Emily was 15 when she left her Russian orphanage to join our family and her biological younger sisters. (We had adopted them a year and a half earlier.) The Russian social workers informed us that she had behavioral problems and probably even disorders. They told us that she most likely had Reactive Attachment Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. They said that we shouldn't take her into our home.

But Emily was already "family." Perhaps it takes dizzying intellect to come to that conclusion. Still, I can't see it any other way. When we adopted her younger sisters, they became our daughters. Though we didn't know it at the time, our new additions had siblings. To me, that made us family; and particularly where the older ones had no other family to care for them. To me, the discovery of those two older siblings seemed like an unplanned pregnancy.

For some, the termination of an unplanned pregnancy (and particularly one where there are known challenges, disabilities or "defects") is an option. That wasn't the case in our family. We already had a son with a bonus chromosome (Jack has Down syndrome) and he had taught us that a lower measurement on a paper graph meant nothing when it came to determining how much a family member can contribute to a home.

When it comes to I.Q. testing, my now-23-year-old daughter ranks somewhere in the high sixties. The SB5 classification defines that as "Mildly Impaired or Delayed." To put that in terms for most to understand (and without trying to be offensive) that is about the level that Tom Hanks was trying to portray in the movie, Forest Gump. Emily's lower than average intellect brought additional challenges and one of those was that we had to try to work with her on a level that a much younger child might understand.

After every major breakdown, as we try to put things back together, my daughter cries and cries, saying she doesn't understand why she does what she does.

I have written before about the difficulties that all of us parents of children with RAD have in helping outsiders to understand the anomalies of educating children with that challenge. For me, it is just as difficult helping my daughter to understand. After every major breakdown, as we try to put things back together, my daughter cries and cries, saying she doesn't understand why she does what she does. Recently, that happened, once again.

Of course I have read all of the books. I could have tried to explain to her that the primal part of her brain is trying to protect her from perceived dangers that no longer exist. I could have said that the intellectual part of her brain is beginning to understand cause and effect, but the primal part of her brain is still trying to catch up. I could have talked about immediate gratification versus long term benefits. Emily wouldn't get it.

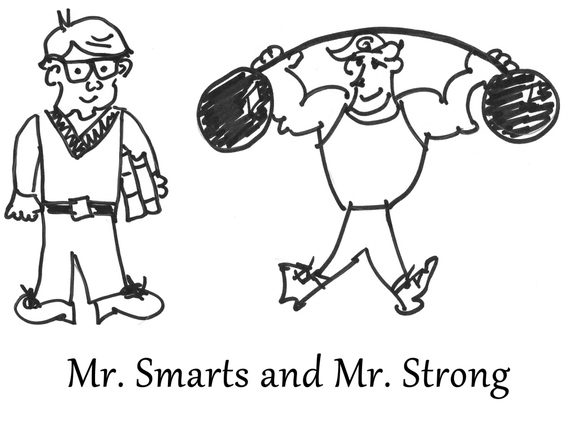

Instead, I drew two cartoon characters to represent two very different parts of her brain. "Mr. Strong," I told her, is the strong part of your brain. His main job is to keep you safe. When he thinks you are in danger, it's his job to keep you safe, no matter what." That led us into talking about "fight or flight." Then we talked about Mr. Smarts. I told her that he's the smart part of the brain. We talked about how Mr. Smarts knows that if you have good behaviors, that you get more privileges. He also understands that most of the things Mr. Strong is afraid of don't happen anymore. Then we talked about how Mr. Strong keeps trying to do Mr. Smart's job, and that Mr. Smarts isn't as strong, so he lets it happen.

Then Emily and I talked about what would happen in a company if the strong people beat up the smart people and none of the decisions were made by smart people. She easily determined that the company couldn't stay in business. She said that the strong people needed to let the smart people do their job.

Emily immediately began to confuse the representation as "smart brain/dumb brain" then "smart brain/bad brain" so it took some effort to help her understand that Mr. Strong and Mr. Smarts were both very important, and that we couldn't survive without both parts of our brain.

She did promise me that from now on, she will let Mr. Smarts be the boss in her brain and that she will make Mr. Strong stick to his own job. It was fun to see her grasp the concept. It was rewarding to see her take that next-first step forward in the three-steps-forward and two-steps-back journey that we travel together. Our progress is quite a dance and we don't move forward at the rate that some fathers and daughters do. Even so, I marvel, as I look back at our beginning, when I realize how far we have come.

Follow John M. Simmons on his blog.