BEIRUT -- The rockets came in the early morning, shattering both the peace and the buildings as the residents of Moadamiyeh were barely standing up from their prayer rugs.

There were five of them, Qusai Zakarya recalls. He had yet to go to bed, having moved straight from a laptop to a late-night dinner to the fajr, the first of the day's five prayers. As he finally prepared for bed, he heard a distant air raid siren. Then the rockets landed and sarin gas erupted from their warheads.

It was around 4:45 a.m. on Aug. 21, 2013, in a suburb to the southwest of Damascus, the last of several neighborhoods to be struck that morning by chemical weapons. In the days that followed, the attacks would become an international scandal, as the United States accused Syrian President Bashar al-Assad of launching the rockets and prepared for potential military retaliation.

Zakarya himself, a 27-year-old former hotel worker raised in Moadamiyeh, would soon emerge as one of the most powerful voices within the ranks of Syrian media activists, who provided the world with a glimpse into the most devastating acts of the Syrian civil war.

"I wish I had one of him in every major city in Syria," says Bayan Khatib, a member of the Syrian opposition's media office, who helped Zakarya contact journalists worldwide reporting on the war. While other towns suffered as much as Moadamiyeh, she says, none had an advocate as influential as Zakarya, who does not use his given name out of safety concerns for his family.

The rocket strikes marked the start of Zakarya's evolution from just another Syrian nursing grievances against Assad into a tireless public opponent of the regime. He lived through the signature events of the war, from chemical attacks to forced starvation to complicated efforts to halt the violence. And like millions of others, the conflict would eventually force him into exile.

But in that early morning moment, there was only the gas and the feeling of "a knife made of fire just tearing out [his] chest" as he struggled to breathe. When he managed to do so, he screamed for his friends to wake up and make masks for their faces out of dampened rags. They needed to run and get to a high point above the heavy sarin cloud, which would settle close to the ground.

A neighbor arrived, pleading for help for her three unconscious children, and the five men made their move. One ran for his car, hoping to ferry the children to the town's field hospital. The rest left the house and ran out into an apocalyptic scene on the street.

"Everyone is running and falling on the ground, dying and suffocating," Zakarya recalls.

He went after a small teenaged boy lying unconscious in the road with white froth at his mouth. Zakarya attempted a frantic bout of CPR, "punching at his chest" until his friend's old Range Rover, a war trophy taken from a regime officer, pulled up. With the car already packed full of kids, they placed the unconscious boy into the trunk.

As the they pulled up to the hospital, Zakarya fell out of the back of the truck, fainting before he could even hit the ground. He was rushed inside for treatment and then left for dead by doctors after his heart stopped.

Forty-five minutes later, a friend found Zakarya outside of the treatment room, lying on the floor among the bodies of other victims. "He saw me and he went for me and he started crying and shaking me very badly. And I started to vomit this weird white stuff," Zakarya says.

He was alive, but not awake. Only after another 30 minutes and a second round of treatment would he regain consciousness. The first thing he remembers is standing against a nearby wall amid intense shelling and sounds of battle in the weak pre-dawn light. Zakarya spent the next two days shuttling between hospital and battlefield, helping friends from the Free Syrian Army fend off regime soldiers while wearing borrowed pajama pants.

Before the attack, Zakarya had always kept a low profile. He suppressed his desire to become an activist and help spread the word about the horrors taking place in his hometown. Sometimes he would join the town's FSA fighters during emergencies that called for extra men. But with nine siblings and a mother to worry about, he'd mostly kept quiet. He went to the peaceful protests in 2011 that launched the Syrian revolution, but even then he snuck in on his own, avoiding his friends.

But now his family had long since scattered across the Middle East for safety, escaping the shellings and blockades in Moadamiyeh. He had just survived one of the most gruesome moments of the civil war, and had the rare English skills to tell the world what had happened. Now, he felt he had to do more.

THE AFTERMATH

Zakarya didn't have to wait long for a chance to broadcast his story. On Aug. 26, less than a week after the attack, a U.N. investigations team toured Moadamiyeh to inspect the damage and help determine if chemical weapons had been used. In London, BBC radio producer Damian Quinn suggested that his show, "NewsHour," try to get an interview with someone who had accompanied the team.

Quinn laughs as he recalls the skepticism of his bosses. "I remember my editors saying, 'Yeah, well, all right, if you can find that person and they speak English,'" he says. That person was Zakarya, who had shepherded the inspectors through the wreckage during their visit.

Quinn started calling his contacts and eventually got Zakarya's name. As Zakarya remembers it, a friend arrived at around 6 p.m. to take him him to Wasim Ahmad, a member of the town's ad hoc council who was enlisted to track down the English-speaking guide.

When they arrived at Ahmad's house, Quinn was waiting to talk via Skype. It was Zakarya's first media interview and there was no time to prep, but it didn't matter. "It was fantastic," Quinn says. "If he says we were the first interview, then maybe he's just a natural at this."

With Zakarya's language skills in high demand, Quinn asked for his contact details. He knew a reporter at The Daily Telegraph in London who was looking for reliable sources in Syria, he said. Zakarya was willing to talk to him, except for one important detail: He didn't have a phone or his own laptop.

"So Wasim borrowed me his cell phone, he told me that you can use it until you're done," Zakarya says, and then laughs. "I kept it with me for, like, five months."

The call with Quinn set off an avalanche of media requests. After the Telegraph came the Associated Press, Beirut's The Daily Star, The New York Times and other outlets. Zakarya estimates that in the seven months he remained in Moadamiyeh, he spoke to more than 100 journalists on the borrowed Sony smartphone, hopping from house to house to charge it from car batteries that locals used for electricity. He also became a regular guest on Arab news channels like Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera, the two prominent Gulf-based satellite networks.

At first the calls focused on the chemical attack and its aftermath. As the United States debated launching retaliatory strikes against the Assad regime, reporters were eager for information from the scene. Zakarya remembers the mood in the town lifting as American strikes, which would provide relief from the regime, seemed imminent.

"All the people, you will start noticing the kind of smile that they had forgotten about since a long time," he says. "They were just feeling a lot of hope, wishing that this is going to happen."

On the evening of Aug. 31, Zakarya went to the house of his friend Abu Ammar, an FSA fighter. Streaming CNN on Ammar's laptop, they watched President Barack Obama announce that he would seek congressional approval to attack the Syrian regime.

"While I believe I have the authority to carry out this military action without specific congressional authorization, I know that the country will be stronger if we take this course and our actions will be even more effective," Obama said during a speech from the Rose Garden of the White House.

In Moadamiyeh, it was the moment that Zakarya's hopes collapsed. He knew that no attack was coming. "I felt so disappointed," he says. "I learned enough to know that when an American president wants to make a military strike, he just do it without telling anyone. We seen it in Iraq, we seen it in Afghanistan, we seen it in Somalia, we seen it all over the world."

Zakarya had been translating the speech word for word, but he suddenly went silent. Ammar pressed for details, asking what Obama had said. What did he mean by asking Congress? Was he still going to attack?

"I had to lie," Zakarya says. "I told him, 'No, for sure, he wants to do it but he wants to get a cover from the Congress and maybe make the strike even bigger.' And he was happy."

Zakarya was not. He bummed a cigarette and quickly left, only to repeat the charade over and over as people stopped him in the street to ask how the speech had gone. Finally, he found a quiet place, down a side street on the steps of a destroyed building. He sat in the dark and lit the cigarette, cursing Obama as he smoked.

"I sat there for like 30 minutes at least, just thinking and praying that I'm wrong," he says.

Within days, it was clear that he was right. Congress resisted Obama's call for strikes, and Russia stepped in with a plan to have Syria surrender its stockpile to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. The mood in Moadamiyeh reverted back to anger and despair. Locals mocked Obama as "Abu Ali," a nickname for members of Assad's Alawite sect.

As the prospect of international intervention died down, another problem became acute: starvation. By September, the regime had enforced a blockade on Moadamiyeh for nearly a year. At the start, Zakarya says, townspeople had stocks of staples like rice and pasta, supplemented by foraging in nearby woods and in the houses of people who had fled. Now those stocks were long exhausted, and nothing new was coming in.

A standard Moadamiyeh meal in the fall of 2013 consisted of small handfuls of arugula and some olives, chopped up into a meager salad. Sometimes locals would find grape leaves to make into "a weird kind of soup," Zakarya says, "just to have anything in your stomach to keep you going."

He decided to document malnutrition cases in the town, which were growing particularly severe among children. "I started to hear a lot of stories about really weak kids," he says, and he began filming some of them. Five days later, the first of his subjects died.

Forced starvation emerged as one of the Syrian regime's signature tactics in 2013. In cities like Homs and in Damascus suburbs like Moadamiyeh, it laid siege to rebel-controlled areas, hoping to compel their submission through hunger. Hardline rebel groups sometimes copied the tactic as well. Around 250,000 Syrians are currently at risk of starvation, according to the U.N.'s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, and the gruesome stories and photos from besieged towns have led to widespread global condemnation. Yet the use of starvation continues.

To call attention to the dire situation, Zakarya proposed the idea of launching a hunger strike to Bayan Khatib, the opposition media officer who was working with him. "What occurred to me was, I don't know if it's a good idea," she says. "You're already in a fragile situation and all of that. But he insisted on doing it."

On Nov. 26, Zakarya started the strike. "I'm asking all the decent humans all around the world to raise their voices and put some pressure upon their governments to make serious acts to stop this brutal siege," he pleaded in a YouTube video, holding a plate of arugula and olives.

For 33 days he fasted while Khatib and other activists -- who worked separately from the Syrian National Coalition, the opposition's political leadership -- promoted the strike on social media. Zakarya himself wrote blog entries on laptops he borrowed from friends, chronicling hunger, shellings and winter cold. The effort branched out into sympathy strikes that snared some high-profile participants, including Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.), the only Muslim serving in Congress.

"I was honored to fast in solidarity with the Syrian people, who have shown incredible resilience in the face of unbelievable tragedy," Ellison wrote to The WorldPost in an email. "The United States has done a lot to help, but we must do more."

For his part, Zakarya had done enough. Though many areas in Syria were suffering, Khatib believes that Zakarya was responsible for elevating Moadamiyah's case into a major international story. "There were other cities under siege, but I think because we had him there ... the world just knew more about what's going on in Moadamiyeh as opposed to Homs or Dariya or even Yarmouk," she says.

Worried about his well-being, Khatib had filled his inbox with articles about the negative effects of prolonged fasting. He finally gave in and turned his sights elsewhere. On Dec. 28, he ended the hunger strike, citing health reasons. It was time to leave.

THE ENDGAME

On Dec. 12, 2013, people across the Middle East woke up to a snowstorm. In Cairo, it was the first snowfall in 112 years. In Moadamiyeh, it was the beginning of the end.

The town's resistance had weakened during the fall. In Zakarya's telling, after 12 people died in October from malnutrition, more than 4,000 others evacuated following amnesty promises from the regime. Encouraged by that response, the Syrian government sent negotiating parties to Moadamiyeh to secure a truce. Former residents who had previously fled the town returned seven times to Moadamiyeh, asking their neighbors to strike a deal, according to Zakarya.

They proposed a series of steps: raise the regime flag over the town; hand over former military officers who had defected; turn in the FSA's arms; and silence the media, Zakarya above all. In return for each of those concessions, Moadamiyeh would receive food shipments.

"They're asking us to surrender under the name of a truce," Zakarya recalls. Each time, they returned empty-handed.

But the storm, and the bitter cold that accompanied it, eliminated any remaining possibility for resistance. Small patches of plants died, taking away yet another food source. With Assad's forces snowed in, local fighters had pinned their hopes on some kind of attack or intervention that would drive away the soldiers from the notorious 4th Division, an elite formation commanded by Maher al-Assad, the brother of Syria's president. None came.

"We always said no, because we always had faith on other FSA or even in the international community that they will push the Assad regime, one way or another, to have aids coming," Zakarya says. "But after storm Alexa, it just came and went back and nothing happened. And we were done."

On Christmas Day, the regime flag went up above the town's highest water tower. "I cried like a 5-year-old who lost his mom," Zakarya wrote on his blog. Some food, "two small pickup trucks," came in. And the town continued to accede to more of the regime's conditions.

As cooperation increased, Zakarya became angrier with the town's local council. His anger finally boiled over during a live interview on Al Arabiya, during which he resigned from the council and blasted the truce.

"I said that the terms are so suspicious and they're asking us one way or another to become shabiha [regime supporters] working under the authority of an officer," Zakarya says. "After I finished my interview, a friend of mine told me there were some people who went to the security office that we have in Moadamiyeh and asked them to have me arrested for saying what I said."

Zakarya had been feeling uneasy for weeks. Controls on the town lessened after the truce and ahead of peace talks in Geneva in late January. As former residents were allowed back into Moadamiyeh, he saw unfamiliar faces that left him worried about who was around. And the regime had discovered his real name, which he says it used in death threats sent to his phone and placed at the door of his old apartment. Now nowhere felt safe.

THE ESCAPE

Even efforts to sneak out of the country, Zakarya claims, were unsuccessful. The regime called him with details of his plans, telling him he'd be dead if he tried, he says. Finally, there was no avoiding a surrender. He warned his activist friends, shut down his online accounts, and contacted the army.

On a night in early Feburary, Zakarya's friend drove him to central Damascus, escorted by a vehicle from the 4th Division. Less than three miles away from Moadamiyeh, he was stunned to see streetlights burning and couples smoking after-dinner hookah at cafes. "I thought life will be quieter or maybe people will have more sympathy about what's happening with their own people just three minutes away from them," Zakarya says. "I got really disappointed."

He spent four nights in a room at the Dama Rose Hotel in the city center, drowning his thoughts in cigarettes, sodas and episodes of "The Simpsons." He spoke to Khatib, the opposition media officer, on the phone every day, assuring her he was all right.

"My concern is he's going to be in their hands, he's definitely wanted, they know who he is," she recalls. "There was a very good chance that they would either kill him or throw him in jail."

Instead, on his fifth day in Damascus, Zakarya went to the headquarters of the 4th Division with a member of Moadamiyeh's "external committee," a group of former residents helping to negotiate with the regime from within Damascus. The division had launched countless attacks against Moadamiyeh and shelled the town throughout the war.

"A few days before I met them, I was pointing my gun at them and they were pointing their guns at me," Zakarya says. But when he met one of the division's officers, there was no hint of earlier hostilities. He describes the meeting as oddly cordial, perhaps overly so. "The minute we met, he was smiling and I was smiling as well."

The officer, Zakarya says, praised his dedication to the rebel cause and talked about the need to build a shared future between the regime and the opposition. Zakarya believes the invitation was a type of PR stunt on the regime's part, intended "to make me a living proof for their good intentions, let's say. Look what we had and who we didn't kill."

But he also thinks that the officers are genuinely ready for the war to end. Zakarya claims that the soldiers he saw at the 4th Division were small, young and sometimes foreign, a far cry from the brawny, mostly Alawite recruits for whom the division is known. (Experts who spoke to The WorldPost cautioned that there is no way to verify claims about the make-up of the Syrian army, but said that Zakarya's description is possible based on the rate of losses in the Alawite community.)

The visit was over in a few hours, and Zakarya returned to the hotel to stew. "It was a lot of mixed emotions," he says. "I would start with being confused and also feeling disappointed that I had to do it this way ... I was trying to pull myself together."

On Feb. 19, he finally lost his patience. He had dreamed of breaking through the regime's lines with the FSA and driving them out of Damascus, celebrating a final victory over Assad with his friends. But now he just wanted to leave.

"It was a big gamble, but I only thought in my mind that I should live to fight another day," he says. "One way or another."

He won't reveal how he finally left Syria, saying only that the regime turned a blind eye to his escape. The cooperation makes him visibly uncomfortable and even embarrassed. When pressed, he simply replies that "there are some things I will keep to myself."

Now Zakarya is only days away from the United States. He received a visa on Wednesday, and seems stunned, even tense, as he displays it in his passport. He ticks off his mixed emotions: nervousness, confusion, excitement. "Just thinking about a new life," he says, but he's clearly unable to grasp what that could mean.

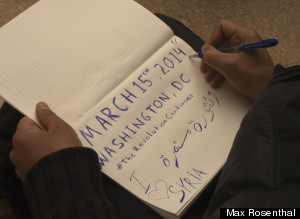

In the short term, it will mean a nationwide tour with the Syrian National Coalition. Plans include a protest in front of the White House on March 15, the third anniversary of the revolution, and appearances before Congress and the United Nations. He jokes about the opportunities he'll have in America: going to both McDonald's and a therapist.

But mostly, he will pick up exactly where he left off.

"I will make a lot of noise," he says. "And I know how to make noise."

This article has been updated to clarify that the hunger strike campaign in November and December 2013 was not carried out in conjunction with the Syrian National Coalition.