Not all fat cells are created equally. There's squishy, energy-storing white fat under our skin, and then there's brown fat, deeply embedded along the shoulders and back. Brown fat actually burns and consumes the fat stored in white fat cells in order to warm us up.

But not everyone has it. Except for rodents and newborn human babies who have brown fat in spades (to help keep their little bodies warm), most adults have only about 50 grams (less than 2 ounces) of brown fat. People start losing what little brown fat they have left in their 40s and 50s. And obese people, who stand to benefit the most from brown fat's powers, don't seem to have any of it at all, The New York Times reported.

So does obesity cause brown fat to die off, or are people obese because they have no brown fat? Thanks to a pre-clinical trial -- results of which are published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation -- involving mice, researchers are a (baby) step close to figuring out why helpful brown fat seems to disappear in the first place.

Researchers led by Kenneth Walsh, Ph.D., director of the Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute at the Boston University School of Medicine, divided mice into two groups: those that ate "normal chow," and those that ate a diet specially formulated to be high in fat and sugar.

After four weeks on the high-fat, high-sugar diet, the mice's brown fat became dysfunctional and couldn't do its job properly. The fat also experienced a 51 percent reduction in mitochondria, which is the cell machinery in brown fat that breaks down white fat for energy. As a result, the cells had actually "whitened," which means they took on large droplets of lipids -- the fatty acids that make up most of a white fat cell.

In terms of overall health, the mice that ate the high-fat, high-sugar diet were significantly heavier than the mice that ate the normal chow. They were also more resistant to insulin, indicative of pre-diabetes or diabetes.

The researchers hypothesized that the high-fat, high-sugar diet and subsequent obesity had degraded the mice's blood vessels, choking off oxygen supply to the fat cells and thus killing the mitochondria that makes brown fat special.

To confirm their guess, Walsh's team injected the brown fat of the mice that consumed the high-fat, high-sugar diet with the Vegfa gene, known for its ability to promote blood vessel growth. These mice gained back some of their brown fat function, showing that the blood vessels that supply cells with oxygen are key to the healthy functioning of brown fat. Their diabetes also started to retreat, highlighting the importance of brown fat for metabolic health.

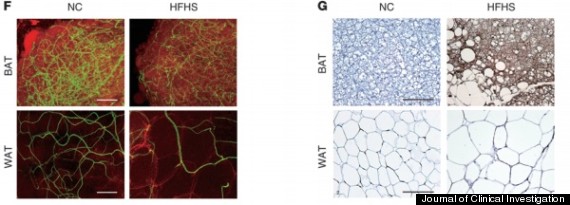

Researchers compared the blood vessels and the fat cells of both the normal chow mice (NC) and the high-fat, high-sugar mice (HFHS). Image F shows that the normal chow mice's blood vessel structure was a denser network than the high-fat, high-sugar mice's in both brown fat (BAT, brown adipose tissue) and white fat (WAT, white adipose tissue).

Image G shows that the high-fat, high-sugar mice's brown fat had taken on a lot of lipids, which made them similar in appearance to white fat.

Of course, the study was a pre-clinical trial that involved mice. Walsh believes that more research is needed to figure out just how important brown fat is to adult humans, considering how little of it we have compared to mice.

Brown fat's potential is enormous. According to brown fat researcher Shingo Kajimura, Ph.D., of the Diabetes Center at the University of California, San Francisco, 50 grams of the stuff can burn energy equal to about 10 pounds of white fat a year. This has research labs all over the world racing to find a way to either increase its supply or try to get white fat to act more like brown fat, which would increase the metabolic rate of obese people.

But finding the answer to this requires a full understanding of brown fat --- including why it seems to die off in the first place. And that's exactly what Walsh's experiment sought to examine.

"We need to understand these processes because we want to get the white adipose tissue to become more functional, to become more brown-like," said Walsh. (Researchers call fat "adipose tissue.") "How will we correct the problem if we don't really understand what the problem is?"

The next step, Walsh explained, is to collaborate with other labs who are doing research on humans and compare notes on the role of the vascular system in brown fat.

"We're looking to see whether obese, diabetic and aging individuals have a reduction in vascularity in their brown adipose tissue," said Walsh. "That seemed to be the trigger that led to the brown adipose tissue degradation in mice."

The takeaway for now, said Walsh, is that people should understand just how intertwined fat and the cardiovascular system are. If you do right by your heart and blood vessels, you'll be supplying your fat cells (both white and brown) with the oxygen they need to function properly. And properly functioning brown fat cells mean that more white fat cells can get burned up for energy, which could help keep you at a healthy weight.

The best way to strengthen the cardiovascular system is -- no surprise -- exercise.

"Exercise is a drug," concluded Walsh. "We know it's good for our cardiovascular system, but this explains why it's also good for our fat, too."