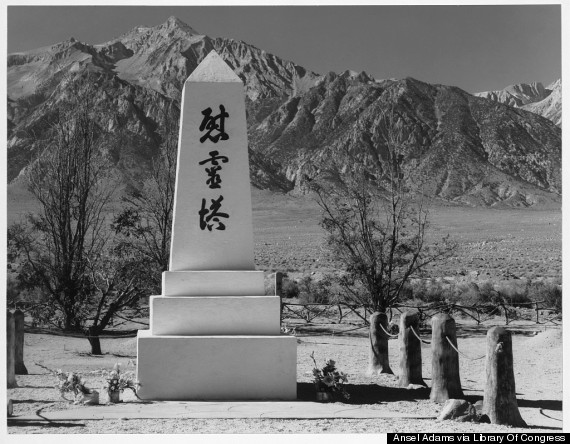

The pilgrimages originally started as a memorial to honor the dead, and ministers of various religions went up there from the time the camp closed, because there are people who are buried at the camp. There's a monument to the dead there -- a large white obelisk.

That's part of it; the other part is to have a program to inform people about our current issues. One of the issues we are stressing right now is getting away from using euphemistic terms to describe what actually happened to us, and I'm a very big supporter of that particular cause.

We don't like the words "evacuation" and "relocation" because evacuation means that people are evacuated because of a danger, like fire or flood. Especially in California, there's a lot of evacuation, and people go back to their homes when everything's OK. Relocation is when you have a hazard such as nuclear waste, and you have to move from that area. We prefer the term "forcibly removed," which is what we were -- we were not allowed to stay in our homes at all, and if we did we were subject to imprisonment because of a public law that was passed by Congress to support Executive Order 9066.

The other words are "internee" and "internment." The meaning of internment is a camp for enemy aliens during a time of war, but we were citizens. Japanese nationals who were arrested were put into separate internment camps that were Department of Justice camps in very isolated locations -- in Montana, New Mexico, Colorado.

And just to be clear, some of these people who were so-called aliens had been residents for a long time in the United States, and most of them did not feel like they were aliens. They were very loyal and patriotic, as my grandfather was -- he was patriotic beyond belief. When he was first able to get his citizenship, he was down there right away to get it.

What were you doing when Ansel Adams took that famous photo? How did he approach you?

Ansel Adams was a little over 40 at that time and not eligible for the draft, and so he contacted his good friend Ralph Merritt, who was director of Manzanar, and asked what he could do. Ralph Merritt asked him to come to Manzanar and take photographs of people living their everyday lives, but he could not photograph the barbed wire fence or the guard towers. I don't know how our family was so fortunate to be selected, but I am glad to this day that I was selected, because it has brought a lot of exposure and joy for me to be in photo exhibits, in art galleries, in museums. But he came to our barracks and he drove with his wood-paneled station wagon, and he came and set up his camera with a great big tripod and the huge camera they had in those days. You had to slide in the film and take it out, and he had this cloth that covers over your head. He took the pictures that way in natural light against the sun, and of course my complaint was, "The sun is hitting my eyes! I can't see!" But he did not say a word and just kept taking pictures. I was always a bit of a mouthy person.

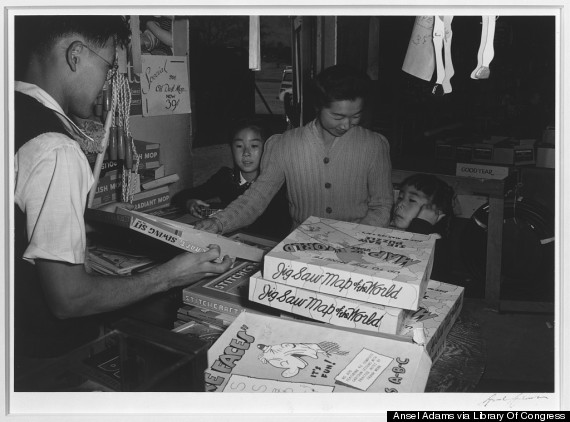

He took our pictures there, my mother and my sister and myself, and then we went on and took pictures in other areas. He took pictures at Merritt Park, which had just been built by one of the prisoners there, and then we took a picture at the store where they sell dresses. We had to pose for that -- we posed for all the pictures. He told us how to hold our head, what to do with our arms, so we did. That, and another picture at a toy loan center that Manzanar had.

What happened to your family after they left the camp?

Since both my parents were college graduates, they were thinking of their future. They wanted to leave camp and they applied for permission to leave. My father was given permission, my mother was denied permission because her father, who was a Japanese national, was arrested and put into a Department of Justice camp. She had to go through additional interrogation and they finally cleared her; she was OK to leave then. Both my parents had to fill out the leave questionnaire -- the other title of this was the "loyalty questionnaire" -- which asks the questions about whether you would serve in the military and forswear allegiance to Japan. My parents answered yes and yes, so they were free to go. My father selected New York, and by the time my mother was given permission to leave, it was already early 1944. My father went to New York and was given $25 and a one-way ticket. He found a job there that took him to Chicago. When school was finished, we moved to Chicago, my mother, my sister and myself, with $25 each and each with a one-way ticket.

How did being in the camps affect people's lives once they got out?

Well the most traumatic thing that affected people's lives was the fact that they had to, in the beginning, give up their homes and their property. If they leased farmland, they lost it. They lost the crops, they lost their belongings, their future -- the future, so important to young people, lost. To middle-aged people. The only people that really didn't care were the teenagers and the old people who were taken care of. When the war ended and the camp was to close, these people that lost everything and didn't have anywhere to go back to -- we've talked to many of these people -- they ended up in trailers or in Buddhist temples or wherever they would house people. Manzanar closed in the fall of 1945, and all those people were taken to Los Angeles and housed in makeshift places. Finally the government put up trailer camps. People, when they talk about it, actually cry because it was so devastating. Eventually they found work -- gardening, housemaid or house boy work, cooks and dishwashers in restaurants, they made do with whatever they could find. Jobs were not very plentiful at the time.

In 1945, even after the war ended and America was victorious, the caucasian population in Los Angeles was extremely hateful and prejudiced against us. They did really hateful things -- I came back to visit Los Angeles in 1946 and my grandmother told me, you have to watch what happens when you walk down the street because these ladies will come up and hit you in the head with their elbow. I think I was about 11 years old then, and I said, well, that's not going to bother me. Well, that's what happened to me. Somebody came and hit me in the head with their elbow, and of course I shouted out and cried, but that person just walked on. I guess it was more of a shock to me than anything.

In 1948, you were able to make a claim for property you'd lost, and they paid about 10 cents to the dollar -- a minuscule amount, really. Many people lost, because they lost the leased land and the ability to farm, and that was a big part of your income. Farming for the Japanese in California was very lucrative. Fishermen were really the ones who lost a lot, because they lost their boats, their fishing gear, and some of that was really valuable, but they lost it all.

What do you want everyone to know about the incarceration of Japanese-Americans?

That we don't want any other group to be denied their civil rights solely because of prejudice, racial hatred, war hysteria or poor leadership, which were the reasons why we were put into camp. We want to make sure that no one ever has to suffer what we had to go through. And believe me, as a child, I probably didn't suffer that much, but there are many 20- and 30- and 40-year-olds who suffered greatly. Of course, many of them are no longer here.

Before You Go