When I was a little girl, I adored figure skating. The flawless sparkly outfits, the graceful artistry and athletic technicality of the movements, and most of all, the skaters themselves -- specifically, Nancy Kerrigan.

She was the perfect ice princess with her Vera Wang-designed costumes and her long, ballerina limbs, and she made every double axel and triple lutz she landed look easy. (Plus she had beautiful brown hair and her name was the same as my mother's, which to a girl under the age of 10 -- who also had brown hair -- made all the difference.) She was the symbol of a Cinderella comeback story. In 1994, just weeks before the winter Olympics, Kerrigan was attacked by an unknown assailant who would later be identified as a hitman hired by fellow skater Tonya Harding's husband Jeff Gillooly, and bodyguard Shawn Eckardt. Kerrigan recovered and won the silver medal.

I was not alone in my early-'90s love for Kerrigan. Even before January 6th, 1994, the figure skater's star was quickly rising. After she won a bronze medal at the 1992 Olympics, Kerrigan signed corporate sponsorship deals with companies like Campbell's Soup, Evian, Xerox and Reebok. Her classically feminine image easily secured her a spot as "darling of the U.S. skating community," as journalist Christine Brennan called her in a Jan. 1994 piece for The Washington Post. During the media spectacle that ensued after Kerrigan's attack -- who can forget the iconic video of her crying out "Why?" -- my 7-year-old mind picked up on the media's most basic narrative and took it at face value. Kerrigan was good, Harding was bad. The end.

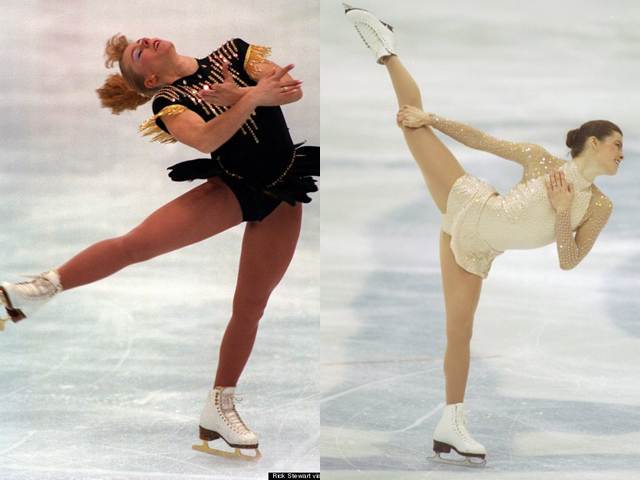

Tonya Harding at the 1992 Olympics, Nancy Kerrigan at the 1994 Olympics.

I never thought to question that story until this week, the 20th anniversary of the attack, when I saw Nanette Burstein's documentary "The Price Of Gold," part of ESPN's 30 for 30 series. Of course, the basic facts of the story remain the same. It seems likely, though it was never proven, that Harding had some sort of knowledge about the attack, and no amount of mitigating circumstances ever excuses violence. However, the film (and Sarah Marshall's fabulous essay in The Believer) paint a picture in which Harding is a far more sympathetic character than the mainstream media would have had us believe. It turns out that frizzy blonde-haired Harding, child of a broken home, who grew up in poverty making her own skating costumes was the skating world's perfect villain.

"The way things were painted was this very black-and-white thing," Burstein told the audience at the Jan. 9 New York premiere of "The Price Of Gold." "[It was] the evil witch vs. the snow queen."

The Tonya Harding-Nancy Kerrigan story played out like a Lifetime movie, and members of both the print and broadcast media ate it up like tabloid candy. It had a catfight element that we love so much, and a class-war theme (even though Kerrigan also came from a working-class family): "The Reigning Ice Princess Taken Down By The White-Trash Wannabe." Connie Chung, who was dispatched to the Olympics on behalf of CBS to cover the story, told the audience at the ESPN film screening that, in her opinion, this story set the pendulum of the news industry swinging in the wrong direction. "The feeding frenzy began to take hold," she said. "It became entertainment. CBS was salivating over this Tonya Harding-Nancy Kerrigan story."

Marshall describes the media's image of Harding thusly and the reluctance of anyone to really question the dominant narrative of Harding's guilt:

She was trash: trash cheats. Trash wants reward without working. Trash is dangerous. Trash doesn't care about other people's dreams. Why question a story that made such easy sense, and provided so much to laugh at along the way?

But quite a few things were lost when we branded Harding as trash and threw her out with it. (She was banned by the U.S. Figure Skating Association for life after she pled guilty to hindering the prosecution in their investigation of the attack against Kerrigan.) Although I remember plenty of discussions about Harding and her bodyguard, I barely remembered hearing about her (by most accounts abusive) husband Jeff -- the one to implicate Harding in planning the attack in the first place, and the one whose version of events was widely-accepted by the American public. We also missed out on a critical examination of the ways in which certain odds were truly stacked against Harding due to her socioeconomic position, her looks and the powerful and athletic nature of her skating.

What I find most fascinating reflecting on the story two decades later -- and the way that my young-girl-self consumed it -- is the way that I so easily absorbed the skating world's definition of being a good woman. From age 7 I knew that I, too, should aim to be graceful, demure, well-dressed, upwardly-mobile, beautiful and feminine; all of the things that the media and the U.S. Skating Association wanted Kerrigan to embody. (Though, even she briefly fell from grace after griping about Oksana Baiul -- proof that no one is shielded from the wrath of the skating world.)

I will always be a Nancy Kerrigan fan, but 20 years later, I can appreciate Harding's talent as well, and I can look at the media frenzy that surrounded these two women with a newly-critical eye.

Harding now lives with her husband and young son in central Oregon. You can hear the deep hurt and bitterness in her voice as she talks to Burstein in "The Price Of Gold" about the fallout she experienced from the scandal and the perceived injustices she experienced. Kerrigan will be a figure-skating analyst for NBC during the 2014 Olympics.

"In all likelihood [Harding] was involved and she obviously has created her own fiction," said Burstein at her film's premiere. "But to never be accepted for who you are in a sport because you couldn't grow out your bangs? I did have empathy for her." Guilty or not, Harding has probably been punished enough.