If you're looking for somebody to blame for rising inequality, blame babies. Or, rather, the fact that there soon won't be enough of them.

A drop-off in population growth is a big reason why global economic growth is going to slow down in the decades ahead, French economist Thomas Piketty points out in his new book, Capital in the 21st Century. The top-selling book on Amazon.com is getting a lot of attention for its predictions of soaring wealth concentration and inequality and its call for a massive global tax on the wealthy.

But a key component of Piketty's rising-inequality forecast is a slowdown in economic growth, which theoretically means labor income will slow, too. If returns on investment stay higher than economic growth, as they typically have been, then voilà, you've got a growing gap between the rich (who own all the investments) and the poor (who get paid for their labor).

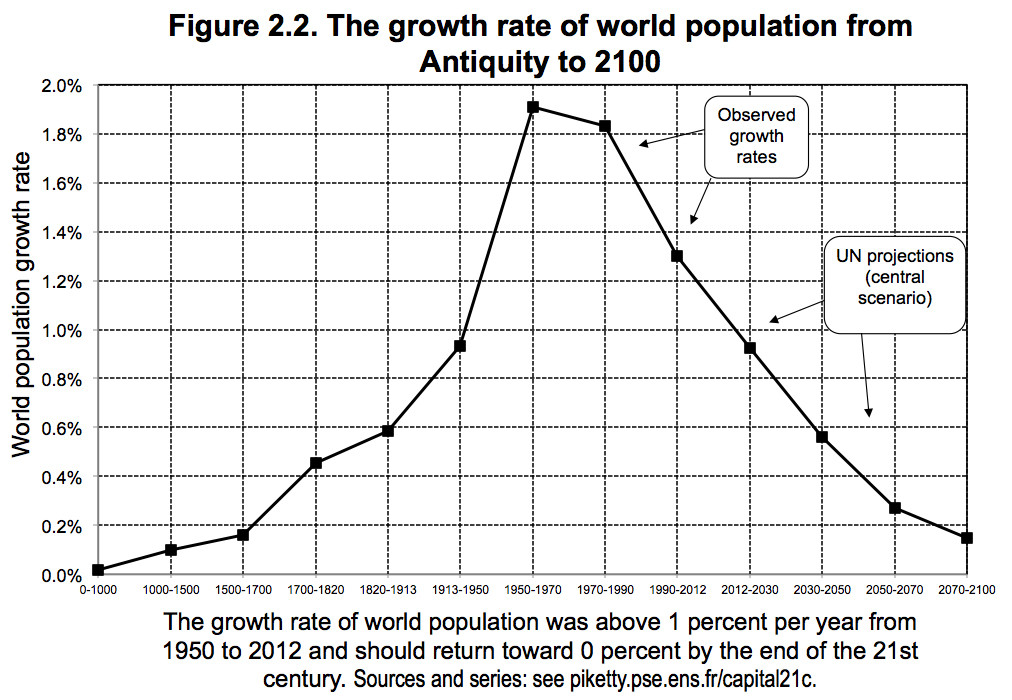

And the slower-growth future Piketty foresees will be at least partially the result of slowing population growth. Typically, population growth drives about half of all economic growth. Here is a very, very long-term chart by Piketty that shows what population growth has done since the birth of Christ, along with forecasts of what it is going to do for the rest of this century:

As you can see from the chart, the world's population grew verrrrry slowly between the year 0 and 1700. And then it absolutely exploded between 1700 and 1970, led first by Europe and the United States and then by Africa and Asia. The Industrial Revolution, improvements in health care and a bunch of other stuff contributed to this growth. But it can't go on forever. Growth rates have already peaked and are starting to fall.

"So what? Who cares?" you might be asking. Slower population growth could mean rising living standards and higher incomes in the very, very long run, as a stable population shares in the spoils of rising economic output, notes Mark Weisbrot of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. A slowdown in population growth is also great news if you're worried about climate change and resource scarcity, as you definitely should be.

The problem is that, historically at least, population growth and economic growth have gone hand-in-hand, with output per person roughly matching population growth. Per-capita output has been a little higher than population growth since the Industrial Revolution, thanks to productivity gains, but not by all that much.

If population growth falls back to the 0.1 percent-per-year rate that prevailed before 1700 -- as many forecasters now expect -- then global economic growth could be well below 1 percent per year, down from about 3 percent in recent decades.

Slower economic growth is not all good news for the wealthy, either, as it could cut their returns on capital and their investment income. But as long as returns on capital stay higher than the economic growth rate, the wealthy will keep pulling ahead of workers.

Meanwhile, middling population growth also makes inherited wealth more important, according to Piketty. When population is growing rapidly, the "old money" is spread thinner. Faster economic growth also means there's more "new money" flying around, which makes old wealth less valuable. In Piketty's view, the reversal of these trends is one reason why, in the next century, "inherited wealth will make a comeback," leaving the 21st century looking a lot like the 18th and 19 centuries.