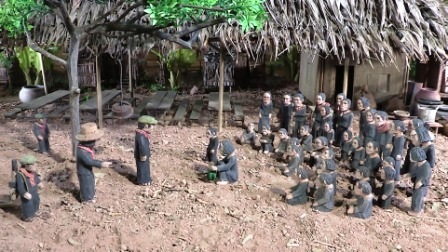

Rithy Panh's award-winning The Missing Picture, about the horrors of his childhood in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, was one of the most powerful films screened at the recent Thessaloniki Documentary Film Festival. Told using clay figurines, the film shows us step by step how the Khmer Rouge took charge in 1975, killing the educated, the "capitalist" class, minorities and those against the regime. The clay figures are suddenly forced to dress all in black, and line up to obey orders, including hard labor in eerily green rice fields, forced propaganda lectures, and the loss of any personal items.

"We were allowed just to have one spoon," said director Rithy Panh to me speaking from Cambodia. "So as not to be individualistic." We watch the members of Rithy Panh's family -- his father and his mother -- starve to death. Throughout, there is a voice-over explaining what is happening to these clay figurines, whose painted eyes reveal intense suffering. One narration is especially unforgettable: about a little girl who slept next to the young Rithy Panh, in her wooden bunk, who was so hungry she moaned all night, chewing on salt. In the morning, she was a cadaver.

Curiously titled The Missing Picture, the film is, however, not only about the genocide of a quarter of Cambodia's population; it is also a meditation of what survivors do with their memory of this horror. "It is for this reason I did not animate the people," explained Rithy Panh. "The people are fixed in time, in the time of memory. They do not move anymore. It is only the narrator that moves." The "missing" picture, Panh continued, is the hole in our memory that each of us has. "It remains a hole unless we speak about it."

It is Panh's use of clay figurines that makes this film enter our own consciousness as a memory we have never experienced. The figures are more than human: Their "soul" speaks through the unmoving clay. "In Cambodia," the director explained. "We believe there is a spirit in everything: trees, rivers. The figurines have a spirit too."

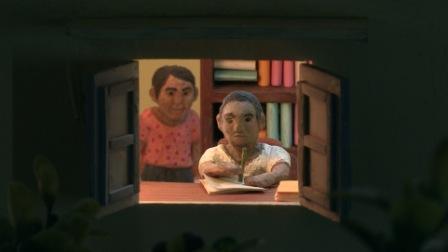

"As children, we did not have toys," he added. "We invented characters and animals; we invented stories." This childlike effect is reproduced in the film. We are in the world of fable, of good and evil: the way a child begins to make sense of the world -- which in this case is a shock. "It is an odd age to be an adolescent," Panh added, speaking about his experience as a thirteen year old during the genocide. "It is when one discovers the world."

Throughout the film, one is struck by the urgency of the director's need to recreate his memory, that horrific world discovered as a child, as well as the family members he lost. "I am lucky to be a film director," Panh commented. "I can create, express. It proves that I am still alive and the Khmer Rouge did not succeed in destroying me. It is like I am reborn, with the death inside of me: the people with whom I have a dialogue. I must live with them."

He continued:

"The Khmer Rouge made mourning impossible. The bodies were treated as objects; the corpses were treated badly. When one kills people in mass, there are no longer rites, no funerals. The identities of individuals are effaced. I try to re-construct these people. Give each a name."

One of the most touching characters "re-created" in the film is the clay figurine who is the director's father. We learn how this educated teacher loved his books -- and found his only freedom under the Khmer Rouge in refusing to eat. Hence the father starved to death before his son's eyes. "It is later that I understood the heroism of his decision," the narrator of the film comments.

The film is powerful in bringing the dead back to life, even though they are now clay.

But a question remains for us: How can we adequately respond to this memory that Panh recreates?

For Panh, the answer is clear. He wants his film to engage the responsibility of the spectator: "Genocide should implicate everyone, because it is a crime against humanity. It is painful that people did not react to the Cambodian genocide. I did not understand how humanity could let these people kill."

But what can a film spectator do about genocide?

Panh's responded with a joyous laugh: "One can do many things in this world. Every day, do small gestures of generosity! It does not mean go to Cambodia. Do it at home. If you do nothing at home, evil becomes normal. Evil has always been here since the world began. Good is what is difficult. It is a work of every day.""

He continued, in a positive spirit: "The world I experienced was a dark world, barbarous, bloody, the worst side of humankind. But it made me the person I am today. It has made me a better human being. It has made me committed to fighting against forms of barbarism, to be generous and open to people."

He is also happy that he is able to give "the missing picture" to the young people of Cambodia, who now see his films and understand the "hole" that nobody wants to speak about.